You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A new report found little change in the socioeconomic makeup of elite colleges over the last century.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | antpkr and prill/iStock/Getty Images

The proportion of low- and middle-income students at highly selective colleges was the same in 2013 as it was 1923, despite a massive expansion in broad college access.

During that century, the college-going rate for Americans skyrocketed from 10 percent to more than 60 percent. But no historical development, from the GI Bill to the introduction of standardized testing, meaningfully changed the socioeconomic makeup of elite institutions.

That’s the groundbreaking finding of a new study from the National Bureau of Economic Research, conducted over the course of five years using a century of income and enrollment data from 65 of the most selective public and private universities in the country.

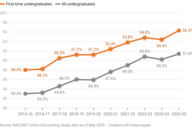

In the early 1900s, around 8 percent of the overall college population came from the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution; by the 2010s that had greatly improved, with 13 percent of male college students and 20 percent of female students coming from the bottom 20 percent. But according to the study, no such change occurred at highly selective colleges.

“Students with parents from the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution have consistently made up approximately 5 percent of the student bodies at these institutions throughout the last century,” the study reads.

It’s nothing new that wealthy colleges with low admission rates enroll a vastly disproportionate number of wealthy students; a 2017 report found that many of the colleges featured in the NBER study enrolled more students from the top 1 percent of wealth earners than from the bottom 60 percent.

Ran Abramitzky, an economics professor at Stanford University and one of the study’s authors, said the research upends the traditional story of elite higher education’s slow but steady “democratization.” He noted that highly selective institutions have made substantial efforts to encourage low- and middle-income enrollment—especially in the past decade, a period the study does not cover.

But the conclusion of his research is hard to misinterpret: America’s top colleges are no less elitist now than they were during the Roaring Twenties.

While socioeconomic diversity stayed constant, racial and geographic diversity increased significantly over the same 100 years, the study found, with an unsurprising spike in Black representation after the civil rights movement.

The study includes data from 30 selective public flagships, all eight Ivy League universities, eight historically women’s colleges and 15 liberal arts colleges, along with Stanford, Duke, MIT and the University of Chicago.

To compile what the study describes as “the most comprehensive dataset of students’ socioeconomic backgrounds,” Abramitzky and a team of researchers visited university archives and combed through a century’s worth of yearbooks, digitizing their contents and matching the information of 2.5 million students with U.S. Census data to ascertain their family income.

Some exceptions to the trend emerged. Elite women’s colleges enrolled a much higher percentage of low-income students in the early 21st century than the early 20th, for instance, as did the 30 selective public institutions. At the University of California campuses in Los Angeles and Berkeley, for instance, the proportion of students from the bottom 20 percent of income earners rose seven percentage points over 100 years.

But for the most part, the stagnant class makeup was “remarkably similar across all elite private institutions,” according to the study.

Abramitzky said that while he expected a lower rate of economic diversification at the Ivy-plus colleges than at most, he was shocked to find almost none at all.

“That kind of persistence, over 100 years, that did surprise me,” he said.

The Myth of ‘Democratization’

The study also tracked the effects on colleges’ socioeconomic diversity of two major milestones in college admissions: the passage of the GI Bill and the widespread adoption of standardized testing. It found that neither had a significant impact on low-income enrollment at highly selective institutions.

“These were two of the major policy changes in the history of American higher education—the GI Bill was supposed to alleviate financial constraints and the SAT was supposed to give everyone a shot to get into these elite colleges,” Abramitzky said. “But these two interventions had little success in increasing the representation of low- and middle-income students.”

The study found a sizable bump in middle-class representation and a decline in upper-class students after the GI Bill was passed in 1944. But there was no corresponding increase in low-income enrollment; in fact, the study contends the bill may have led to a decline in low-income representation at public colleges.

The middle-class surge did not last, either. Before World War II, students from the top 20 percent of wealth earners made up 70 percent of students at highly competitive private colleges and 55 percent at selective public colleges, according to the report. By the early 1980s, those numbers had fallen to 50 percent and 40 percent, respectively—but by the end of the decade they had reverted to about the same proportions as in the prewar period and have not moved significantly since.

“We see little evidence that lower- and even middle-income students attended elite colleges at higher rates due to the [GI Bill],” the report concludes. “These findings suggest that removing financial barriers to access was not enough to countervail pre-existing inequalities.”

The study also shows that standardized test scores had a negligible impact on low- and middle-income enrollment at highly selective private institutions and caused “a relatively small and short-lived increase in the proportion of lower-income students at elite public colleges.”

That finding contradicts the claims made by many institutions that support requiring test scores: that they allow them to discover and admit more exceptional candidates from poor neighborhoods and underfunded high schools who might not otherwise stand out.

Abramitzky stressed that he did not have access to admissions data, and the study makes no claims regarding class bias in selective colleges’ application processes. But he speculated that efforts like the GI Bill and the SAT were unable to make a significant difference in students’ admissions prospects because they were not targeted to benefit low-income students specifically, or came too late in a student’s education.

Abramitzky said the report is just the first in a planned series using the data set of student income, and that he wants to expand his research to more open-access institutions as well. But admission to a top college is more directly tied to income and success than ever, he said, and studies suggest that one’s family wealth is a determining factor in that admission to begin with. For that reason, Abramitzky hopes his research helps inspire a change not seen in 100 years.

“It used to be that whether you went to college is what made a difference in a person’s life and prospects,” he said. “Today it’s increasingly about whether you went to an elite college … so maybe the consequences for this are more important now than ever.”