Free Download

Professors are slowly gaining confidence in the effectiveness of online learning as more of them teach online, Inside Higher Ed's 2017 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology reveals.

While faculty members remain slightly more likely to disagree than to agree that online courses can achieve student outcomes that are as good as those of in-person courses, the proportion agreeing rose sharply this year, and the proportion strongly disagreeing dropped precipitously.

This year’s survey, conducted as in previous years in conjunction with Gallup, examines the views of 2,360 faculty members and 102 administrators who oversee digital learning at a range of institutions -- public, private nonprofit and for-profit, two-year and four-year -- across the United States. The Online Learning Consortium provided the sample of digital learning leaders and contributed to development of the survey questionnaire. The survey report can be downloaded here.

Among the findings:

- Faculty members overwhelmingly doubt whether online learning can match in-person courses in reaching at-risk students and in rigorously engaging students in course material.

- Seven in 10 faculty members who have taught an online course say the experience helped them develop pedagogical skills and practices that improved their teaching, online and in the classroom.

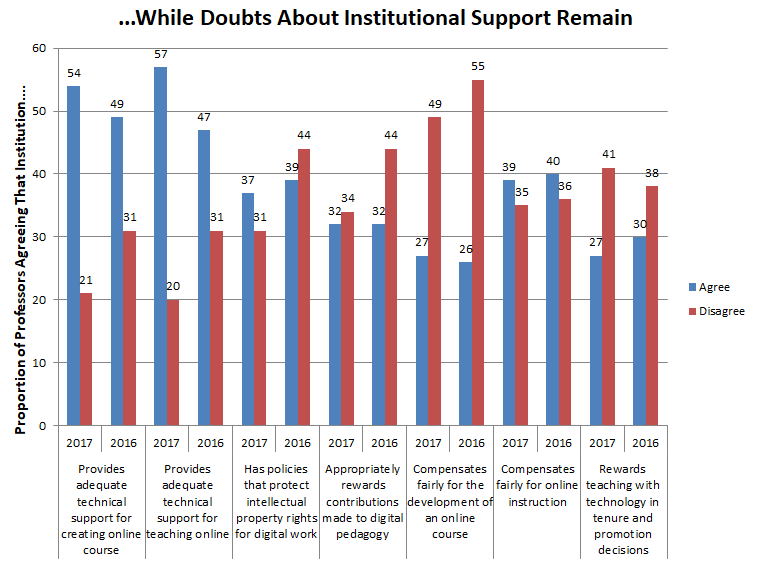

- Professors and digital learning leaders disagree about the level and quality of their institutions' support for teaching online, with a third or fewer of instructors agreeing that their college appropriately rewards teaching with technology or contributions to digital pedagogy, or acknowledges the time demands or compensates fairly for developing an online course. A majority of instructors, though, say their institutions provide adequate technical support for developing and teaching online courses.

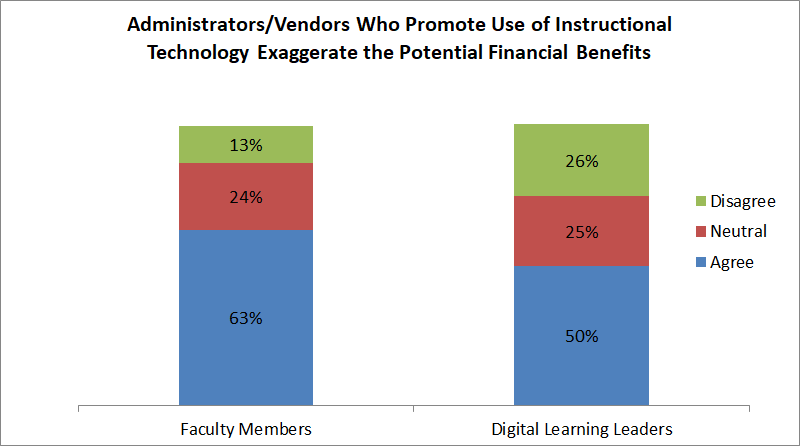

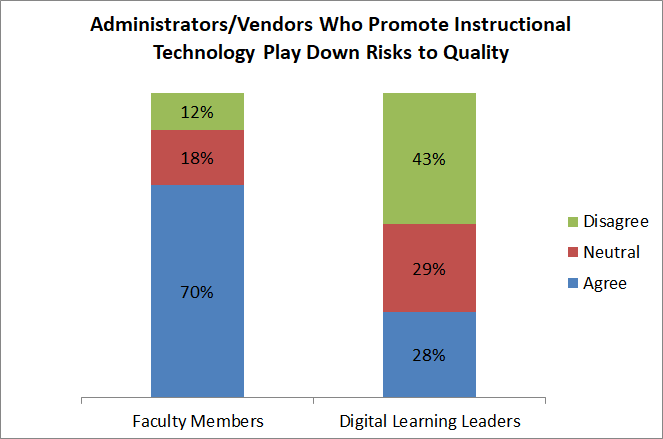

- Two-thirds of professors agreed that administrators and vendors "exaggerate the potential financial benefits" of instructional technology and "play down the risks to quality" posed by it.

