You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Princeton University Press

A lot has changed since Nicholas Lemann last wrote about college admissions tests in his 1999 book, The Big Test. A progressive movement against standardized test requirements took off in the 2000s, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the majority of colleges to make test scores optional and the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in admissions, making the question of testing’s impact on college diversity more relevant than ever.

The longtime New Yorker writer’s new book, Higher Admissions: The Rise, Decline, and Return of Standardized Testing (Princeton University Press) grapples with the effects of those changes and roots them in the complicated history of the first standardized college admissions exam, the SAT. He charts a path from its origins as an IQ-based aptitude test designed to help highly selective colleges expand their talent pool to its ubiquitous acceptance in the 1980s and ’90s and to the contentious debates over its fairness that erupted, faded and returned again.

Lemann spoke with Inside Higher Ed about the past, present and future of college admissions exams and how their evolution is inextricably tied up with efforts to integrate and democratize American higher education. The conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Q: The last time you wrote about standardized testing was in 1999. In revisiting the topic 25 years later, what surprised you most about the way testing, and higher ed’s attitude toward it, has evolved?

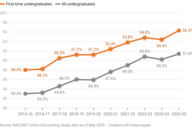

A: The thing that’s most surprising happened just as the book was going to press. I was pretty clear how the big affirmative action case of last year in the Supreme Court was going to go, and because of COVID—but I also think in anticipation of the decision—many or most universities had already suspended SAT and ACT requirements. I had thought that colleges were sort of keeping their powder dry, and if they lost that case they would then just keep testing optional forever. And I was very surprised by the number of universities that have reinstituted requirements since then. It’s not a huge wave, but it has been significant.

Q: You write that “the era of aptitude-based testing as an admissions device may be coming to an end.” Are you saying the past year has challenged that prediction?

A: I don’t have a definite answer. One thing is, the United States is very obsessed with elite college admissions and minute variations in the composition of the classes at 25 or 50 of the top universities. You can be super rational and say that so few schools don’t make that big of a difference. And it would make way more difference to deal with, you know, the problem of noncompletion of higher ed degrees. But it’s difficult to get the kind of attention for the broad end of the higher ed landscape in many circles. I live in one of the most liberal enclaves in the country [the Upper West Side of New York City], and if I’m walking my dog and I’m talking to a neighbor about the number of Americans without degrees, that is unfathomable to them. It’s just off their screen.

Q: In the book you write that “a great deal of trouble has come from our tendency to conflate elite selection with mass opportunity.” Do you think the purpose behind the SAT has changed substantially since its inception as what you call an elite selection tool?

A: I think the de facto purpose has not really changed since they started. Henry Chauncey [the first head of longtime SAT administrator Educational Testing Services] was somebody I got to know very well, and I don’t think he particularly had a vision. He was an incredibly good administrator of a nonprofit organization, but he just sort of believed tests are good because they’re scientific and science is good. I think [James] Conant [former Harvard president and architect of the SAT], who was sort of his mentor, did have a vision that was very clear, and it started as wanting to change the kind of person that goes to Harvard. And then it became, “I want to change the kind of person who goes to Ivy League schools,” or the then-small membership of the College Board. And then it gets into World War II and the Cold War, and his rhetoric becomes grander, and the SAT becomes more of a mass device. It’s basically The Republic by Plato: He thought you should have a society that is run by an intellectual elite plucked out of their origin, who will then be whisked away to be educated for free at the great universities and then go on to become these technocratic public servants. The SAT was designed as a tool to do that.

There’s this idea that if we produce a small number of people who come from nothing and get to the top, then that proves we have a good society.”

Q: Earlier this year, Dartmouth, Yale and other universities, in deciding to bring back test requirements, argued that standardized tests can actually enhance diversity and equity because they allowed admissions officers to find exceptional applicants from underresourced schools and regions that they otherwise might not look at. What do you make of that argument?

A: There’s this prevailing diamond in the rough theory, or what I call Cinderella at the ball theory. But the number of people in the U.S. who come from the bottom half of the income distribution and get 1500-plus combined SAT scores is a really, really small number. I could not get the College Board to give me the number straight up, and I tried, but I know it’s very small. So the question is, how much do you want to engineer a whole system just to find these few people?

[Raj] Chetty [head of the research firm Opportunity Insights, whose research was cited in many college decisions to reinstate testing] and his team are really into this old-fashioned meritocratic ideology. It’s incredibly appealing to people, and it’s nothing new. If you go back and read all the Horatio Alger novels and all the popular rhetoric from the 19th century about log cabin presidents, there’s always been this literature in America about how Andrew Carnegie started from nothing and so on. It hits the national soul in a big way. There’s still this idea that if we can produce a small number of people, an almost anecdotal number of people, who come from absolutely nothing and get to the top, then that proves we have a good society.

