You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Ball State University runs a number of summer bridge programs to smooth the transition for incoming first-year students. One of them, Jump Start, is a five-year-old initiative designed to help first-generation and minority students acclimate to the unfamiliar academic and social environment of a college campus.

This year Jump Start will have no particular focus. It will be, to use a phrase university leaders have grown fond of repeating since the Education Department issued a Dear Colleague letter banning diversity, equity and inclusion efforts in February, “available to every student.”

Over the past two months, administrators at the public university in Indiana made changes to the program to de-emphasize its focus on underrepresented students, according to one Ball State employee who requested anonymity to speak freely about their experience.

While Jump Start has always technically been open to any interested student, the employee said, first-generation students and students of color were typically granted priority for its limited spots; staff were given lists of those students so they could inform them about the program.

“We were told to reach out and let them know about this great opportunity,” the employee said. “They kind of got preference for the program.”

But at planning meetings for summer bridge programs in April, the employee said, “The tone was very different.” Administrators told staff to broaden Jump Start’s focus and stop targeted outreach to first-gen and minority students. They were not given any lists and were told there would be no question about identity on the student application forms.

“There was a strong emphasis on communicating that this program is for everyone at the expense of those who need it most,” they said. “I was really taken aback … we were not even allowed to have control over our own program applications.”

The employee said the university is eliminating Jump Start after next academic year, along with all its other summer bridge programs—including one for students with disabilities and one run by the Multicultural Center. Instead of applying to a cohort-specific program, all Ball State first-year students will be required to attend a pre-orientation before the semester begins.

“That change defeats the entire purpose of summer bridge programs,” the Ball State employee said. “These students are going to get lost in the whole class.”

The employee believes such changes are grounded in politics. In April, shortly before the summer bridge planning meetings began, Ball State’s Board of Trustees approved a resolution to end all diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and disband the university’s Office of Inclusive Excellence. In a video addressing the university community released in April, Ball State president Geoffrey Mearns said he was guiding the university through an “intensive exercise” to ensure they “complied fully with President Trump’s executive order” banning DEI.

“We modified some programs to ensure that these programs are available to every student,” Mearns said in the video.

A spokesperson for Ball State declined to answer multiple questions or address the employee’s claims, including about whether the Jump Start program is ending after this coming year and the university’s rationale for altering the program’s application process.

The Trump administration’s broadside attacks on DEI—as well as legislation passed in a number of states, including Indiana—have already upended a wide range of programs and services for minority and underserved college students, from LGBTQ+ centers to scholarship offerings for Black students.

Now some colleges running pre-matriculation programs for underrepresented students are turning away from those efforts, eager to avoid a conflict with the administration and the risk of losing federal funds over initiatives that might be flagged as DEI. Advocates raised concerns about this possibility in 2023, after the Supreme Court banned affirmative action in admissions, but the ruling hasn’t had much effect on bridge programs until now.

Much of this is happening quietly, in the form of program name changes, website scrubbing and revisions to eligibility requirements. Some programs once administered specifically to benefit underserved students have received orders from university administrators to broaden their reach. Others are slated for complete elimination.

Zenia Henderson, chief program officer for the National College Attainment Network, said that in the current regulatory and political environment, “pre-emptive compliance” is the norm.

“I do think a lot of institutions are folding in order to avoid the headache of a fight,” she said.

Fears of Regression

Summer bridge programs weren’t always focused on underrepresented students per se. Aaron Brown, executive vice president at the Council on Opportunity in Education, said that when he helped establish a bridge program at Eastern Washington University in 2011, common practice was to offer remedial academic courses for students who were accepted conditionally. They tended to be lower-income students from neighborhoods without college prep classes, but whom those students were was less important than where they fell on the academic-preparedness scale.

In the last decade, the role of summer bridge programs shifted substantially, Brown said, to focus on helping students transition to a campus environment that might look substantially different from their high schools and neighborhoods, and to find belonging and support in a new community. Often those efforts were focused on first-generation, Black and Hispanic students.

“These on-ramps have been built over the years in ways that are very strategic and thoughtful and aimed at helping these students when it matters most, in the first few weeks of college,” Brown said. “It stands to reason that if you get rid of that focus, we could return to the lower achievement outcomes we saw a few decades ago.”

According to documents obtained by Inside Higher Ed, the early framework for Ball State’s Jump Start program was centered around diversity, equity and inclusion efforts. The university’s initial grant proposal to the Eli Lilly Foundation cited a 2018 Indiana Commission for Higher Education report, which found that 50 percent of white students met the state’s early college success indicators by their sophomore year, compared to 38 percent of Hispanic students and 23 percent of Black students.

In the proposal, Ball State officials said addressing those gaps was a “high priority” for the program, noting that the grant money would be used to “better support underserved students … who are most in need of early preparation.”

The Ball State employee said that as a first-generation student themselves, they “would have really benefited from a program like” Jump Start when they went to college. Seeing those programs lose their responsiveness to gaps in college achievement, they said, is heartbreaking.

“This is literally counterproductive to student success and retention, which is what Ball State and higher ed in general have said they’re focused on for years now,” they said. “You can’t address student success when you’re leaving out the most vulnerable populations.”

Quiet Compliance

Last month, the University of California, Berkeley, announced that its summer bridge program, which has run continuously since 1973, would go “on pause” this summer. Less than two weeks earlier, the Department of Justice launched a civil rights investigation into admissions practices at Berkeley and two other California colleges, alleging they were circumventing the Students for Fair Admissions decision.

Summer bridge program leaders at Berkeley said it was suspended because of staff capacity issues. A hiring freeze in the Student Learning Center and a failed search for a new Summer Bridge coordinator “limited our ability to deliver the program at the high standard we’ve upheld over the years,” they wrote in an email.

While they work to get the program back up and running, they “remain deeply committed to serving the broad and globally diverse population historically reached by Summer Bridge.”

Brown said that such on-campus transition programming is “incredibly expensive,” and many colleges are finding the risk of liability to be too much to add on top of the high cost of operations.

“Colleges are taking a pause to re-examine the scope and focus of these programs for lots of reasons,” he said.

A raft of state anti-DEI laws has also pushed colleges to reframe or overhaul their initiatives in the past year; newfound backing from the federal government, including the threat of federal funding cuts, has only ramped up the pressure on institutions.

For 15 years Utah Valley University’s Latino Scientists of Tomorrow program helped introduce Hispanic high school students to the institution and to STEM career pathways. Last year, UVU renamed the program Empowered Professionals of Tomorrow. A UVU spokesperson said the change was made to “align with the passage of Utah HB 261,” a sweeping anti-DEI bill passed in January 2024.

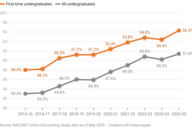

Kimberly Jones, president of the Council on Opportunity in Education, said a major backslide in intentional college transition programming could have downstream effects not only on racial college achievement gaps, but on college-going rates for underrepresented students—just when they were beginning to improve.

“You’re dealing with certain pockets of students who were already timid about pursuing postsecondary education,” she said. “Now there’s another symbolic roadblock put in front of them in the absence of summer bridge programs … I think we could definitely see a regression in college-going.”

Henderson, from NCAN, works with hundreds of nonprofits and community-based organizations that help run precollege programs for underrepresented students, or at least connect students with those opportunities. She said those organizations are concerned their work will soon be seen as toxic for risk-averse universities.

She added that even if programs only change their names and practices, vulnerable students are likely to pay the price down the road.

“Colleges aren’t necessarily doing away with these programs yet, but we are seeing a shift in language, in eligibility, in outreach,” she said. “Once you change the core purpose of something, it will eventually transform into something else.”