You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

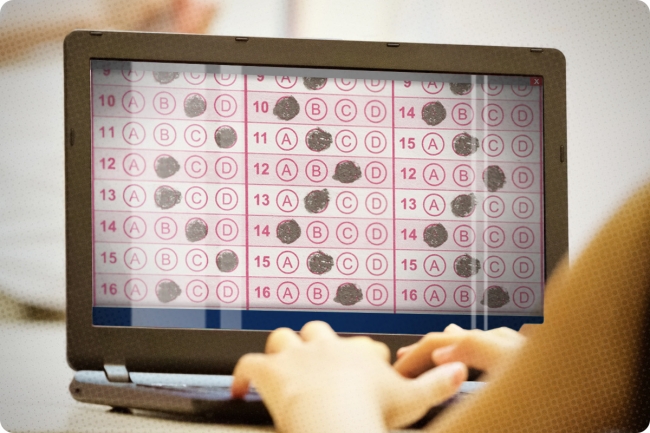

The College Board officially launched its new digital SAT Monday, along with a host of other changes to the exam.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Aslan Alphan and Izusek/Getty Images

Students can say goodbye to those No. 2 pencils, portable sharpeners and big pink erasers; they no longer need to worry about having legible handwriting or fully shading the answer bubbles. The SAT is now completely digital.

On Monday high schoolers began taking the test exclusively on laptops and tablets via a new app called BlueBook, named after the once-universal booklets in which test takers answered essay questions. The digital exam is about an hour shorter than the traditional SAT and features a host of other changes, big and small. Students do not have the option to take it on paper unless they’re granted an accessibility exemption.

The College Board, the nonprofit that owns and designs the SAT, announced the change at the start of 2022, after the COVID-19 pandemic scuttled in-person testing and prompted the vast majority of colleges to waive standardized test requirements. Its implementation this week comes at a pivotal moment for admissions, as colleges across the country consider whether to keep their temporary test-optional policies or return to requiring scores.

Priscilla Rodriguez, the College Board’s vice president for college readiness assessments, told Inside Higher Ed that the organization had been talking about a possible pivot to digital since before the pandemic. When the vast majority of colleges switched to test-optional policies, sending the number of test takers plummeting, College Board leaders knew they had to adapt to a changing world.

“When we made this decision [to go digital] during COVID, we had already entered a new test-optional world,” Rodriguez said. “That actually galvanized us to do this. We thought, ‘If the test is going to be optional, we want it to be the best option.’”

The digital SAT has been available as a pilot for international applicants to U.S. institutions since the start of 2023, and a digital PSAT using the same infrastructure became available to high schoolers last fall. Rodriguez said the feedback from the first round of test takers was “overwhelmingly positive.”

But some critics of standardized testing see the shift to digital in a different light: as a way to maintain the SAT’s hold over the admissions landscape after the pandemic ushered in a wave of test-optional policies, most of which are still in place.

“To me it’s a question of, how does the College Board continue to make itself relevant in today’s world?” said Mary Churchill, director of Boston University’s higher education administration program and a blogger for Inside Higher Ed. “I don’t see a big return to requiring tests or to students taking the SAT in the numbers they used to. I actually think more colleges will go completely test blind … so they’re trying to make the test more accessible and less painful for students to take so that they’re less likely to abandon it entirely.”

What’s New

The major changes to the test, of course, are its format and truncated length. It’s not the only test to get shorter in recent years: the Graduate Record Examination was cut in half last spring.

Rodriguez said the changes are meant to make today’s generation of high schoolers—digital natives who came of age during the pandemic and often have trouble focusing for long periods—more comfortable with the SAT.

The new version includes content changes as well. Instead of nine long reading passages, each with its own group of comprehension questions, the digital SAT features 54 short passages with one response question each. And the math section will now feature a built-in digital calculator, meaning students can leave their Texas Instruments devices at home.

Yoon Choi, CEO of CollegeSpring, a nonprofit that provides free in-school test prep to low-income, first-generation high schoolers, said the students she works with are excited about those changes—especially the shorter length.

