You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

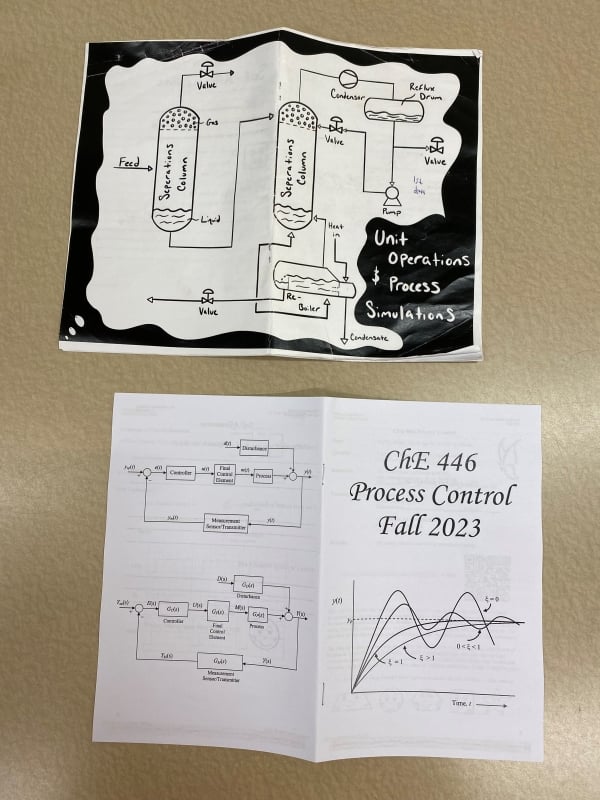

The latest edition of Anna Marie LaChance’s syllabus zine was distributed to students this fall.

Anna Marie LaChance

Getting students to read syllabi is a problem for instructors as old as the syllabus itself.

Many professors have created activities to incentivize syllabus reading or planted “Easter eggs” within their documents that offer a reward for diligent students who don’t skip blocks of text.

Anna Marie LaChance, a lecturer of chemical engineering at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, designed her syllabus as a zine, making the information more approachable and user-friendly and connecting learners to critical academic and nonacademic resources.

What’s a zine? A zine, as defined by Merriam-Webster, is “a magazine but especially a noncommercial often homemade or online publication, usually devoted to a specialized and often unconventional subject matter.”

The University of Texas Libraries ties zines back to 1930s science fiction fanzines, but they’re most known for underground social and political activism roots in the 1960s. Most zines are produced by hand in editions of fewer than 1,000 and represent a minority interest.

Zines also have a place in LGBTQ+ history; the 1980s and 1990s they spread information, provided resources and elevated stories of LGBTQ+ individuals.

“The zine fundamentally is a nontraditional form of knowledge sharing,” LaChance, who is a trans woman, says. “It’s this very queer, feminist form of knowledge sharing, and I love that.”

The inspiration: The idea of a magazine-style syllabus first came from the Abolition Science podcast, which featured two episodes on tech zines and a syllabus zine.

“That whole idea of a syllabus that was also a zine just immediately captured my imagination,” LaChance says. “It’s not a big, expensive engineering textbook with 500 pages. It’s something that I, your instructor, made with love.”

The vision of the zine was to be something students could continually reference and engage with throughout the term, addressing academic and nonacademic concerns.

The how to: To create her zine, LaChance started by reformatting all the material present in her syllabus into a handheld booklet. She then edited out the material not absolutely necessary in a print format, like course progression or assignment deadlines (all still present on the learning management system).

“I cut out a lot of the extraneous details … just, like, long-winded explanations of what the homework is and like how to submit projects and things like that, and I replaced it with actually useful advice,” LaChance says. One tip: students should save their work to their personal drive before logging out of the MATLAB software or virtual desktop to secure their work.

LaChance also commissioned her then undergraduate mentee at the University of Connecticut, Nia Samuels, to create art pieces to complement the zine.

Nia Samuels, a chemical engineering graduate from the University of Connecticut designed LaChance's first syllabus cover (above) and LaChance designed the latest edition cover (below).

Anna Marie LaChance

The zine first rolled out in fall 2021 and over the years, LaChance has made edits to shrink the document from 32 to 16 pages and to reflect student needs. Initially, the syllabus had a grade calculator table so students could track their progress in the course, which LaChance has since removed as she’s engaged in ungrading.

New additions this fall include QR codes to give students immediate access to online resources and doodling space.

The impact: The zine accomplishes four goals.