- More than nine in 10 faculty members and digital learning leaders say textbooks are priced too high. The vast majority of both groups also say instructors should significantly consider price when assigning course readings and should assign more open educational resources.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2017 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Thursday, Nov. 16, at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Register for the webcast here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology was made possible in part with support from D2L, Jenzabar, Mediasite by Sonic Foundry, Pearson and VitalSource.

A Turning Tide

It has become a common trope in some circles that many professors are Luddites, impeding innovation in higher education and generally opposing efforts to use technology to change how students learn. The survey's results challenge that simplistic meme.

A full third of instructors, 35 percent, characterize themselves as "early adopters" of new education technologies, and 55 percent say they "typically [adopt] new technologies after seeing peers use them effectively." Just 10 percent describe themselves as "disinclined to use educational technologies."

A solid majority, 62 percent, strongly agree (29 percent) or agree (33 percent) with the statement "I fully support the increased use of educational technologies." Just 8 percent disagree or strongly disagree.

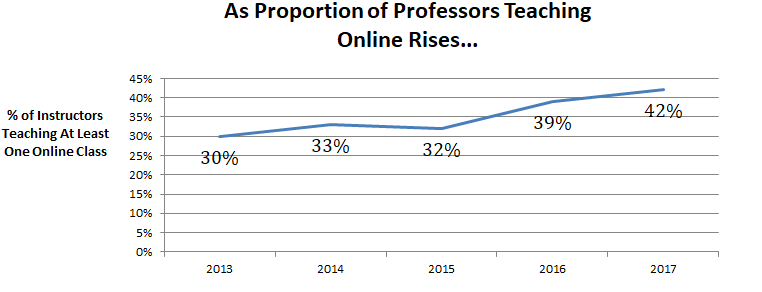

That support is evident in the gradual increase Inside Higher Ed's surveys have shown in professors' actual practice. In 2013, 30 percent of instructors said they had taught an online course. In this year's survey, 42 percent reported that they had taught a fully online course for credit, up from 39 percent in 2016, as seen in the graphic below. Thirty-six percent said they had taught a blended or hybrid course mixing in-person and online elements.

The proportions were roughly comparable by instructor status -- tenured, nontenured, etc. -- but differed widely by institution type, with public college professors (46 percent) far likelier than their private college peers (21 percent) to have taught online.

"It appears to be moving from the early adopters to the mainstream," said Rebecca Griffiths, a senior researcher in SRI International's Center for Technology in Learning. "It's not just the adjuncts who may not have a choice anymore."

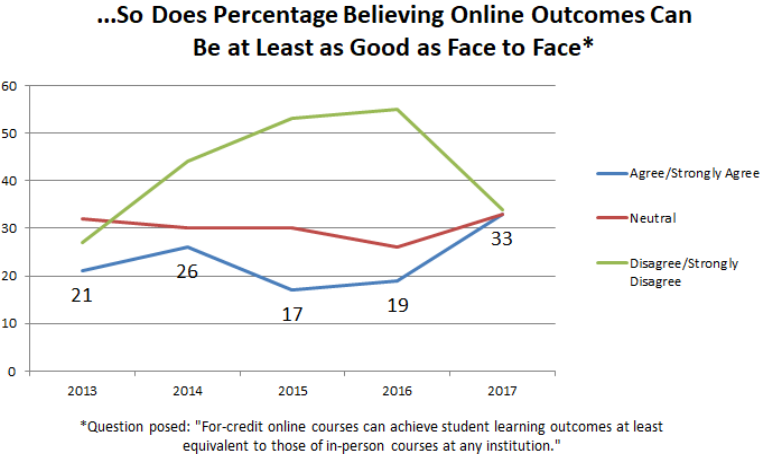

That increasing experience may be among the factors driving growing confidence in online learning. In the Inside Higher Ed/Gallup surveys from 2013 to 2016, roughly one in four agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “For-credit online courses can achieve student learning outcomes at least equivalent to those of in-person courses at any institution.” (The numbers were similar, if slightly higher, when instructors were asked about online courses at their own institution, and in the classes they themselves taught.)

This year, though, 33 percent of faculty members agreed with that statement, up from 19 percent in 2016, a 14-percentage-point swing. That matches the proportion that disagreed, as seen in the graphic below.