“Our students are far behind the national average in terms of grades and preparation, so they’re often very anxious about the SAT, and a shorter test is welcome,” she said. “And I think the changes to the reading and writing section are a great improvement.”

The SAT will also now use adaptive technology to tailor the second half of each section according to a student’s performance on the first half. If a student does well on the first part of the math or reading and writing section, the digital system will ensure they receive a slightly more difficult mix of questions on the next part; if they do poorly, they will encounter a slightly easier second half.

Colleges will not have access to data on which students were routed in each direction—in fact, Rodriguez said, students won’t know, either—but it will be reflected in their scores. A student who gets an easier second half will still be able to score highly, but there will be a ceiling: a perfect 800 on the section will be unattainable. Students who meet the threshold for a more difficult part two will be able to score higher, with a floor of 200 for the section. (As with the old version, the highest possible SAT score is 800 each on the math and reading/writing sections, for a total of 1600.)

Rodriguez said the adaptability function serves two purposes: to enable a shorter, more efficient digital test by eliminating certain questions for students depending on their ability and to improve the test-taking experience for each student.

“We know enough about the student after they’re done with the first half to save them some time,” she said. “This way they’re not bored out of their mind doing an extra 10 easy questions, nor are they feeling incredibly discouraged with another 10 super-hard ones.”

Rodriguez added that despite the shorter length, the adaptive nature of the digital SAT means students should have about 60 percent more time per question. She hopes this will help them feel less rushed and perhaps give them more time to go back over their responses.

Some testing experts and industry insiders see that added flexibility as a good thing and believe the test’s digitization has been a long time coming.

“It’s one of the most exciting developments in the testing industry in a long while,” said Michael Nettles, a veteran psychometrist who until last year served as chair of policy evaluation and research at Educational Testing Services, the company that administers the SAT. “At the same time, it feels inevitable … Conversations about moving away from pen and paper have been happening for over a decade.”

Critics of the move to digital say personalizing even a small portion of the test is anathema to the College Board’s claim that SAT scores offer a standard, meritocratic metric. Akil Bello, senior director of advocacy and advancement at FairTest and an outspoken critic of standardized testing, sees it as an olive branch to those who maintain that the SAT is inaccessible and racially and economically biased toward white, wealthy students.

“This iteration, like every iteration of the SAT, just proves how farcical its claims are,” he said.

Rodriguez noted that going digital also allows for more flexibility in test administration, which she hopes will take some stress off high school officials. Because they no longer need physical test materials delivered to them, high schools can choose to administer the SAT on any weekday over the course of March and April instead of following the previous calendar of dates preset by the College Board. Starting on March 9, the board will also hold SAT weekends with proctored testing locations.

Rodriguez said the College Board can’t account for all potential technical problems that might impede students’ SAT experience, but officials are preparing as much as they can. The organization is offering to lend devices to underresourced high schools and provide broadband support for regions with weak internet access.

A Cynical ‘Marketing Machine’?

Bello said the digital redesign is a cynical ploy intended for one purpose only: to make standardized testing essential again in the eyes of a student population that came to rely on it less and less during the pandemic.

“The College Board is, essentially, a marketing machine designed to sell tests,” he said. “That’s what the digital SAT is: a marketing tactic.”

He added that the significant changes made to the main test ought to affect the long-term testing policy decisions that institutions like Yale and Dartmouth are making, but that has not been a prominent part of the conversation.

“This should complicate those calculations quite a bit,” he said.

So what does the future look like? Nettles believes it will feature “on-demand testing,” the ability to securely and reliably take the SAT from one’s bedroom or local library, ideally much more cheaply and quickly.

Bello and Churchill wouldn’t bet money on that vision. They believe the digital SAT is a harbinger of much greater change, a transitional stage between the testing-saturated pre-pandemic admissions landscape and one that is emerging now: where the SAT and its ilk are taken only by students aspiring to the most selective—and expensive—institutions.

“This is a real moment of transition in the college admissions world, and the digital SAT is kind of like a hybrid car,” Churchill said. “It’s a temporary solution, a bridge between the past and the future. It itself is not the future.”