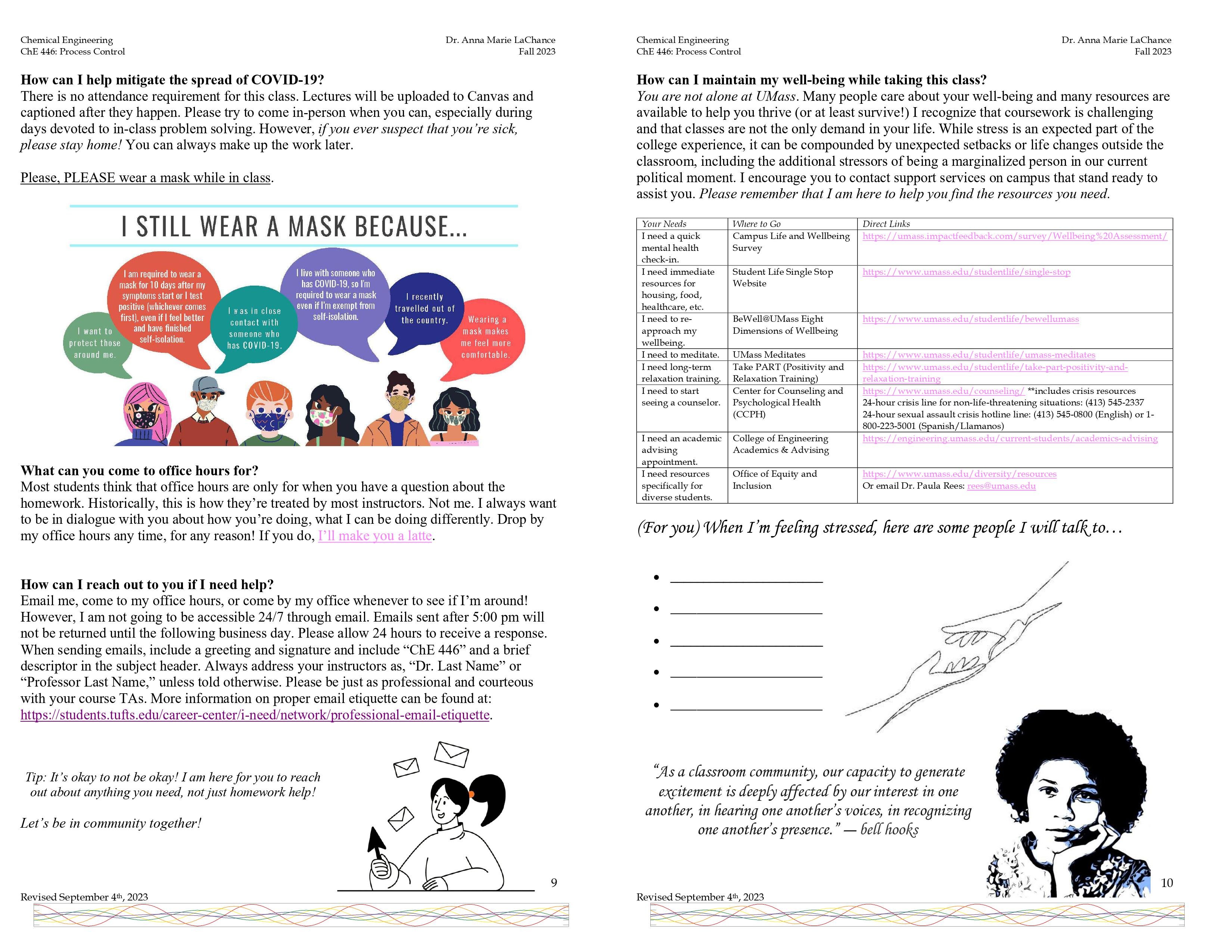

- It makes information presented more engaging and personable, with the official legal copy present from the institution, but also an informal, personal message from LaChance about what academic policies mean in her classes.

- It allows for creativity in design and format. Samuels created “squishies,” or little drawings of shapes that offer helpful tips for academic success that are sprinkled throughout the document. Different editions of the zine have had reflection pages or fill-in-the-blanks, as well.

- It creates space for additional resources. The zine features a list of formulas students may need for homework or tests and nonacademic supports like mental health services at the university.

- It sets an approachable tone for LaChance. “Relationship building is so core to my political philosophy and my teaching philosophy,” LaChance says, so she incorporated her beliefs in creative ways throughout the zine to make it clear to students that she cares for them.

The zine is just one portion of LaChance’s pedagogy, but as a syllabus, it helps set the tone she wants on the first day of class, which she says has made a difference in sharing her values of diversity, equity, justice and inclusion and her emphasis on mental health.

LaChance includes information about her masking policy, office hours and student support services within her magazine.

Anna Marie LaChance

DIY: For professors looking to make their own zines, LaChance offers some advice.

- Research the logistics. Creating a zine from scratch can be a learning curve. LaChance puts her zines together by hand, which requires finesse in organizing pages and using an extra-long stapler.

- Look for model syllabi. Other faculty members have created graphic syllabi, including digital syllabi, which can serve as inspiration.

- Understand your students’ needs. Each discipline will have its own needs for course content, and each institution has its own services that students can be connected to.

- Be creative. The STEM field, in general, can scorn creativity that is not “professional,” LaChance says. “But why can’t this be professional? … Like, can you have little butterflies and pride flags? Who cares?”

Do you have an academic success tip that might help others encourage student success? Tell us about it.