Professors who have taught online were significantly likelier to express confidence in the efficacy of digital courses. Forty-five percent of those who have taught online agreed or strongly agreed that the online courses at any institution could achieve student learning outcomes at least as good as in-person courses; the figure for those who had not taught online was 24 percent.

Professors who have taught online were significantly likelier to express confidence in the efficacy of digital courses. Forty-five percent of those who have taught online agreed or strongly agreed that the online courses at any institution could achieve student learning outcomes at least as good as in-person courses; the figure for those who had not taught online was 24 percent.

The split was even larger for courses at the professors’ own institution (61 percent of those who had taught online versus 28 percent of the rest), and larger still for the instructors’ own courses (65 percent versus 15 percent).

The 14-percentage-point change in professors' view of the efficacy of online courses between 2016 and 2017 is striking, and explanations for it are unclear.

Inside Higher Ed and Gallup changed the order of the survey questionnaire from last year to this year, and it is possible that change might have influenced the responses.

Gallup also notes that the weighting of the faculty sample changed slightly in this year’s survey, in a way that slightly elevates the views of professors from public colleges and universities. But Gallup data scientists said they do not believe that had an effect, since similarly sized increases are evident for professors from all sectors, public and private, two-year and four-year.

Experts in online learning said they believed that while those factors might have exaggerated the size of the change in faculty attitudes about online courses, the overall trend was unmistakable: either because more instructors have experience with online learning or for other reasons, belief in its efficacy is slowly growing.

Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, which itself has conducted numerous surveys about faculty views on online learning, said the change in faculty attitudes was somewhat surprising, but absolutely possible. “We have a larger percentage of people who have experience online, and we know that once you have experience with something you tend to be more positive about it. That alone could have some level of impact, but probably not this level of impact.”

Other possible factors, Seaman said, could be “acceptance of the inevitable” among faculty members, “even if they don’t like it.”

Some Deep-Rooted Concerns

While faculty attitudes about online learning appear to be improving, the degree of acceptance and embrace should not be overstated. Many faculty members continue to have doubts about the effectiveness of technology-enabled learning, and the motivations for it.

Asked to compare the efficacy of online versus in-person courses on a range of objectives, overwhelming majorities of professors said they believed online courses were less effective in letting instructors interact with students during class time (86 percent) and reaching at-risk students (79 percent).

Three in five said it was more difficult online than in person to rigorously engage students in the course material and to maintain academic integrity, and half said online learning was less effective than in-person courses in delivering the necessary content to meet learning objectives. (The only ways in which online modalities were seen as at least as effective as face-to-face courses were on relatively practical matters such as grading, communicating about grading and communicating with the institution about logistical issues.)

More Coverage of Online Learning

Each week Inside Higher Ed's

"Inside Digital Learning" newsletter

brings you the latest news you can

use about the use of technology

in instruction. Sign up here.

And while those who have taught online held somewhat more positive views, majorities still said that online education is inferior to in-person instruction in interacting with students and reaching at-risk students.

Adrianna Kezar, a professor of higher education and co-director of the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the University of Southern California, said those numbers reflect the widespread faculty view that digital learning should be deployed "judiciously."

"Online learning works best when used with students that can benefit from this mode of education," she said via email, specifically citing the responses about at-risk students. "Not everyone thrives in an online environment. We need to be more judicious in our use of online learning -- making it an option for those who can thrive in that environment and not forcing at-risk and first-generation students into this mode of learning."

Unmet Promises

Significant faculty skepticism can also be seen in response to the survey's questions about whether advocates for educational technology have oversold it.

About half (49 percent) of faculty members surveyed disagreed that "using digital tools" -- in both in-person and online settings -- "ca n lower the per-student cost of instruction without hurting quality," and about two-thirds agreed that administrators and vendors "exaggerate the potential financial benefits" of instructional technology (63 percent) and "play down the risks to quality" posed by it (70 percent). There was little difference on these questions between those who had and had not taught online.

n lower the per-student cost of instruction without hurting quality," and about two-thirds agreed that administrators and vendors "exaggerate the potential financial benefits" of instructional technology (63 percent) and "play down the risks to quality" posed by it (70 percent). There was little difference on these questions between those who had and had not taught online.

Half of digital learning leaders agreed with the statement about vendors and administrators exaggerating the potential financial benefits (perhaps a moment of self-criticism), but otherwise the administrators included in the survey take a much more favorable view of online education and instructional technology.

More than half of digital learning leaders (51 percent) believe digital tools can lower costs without harming quality, and nearly 90 percent of digital learning leaders agreed that online courses can produce equivalent student outcomes to face-to-face classes.

