You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

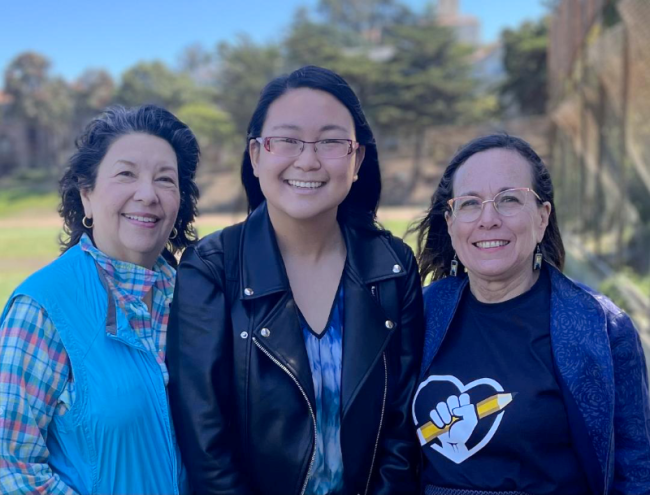

Anita Martinez, Susan Solomon and Vick Chung will soon join the Board of Trustees at City College of San Francisco.

Jess Nguyen

Three new trustees are taking the reins at City College of San Francisco this week and replacing longtime incumbents.

The new group ran as a unified slate during the midterm elections and won with the support of the college’s faculty union after the seven-member board approved unpopular faculty layoffs last spring. Some college employees hope the new board members will end repeated budget cuts and usher in a new trajectory for the college, which has a long-standing public image problem related to budgeting and management. The outgoing incumbents say the faculty cuts were necessary to achieve financial solvency but cost them the election.

New to the board are Anita Martinez, former head of the American Federation of Teachers 2121, the faculty union; Susan Solomon, former leader of the San Francisco Unified School District teachers’ union; and Vick Chung, former City College student trustee. They were endorsed by the San Francisco Democratic Party and the San Francisco Labor Council, among other supporters. They replaced trustees Brigitte Davila, John Rizzo and Thea Selby.

“I think we see ourselves as stewards that have been elected by the community to represent what the voters want. When the voters chose us … that was a powerful message to the people who were expected to win,” Martinez said.

Selby worries the new trustees will focus too heavily on union interests over the broader needs of the institution, including its financial wellbeing.

“I fear for the college,” Selby said.

Meanwhile, San Francisco voters indicated they don’t want to shoulder more financial responsibility for the institution. They sank Proposition O, a parcel tax proposed on the ballot, which was expected to raise about $37 million annually for the college.

Alan Wong, a trustee since 2020 who will remain on the board, said voters’ simultaneous rejections of the incumbent board members and the proposition felt like a sharp critique of the status quo.

“I think that this shows that they do not approve of the performance of City College, and they’re looking for a change in direction,” Wong said.

A New Path

City College has a reputation as the politically beloved, geographically important problem child of the California Community Colleges system. Total enrollment plummeted by nearly 36 percent, from 83,718 students in the 2010–11 academic year to 53,601 students in 2019–20, according to data from the college. City College enrolled only 26,602 students in credit-bearing courses in the 2020–21 academic year. The college is also known for having perennial money problems, conflict between faculty union leaders and administrators, and a revolving door of senior leaders.

The layoffs of 38 full-time faculty members last May—plus cuts to adjuncts, staff and administrators—proved divisive. Some instructors were arrested for camping out on campus in protest of the job cuts and claimed trustees misrepresented financial challenges faced by the college. The incident prompted the candidacies of the new trustees, who promised on the campaign trail to rehire fired instructors.

“The layoffs in the spring just seemed so wrong and so not student-centered and not friendly to people doing the work,” Solomon said.

Selby said the decision was the “death knell” for their re-election.

“It was devastating to cut full-time teachers,” she said. “But we had to do that to balance the budget and to move forward. To me, there was not another way out.”

Selby believes the proposed parcel tax didn’t help their cause, because the proposition, suggested by union leaders, ran counter to the incumbents’ campaign message that City College is financially back on track. After repeated deficits, the college is no longer in debt, and the bond-rating firm Moody’s recently upgraded the institution’s financial outlook from “negative” to “stable.” The college now holds an A1 bond rating, suggesting a low credit risk.

