You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

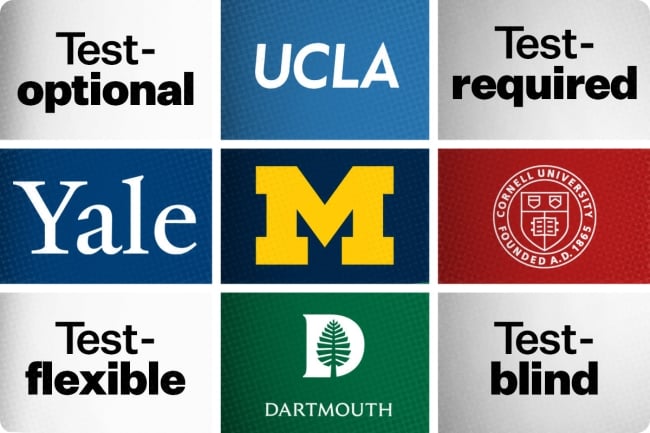

The University of Michigan officially went test optional last week while Yale went “test flexible,” adding to a complicated patchwork of post-pandemic admissions policies.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images | Rawpixel

Last Thursday two highly selective institutions landed on opposite sides of the standardized testing debate.

The University of Michigan formally adopted a test-optional policy, four years after resisting the test-optional wave in 2020 and instead allowing alternatives to the SAT and ACT. Meanwhile, Yale University, which had operated with a temporary test-optional policy during the pandemic, adopted its own test-flexible policy.

The swap illuminates the complicated patchwork of disparate policies emerging as colleges reassess their pandemic-era testing strategies amid intensifying debates over the purpose and usefulness of standardized exams.

Akil Bello, senior director of advocacy and advancement at FairTest and an outspoken critic of standardized testing, said he was pleasantly surprised by Michigan’s decision, considering its equivocation on test-optional policies at the start of the pandemic.

“It’s one of the institutions I really expected to go back,” he said. “That they didn’t tells me there’s a lot of evidence that test-optional is really here to stay.”

Even more striking is that both Yale and Michigan supported their divergent decisions with the same data-based rationale: that the move would help increase accessibility and diversity in the admissions process.

Michael Bastedo, an education professor at Michigan and founding director of the Michigan Admissions Collaboratory, a group of researchers and professionals interrogating higher ed admissions practices, served on the research committee that recommended the university switch to test-optional. He said they came to that conclusion for a few reasons: the policy proved to be incredibly popular with students and families; admissions officers were moving away from heavily weighted metrics like scores and toward more holistic application readings; and most families were confused by the test-flexible policy.

That last point is why Bastedo was surprised to see Yale adopt the test-flexible option. To be sure, there are some notable differences between the two institutions’ policies: Yale will only accept AP and IB scores in lieu of the ACT or SAT, whereas Michigan accepted a broad range of other tests, including the PSAT. In addition, Yale will require a score while Michigan allowed applicants to submit without them.

Still, Yale’s solution is remarkably similar to what Bastedo came to view as a failed experiment at Michigan.

“Just tracking what I saw in discussion among counselors on social media and feedback from families, most thought it was overly confusing,” he said. “It gave students another thing to have to think about and made Michigan an outlier. So it makes me worry about the level of complexity increasing.”

A Policy Smorgasbord

There’s been no shortage of high-profile media coverage touting a return to testing and the resurgence of the SAT; before Yale, Dartmouth College made national headlines last month when it became the first Ivy League institution to reinstate score requirements. Bastedo said he worries that such attention is distorting public understanding of colleges’ testing policies post-pandemic.

“Every school that’s requiring tests now is getting these huge headlines, and I think that’s missing the forest for the trees,” he said.

But that forest is not an overwhelmingly test-optional landscape, either. Among the colleges that have decided on a long-term testing policy, officials have come to a range of conclusions about the benefits and drawbacks of standardized tests.

Even within the Ivy League there is no consensus on the testing question. Last year, before Dartmouth restored test requirements, Columbia announced it would become test-optional indefinitely, and Yale’s test-flexible decision last week added one more variant to the pool.

Bastedo believes the wide variation will make the application process even more challenging for students and families to navigate.

“If you apply to five schools and they all have different testing policies, that makes things harder for families,” Bastedo said. “It adds another layer of complexity onto an admissions landscape that’s already incredibly difficult to navigate, at a time when, in many ways, we’re trying to make the system less complicated.”

David Deming, a Harvard economist and researcher at Opportunity Insights whose work often focuses on standardized testing, said he supports a return to testing requirements. “Why would you throw away a valuable piece of information?” he asked.

