You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

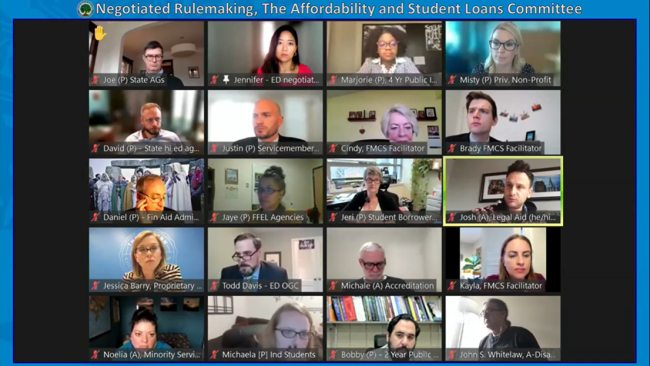

Negotiators meet virtually for the rule making’s final session.

Screenshot/Alexis Gravely

Following a months-long process, negotiators are meeting with the Department of Education this week for the final time to discuss regulatory changes to several federal student aid programs, with hopes of reaching agreement on the new language that officials have proposed.

After meeting twice for weeklong sessions in October and November, the Affordability and Student Loans Committee convened Monday to evaluate how the department incorporated feedback from the first two sessions into draft regulations for 12 issues, including closed-college discharges, income-driven repayment plans and the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program.

The goal of the final session is for the group of negotiators to vote issue by issue on the proposed language and reach consensus, meaning that no member of the negotiating committee dissents. This is a new part of the process—before, negotiators would vote on the entire package of regulations.

“I think it’s easier to withhold consensus when it’s topic by topic,” said Jill Desjean, policy analyst at the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators. “If you’re thinking about the entire package, you have to think long and hard about whether your issue is material enough to blow up the whole thing. Whereas when it’s just individual topics, I think it’s a little bit easier to say no on one thing.”

If consensus is reached, the department will use the regulatory language agreed upon in its Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, the published document of proposed regulations. But by the penultimate day of the third session, it was clear that there were still plenty of unresolved concerns among negotiators.

What are the 12 issues for which the department has proposed regulatory changes?

- Total and permanent disability discharge

- Closed-college discharge

- Eliminate interest capitalization for nonstatutory capitalization events

- Improving the PSLF application process

- PSLF employer eligibility and full-time employment

- Borrower defense to repayment—adjudication process

- Borrower defense to repayment—postadjudication

- Borrower defense to repayment—recovery from institutions

- Predispute arbitration

- Creating a new income-driven repayment plan

- False certification discharge

- Pell Grant eligibility for prison education programs

Have negotiators reached consensus on any of the issues?

So far, negotiators have voted on eight of the 12 issues and have only reached consensus on two: total and permanent disability (TPD) discharge and interest capitalization.

For TPD discharges, the department eliminated the controversial three-year income-monitoring period, when borrowers could lose their discharge if their earnings were above a certain threshold or if they didn’t respond to a request for earnings information during that period.

The department also added language that would allow a borrower’s disability onset date to serve as acceptable documentation for their TPD discharge application if that date is at least five years prior to the application.

“We are extremely pleased by the department’s willingness and enthusiasm to expand the groups of folks who meet the statutory definition and who were excluded previously by basis of not fitting the right Social Security labels,” said John Whitelaw, advocacy director at the Community Legal Aid Society and an alternate negotiator representing individuals with disabilities. “We think of this as a significant improvement in that regard and look forward to working with the department to be creative about how to automate those.”

What if the committee doesn’t reach consensus?

The committee voted on the proposed language for closed-college discharges, false-certification discharges, prison education programs, PSLF and IDR but did not reach consensus on any of those issues. Jessica Barry, president of the Modern College of Design in Kettering, Ohio, and the primary negotiator representing proprietary institutions, didn’t vote in favor of the closed-college discharge language, expressing concerns about the definition of a closed college. The language defines a closed college as one that has stopped providing educational instruction in most—but not all—programs.