“Our message was we balanced the budget … The school is moving forward … We fixed it,” she said.

The new trustees are taking over at a pivotal moment for the college as it prepares for the accreditation renewal process, which culminates next year. The Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, its regional accreditor, asked the college in 2012 to prove why it should remain accredited and gave administrators a deadline to correct a series of financial and administrative problems, some of which were identified as far back as 2006. After five years in limbo status, and policy changes at ACCJC, the college was granted accreditation for seven years in 2017.

The new trustees are confident the college will be reaccredited, and they have big plans for the coming term.

One goal is to reverse past downsizing efforts. Solomon said there are currently courses that don’t have enough sections to meet student demand, so the college can afford to hire more instructors.

“The potential is there to have more students,” she said. “And more students generates more revenue.”

Martinez sees noncredit programs, such as English as a second language, as pipelines to degree programs and believes re-expanding these offerings could increase enrollment at a time when the local high school–age population is dwindling. The group also hopes to raise awareness about Free City, the institution’s free tuition program for San Francisco residents, which briefly boosted enrollment when it started in 2017.

The new trustees are eager to “take a larger statewide role” as well, Martinez said. For example, they are concerned about the new state funding formula set to take effect in 2025, which is based on the number of full-time-equivalent students and various student success metrics. Chung described the formula as particularly “punitive” to colleges that enroll high numbers of low-income students and students of color with work and family responsibilities who may struggle to graduate or transfer in a given year.

Martinez recognizes policy advocacy is a less traditional role for trustees. But “we share concerns with a large number of people about the changes that are coming from Sacramento,” she said.

Rick Baum, a longtime part-time instructor at City College, said he’s “very hopeful” about the new trustees, but he’s concerned they will be outvoted because they don’t make up a majority.

“I think they’re confident that they can win people over,” he said.

“Part of being on a board means doing our best to work with each other,” Solomon said. “That is not to say that I expect that we’re going to all have unanimous votes. That’s not how democracy typically works. But we’re going in understanding that everybody believes in City College.”

Aliya Chisti, a trustee since 2020, said she has an “open mind, open heart to the new trustees” and thinks they’ll bring valuable perspectives.

“I really hope there aren’t factions on the board” and decisions are reached “based on discussions that we’ve had with different constituent groups and our understanding of the data, our understanding of all of the facts,” she said.

Fears and Hopes

Selby worries the new trustees’ plans go beyond the scope of their position, putting accreditation at risk. She believes rehiring laid-off instructors is outside their purview and could also reverse the college’s newfound financial health.

She cited a financial review by the state’s Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team in April 2021, prior to the layoffs, which concluded the institution had “excess staffing, excess learning sites, and lack of internal controls” and could “no longer fulfill its commitments to its staff, faculty, administration and, most important, its students while also remaining solvent.” The college was also placed on “enhanced monitoring” by ACCJC in 2020, and again in 2021, because of insufficient funds on hand and over 90 percent of expenses going to salaries and benefits.

“It’s really about the survival of City College,” Selby said.

Rizzo agreed the college can’t afford to pay all of the salaries previously on the books.

“There’s no fat to trim anymore,” he said. “They would have to cut things we’re required to spend for accreditation, like updating computers or building maintenance … They’d have to cut into the flesh.”

“This new board represents a very challenging period,” he added. “I hope they can get through it.”

Barbara Gitenstein, senior vice president for consulting at the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, said boards with remaining and new members have to learn to work together as a “unit,” and the transition isn’t always easy. She noted that board turnover has an outsize impact at public colleges, where boards tend to be smaller compared to those at private institutions, and just a few new trustees can cause a culture shift.

“It’s a good thing when new people come to a board,” she said. “It’s good to get a different perspective. But in the end, they have to function as a whole … There will be disagreements; there shouldn’t be warfare …”

Wong expects the new trustees to be more critical of the administration and suspects this will shift board dynamics. He hopes to be a “bridge builder” between the new and remaining trustees and focus on stemming enrollment declines, enacting new budgeting practices to keep the college financially healthy and ensuring “labor peace” in upcoming collective bargaining negotiations with faculty members.

Martinez said it’s going to take time for the new board members to make their mark.

The group’s election was “a setting of high expectations about what we as a team can bring, how quickly we can bring that change to the institution,” she said. “There are a lot of things to do, but if your house is very dirty, the best way to start cleaning is to start in one corner and work your way out.”