Q: Some of what might be thought of as mass social mobility efforts in higher ed were being made around the same time that the SAT was established. You write about the GI Bill and the postwar expansion of college access; how did that intertwine with the SAT’s history?

A: It’s very interesting, because most people I talk to about this who haven’t really thought about it that much, they think the GI Bill and the SAT are exactly in the same spirit. But of course, they weren’t. And the father of the SAT, [James] Conant, was against the GI Bill. He’s a really interesting character, because he saw himself as a democratizer, but he was also very elitist. And Clark Kerr [former president of the University of California system, under whom the system became one of the first to require the SAT for admission in 1967], who I also was fortunate enough to get to know pretty well, he was sort of the same way. He was keenly aware of being in a public university system, but it was very rank ordered.

Q: What effect has the normalization of these standardized admissions tests had on American high school education?

A: These tests have become very important for the people who don’t get into elite schools, too—not just the people who do get into elite schools. If we had a curriculum-based testing system where everybody in high school was taking very similar curriculum and they were tested on the mastery of that curriculum, as is true in many developed countries, then the person who isn’t going to go to an elite school benefits because they’ll study harder and try to get a better score. Instead, the curriculum is infused with preparation for these tests that, for most students, just don’t matter much.

The issue is not necessarily testing itself, per se. Tests are tools that serve purposes and visions. If I go to your house and I think your house really sucks in some way—it’s ugly, it’s unstable or something—and I said to you, “The real problem with your house is the hammer that the carpenters were using to build it,” that would be obviously absurd. It would be the design and so on. But with testing, somehow people don’t see the design behind it. And so instead of arguing about the vision and the purpose, they argue about the test itself. If you think there’s a problem with the way American higher education is set up, rather than trying to fix the tests, you’re better off fixing the vision behind them.

If you think there’s a problem with the way American higher education is set up, rather than trying to fix the tests you’re better off fixing the vision behind them.”

Q: Colleges have largely responded to growing public criticism of standardized tests by making them optional or not considering them at all; there have been no recent efforts to revise the SAT or ACT along lines that might make them more equitable. Why do you think that is?

A: A few reasons. One is that, from a technical standpoint, it’s all about the predictive validity coefficient [the equation used to trace tests’ ability to predict academic performance in college]. The problem has always been that, within the testing world, all of these proposed reforms that could make the tests as instruments a lot more fair then start degrading the project of predictive validity. It stands to reason that, if you’re my kid, growing up on the campus of Columbia University [where Lemann teaches], it’s not going to be a big culture shock to go to college, compared to a low-income Black or Latino student. So if you’re trying to design an instrument to have the highest possible predictive power for first-year grades in college, that difference constrains you.

The second [reason] is our lack of a national curriculum. We saw the fascinating and spectacular failure of the Common Core as an example of the difficulty of having a national curriculum in the U.S., which is really an outlier; other countries don’t have this issue because they have national curricula and they have a curriculum-based test. There was a test proposed to go along with the Common Core, called Smart Balance, that would have been our version of this.

The other reason is faculty. I don’t know if you’re old enough to have heard an older relative who would say, “Let me tell you about my first day in college,” law school, whatever, where the professor gets up and says, “Look to the left of you. Look to the right of you. One of those people won’t be here next year.” That was kind of how it used to work: They had an audition flunk-out method, which was a big pain in the neck for professors and administrators. The SAT was a way of ensuring that the students are going to be like mini versions of the faculty—they’re not going to need a lot of remediation and counseling, and they’re going to be almost certain to graduate from the minute they get their acceptance letter. To faculty, that is very attractive.

Q: The book focuses on affirmative action as well, tracing how debates about the two issues have intersected through the years. Writing about the effect of the affirmative action ban, you say that “colleges won’t be able to continue their preferred course of embracing both tests and racial integration post–[Students for Fair Admissions]. They’ll have to choose one or the other.” Is the choice so stark?

A: I may have put it a little dramatically, but it’s true. People who don’t like affirmative action usually think standardized tests are the opposite of affirmative action. What’s weird is that within almost the same time frame, places like Harvard adopted both SAT requirements and affirmative action. These are complicated institutions; they try to be a lot of different things at the same time. And as long as there was affirmative action, there didn’t have to be this big trade-off in diversity efforts. The two could sort of uneasily coexist. But you also started seeing lawsuits being filed very early on in the adoption of affirmative action, and the lawyers always used test scores as evidence that the plaintiff was being discriminated against.

Admissions at these institutions is a box that we’re not often allowed to see the inside of. And when you do you get a sense of just how oppositional the effects of affirmative action and standardized test requirements are … it is very stark.