Joshua Rovenger, senior attorney at the Legal Aid Society of Cleveland and an alternate negotiator representing legal assistance organizations that aid students, objected to the language for false-certification discharges because it didn’t explicitly state that borrowers have the opportunity to submit a group application that the department is committed to respond to.

“A lot of borrowers don’t know about their right to false cert relief, so that group process is particularly important,” Rovenger said. “What we’ve encountered in the past is that when we have submitted group applications, the department just hasn’t responded to it at all.”

The committee will revisit the issues at the end of the week, if time permits. But if the week ends and consensus isn’t reached on those topics—or on any others that have yet to be voted on—the department is free to write the regulatory language as it sees fit, and it isn’t bound by any of the language agreed upon during negotiations.

What are some of the disagreements?

The department proposed language for a new IDR plan—expanded income-contingent repayment, or EICR—and from the outset, several negotiators were clear that it wasn’t what they were expecting.

“I won’t speak for everybody else, but there was a lot of discontentment with the proposal that we received,” said Persis Yu, former staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center and primary negotiator representing legal assistance organizations that aid students. “We came into these negotiations with a lot of hopes of solving a lot of problems.”

The EICR plan would determine a borrower’s monthly payment amount based on a marginal rate, where a borrower pays nothing for their income that’s less than or equal to 200 percent of the federal poverty level, pays 5 percent of their income that’s between 200 percent and 300 percent of the federal poverty level, and pays 10 percent of their income greater than 300 percent.

“That means if someone earns, say, $60,000 as a single individual, they will pay 5 percent on about $13,600 and then 10 percent on another $21,000,” the department noted. “That means their total payment on this plan is $232, whereas it would be $339 on most IDR plans.”

Similar to other IDR plans, loan forgiveness would be available under the EICR plan after 20 years of repayment. The new plan would only be available for repayment of undergraduate loans.

Among the concerns raised by negotiators were that the 20-year repayment period is too long, loans for graduate programs shouldn’t be excluded and the federal poverty threshold before payments start should be at 300 percent rather than 200 percent.

“The proposal that the department has provided us seems like, frankly, just tinkering around the edges of what we’ve seen before, and there’s a sense that a lot of us don’t want to be here again in a couple of years to renegotiate one more time,” Yu said.

For PSLF, the department proposed language that removes some of the application requirements but explicitly limits which employers qualify to only nonprofit organizations and businesses. Several negotiators argued that PSLF eligibility needs to extend beyond positions within governments and at 501(c)(3) organizations, because lower-income borrowers don’t often have the freedom to choose to work for a nonprofit employer.

The proposed regulations also make changes that would allow more monthly payments to count toward forgiveness, such as by allowing payments on consolidated Direct Loans and under certain forbearances and deferments—including military service, economic hardship and Peace Corps service deferments—to count.

It also includes a new provision that would allow borrowers to get credit for past periods of deferment or forbearance not counted toward payments by making additional payments equal to the amount that they would’ve paid at the time. The department said this is intended to address the issue of “forbearance steering,” where loan servicers have encouraged struggling borrowers to go into forbearance rather than enroll in a more affordable repayment plan.

Joseph Sanders, formerly a student loan ombudsman for the Illinois Attorney General’s Office and negotiator representing state attorneys general, said he doesn’t think the provision fits the spirit of the program, which is about time and not money, and that more needs to be done to address voluntary forbearances.

Negotiators suggested that they would be more receptive to the PSLF language if the IDR language was improved, since they don’t believe either as it is gives lower-income borrowers a reasonable option for repayment.

What happens next?

For the last day of the session, the committee will vote on the three issues related to borrower defense to repayment, which the committee discussed Thursday. They will also discuss and vote on the last issue on their agenda—predispute arbitration. The committee may revisit other issues that they’ve already voted on to try to reach consensus. For example, a representative from the department said Thursday that the group is close to consensus on prison education programs.

In the coming weeks, the department will publish its final proposed regulations, and the public will have an opportunity to comment on them.

And soon, a new committee of negotiators will do the process all over again. The department is establishing a committee to address topics related to institutional and programmatic eligibility, which will meet for its first session in late January.