But he’s worried that institutions are making concessions and carve-outs where directness and uniformity would better serve both students and admissions offices. Even the notion of going test-optional, as opposed to ignoring test scores altogether, is an unnecessary equivocation, he said.

“I think many colleges are gravitating toward test-optional because they know test-blind would be unpalatable. But if you ask me, going test-blind is better,” he said. “Test-optional is the worst option. It’s trying to have your cake and eat it, too.”

Deming said there are plenty of good reasons to require scores as long as they’re put in context, even though success on standardized tests skews in favor of wealthy students—a fact his own research has helped confirm. And he sees a number of negative incentives pushing some colleges toward test-optional policies, including public opinion that testing is racist (a claim he firmly disputes) and the application-boosting effects of eschewing test requirements, which can lead to lower acceptance rates and higher rankings.

“I don’t necessarily blame the colleges. We’re all in the same ratings rat race. But there are a number of bad incentives here,” he said. “It’s an untenable situation.”

The University of Michigan formally switched to a test-optional policy on Thursday.

Courtesy of the University of Michigan.

Despite advocating for test-optional policies, Bastedo said he never bought the notion that pandemic-era test-optional policies would lead to the demise of standardized testing.

“I think when the pandemic pushed everyone to drop requirements, some people had blinders on,” he said. “They wanted to believe we were entering a world where mandatory testing was a thing of the past. But that clearly isn’t the case.”

Fungible Data

Michigan’s test-optional decision was based in part on research that Bastedo said showed the policy would improve access and diversity at the institution. Yale and Dartmouth both reverted to testing requirements citing research that showed the exact opposite for their applicant pools.

So which is it? Does requiring test scores help or hurt accessibility for underserved students? The answer appears to depend on who is doing the research.

Lee Coffin and Jeremiah Quinlan, admissions deans for Dartmouth and Yale respectively, both said that under test-optional policies their colleges were more likely to take a chance on a student from an unfamiliar school—often lower-income, non-white applicants—if they included test scores in their application.

Deming said the data supports that conclusion, and that grade inflation during the pandemic will only exacerbate the issue under test-optional policies.

“Most high schools, you look at a straight A student, you have no way of knowing whether they can do the kind of work at a place like Dartmouth or Harvard because you've never taken a student from that school before. You don't know how hard it was to get the A,” he said. “So you end up falling back on another type of school where you’ve taken 10 students a year for the past couple of decades.”

Bastedo said that at Michigan, one of the most selective public colleges in the country, that hasn’t been the case.

“Our data didn’t suggest a need to reinstate requirements to ensure academic preparedness, as Dartmouth’s did,” he said. “And we came to very different conclusions about diversity, too.”

Bello said arguments for test requirements along these lines betray a more ideological motivation behind the veil of data-driven rationality in which Yale and Dartmouth have swaddled their new policies.

“I don’t question that popular colleges are looking for any way to distinguish between applicants. What I do question is their preference for the metrics they like,” he said. “What’s been made increasingly clear is that these choices to revert to testing requirements are not really about the data. What it’s about is faith. These institutions get a sense of comfort and confidence from these tests as predictors of a certain kind of success that they value.”

Bastedo doesn’t believe colleges like Yale and Dartmouth are fudging the data for their own purposes—their research is sound, he said, if narrowly tailored. But he also doesn’t quite buy their public rationale.

“I’m not sure diversity is the reason these places are going back to requirements. They’re very worried about being accused of not caring about equity, so they’re leading with that,” he said. “I wish a more balanced case was being made, but I'm a researcher, and they're advocates for a particular outcome. They're using data that supports that outcome.”

Nothing resembling a testing consensus, or even a solidified lack of consensus, has emerged yet. Most colleges are biding their time making a decision: Harvard extended its test-optional policy until 2026; Cornell extended its optional policy another year, and Vanderbilt pushed its decision until 2027.

Many large public institutions are also playing the waiting game. Of the 14 institutions in the Big 10 athletic conference—popular destinations for students from across the country—only five have made long-term decisions on testing, all for very different reasons: Indiana University-Bloomington, which is continuing the test-optional policy it adopted in 2020, a few months before the pandemic; Purdue University, which reinstated requirements in 2022; the University of Iowa, which went test-optional after a Board of Regents vote that same year; the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, which was forced to drop testing requirements after the state government passed a law mandating the move for all public colleges; and now, Michigan.

Bastedo said he expects most institutions want more time to collect data and make an informed decision. He thinks that’s probably a smart move.

“All the student success data from the past few years came in during that pandemic, so it feels contaminated. Anytime you analyze that data, you're always putting out these caveats that make you uncomfortable coming to any sort of definitive conclusion,” he said. “We don’t have all the information we need, and yet we’re at a point where it feels like we need to be making decisions.”