In contrast to faculty members, more than three-quarters said that online courses were at least as effective as face-to-face classes on the entire range of attributes. Their biggest question was on the ability to reach at-risk students, where only 20 percent said online courses were more effective, and 25 percent said they were less effective than in-person classes.

Griffiths of SRI noted the "almost Pollyannish" views of digital learning leaders, saying she suspected they may be so accustomed to being "evangelists" amid faculty opposition that they may have trouble shutting that down. "It's important to have reservations and ask hard questions about who [online learning] is good for and what it’s good for," she said.

Support, Incentives (and the Lack Thereof)

The survey results provide a mixed picture on why faculty members might be choosing to teach online, and what they are gaining from it.

A strong majority of those who have taught online, 71 percent, say doing so has helped them develop skills and practices that have improved their teaching both online and in person. More than seven in 10 say online teaching has enabled them to think more critically about how to engage students with content, better use multimedia content and better use the learning management system. Roughly half say they are more comfortable using active learning and project-based learning techniques and better at communicating with students outside class.

"It's significant, and heartening, that faculty are maybe tweaking, re-engaging in their methodologies, because of their experience in teaching online," said Jill Buban, senior director of research and innovation at the Online Learning Consortium. "I like that some of them are having an aha moment because of teaching in an online modality."

Over 90 percent of online instructors said they had been involved in designing their courses, but less than half said they had received training to do this, and just under one in four said they had worked with instructional designers. The clear majority (89 percent) said their online courses were asynchronous, meaning that students complete course work and interact with instructors on their own schedule.

Professors were asked to assess the degree of training and other support their institutions offered to improve and encourage their use of digital learning.

Solid majorities agreed that their college or university provides adequate technical support for creating (54 percent) and teaching (57 percent) online courses -- roughly one in five disagreed on those points.

Beyond that, though, the reviews are likely to disappoint campus leaders. Fewer than a third agreed that their institution "appropriately rewards contributions made to digital pedagogy" (32 percent), "rewards teaching with technology (in-person or online) in tenure and promotion decisions" (27 percent), compensates fairly for developing online courses (27 percent), acknowledges time demands for online courses in their workloads (30 percent) and provides monetary or other incentives for teaching online (20 percent).

And as seen in the chart above, their perceptions have improved since last year on some of those matters, but worsened on others. (The data have changed little over five years of Inside Higher Ed surveys, in fact: in 2013, 36 percent of professors agreed that their institutions rewarded contributions to digital pedagogy, which slipped to 32 percent this year.)

The faculty perspectives are at odds with digital learning leaders at their institutions on most of these questions, although the administrators acknowledged shortcomings on the nonfinancial rewards for professors to use technology in teaching.

Phil Hill, co-publisher of the blog e-Literate, said he felt institutions should be doing a lot more to support faculty members who are teaching online, by providing more professional development, greater assistance from instructional designers and more data and feedback on teaching

“The needle seems to be moving on faculty receptivity to teaching online,” he said. “The field is becoming more receptive to technology-enabled teaching and its possibilities, but we’re doing a terrible job in North American higher education in supporting them.”

Hill said the finding that teaching online helped many faculty members improve their teaching in person pointed to “a huge opportunity to improve teaching and learning,” but noted that this seems to be happening “in spite of institutional support, not because of it.”

Luke Dowden, director of the office of distance learning at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, drew attention to the finding that many faculty members look to their peers to decide whether or not to adopt new technologies, and said institutions should create formal mentoring networks or find faculty champions to support this. “Change really takes off when faculty talk to each other,” said Dowden.

Dowden said that the small proportion of professors reporting that they have worked with instructional designers was disappointing, given how much that field has grown in recent years.

“It troubles me that only 23 percent of faculty have worked with institutional designers,” said Dowden. “It could be an access issue, but this is something we should highlight. The challenge to digital learning leaders is ensuring that faculty have access, and that they know they have access.”

Assessing Assessment Efforts

Professors remain skeptical about the value of technologies aimed at understanding and measuring how much students on their campuses are learning, although support for the efforts appear to growing.

Nearly six in 10 instructors question the motivations for the assessment efforts, strongly agreeing (30 percent) or agreeing (29 percent) that they "seem primarily focused on satisfying outside groups such as accreditors or politicians." (That's down from 65 percent in 2016.)

They are split down the middle on the question of whether assessment efforts have helped increase degree completion rates and the quality of teaching and learning at their institutions, with roughly 37 percent and 36 percent agreeing to each and a comparable share disagreeing. This also represents a meaningful change from last year, when barely a quarter agreed with those assertions.

Campus efforts to give faculty members a sense of ownership in assessment initiatives appears to be working. Nearly half of professors (47 percent) agree that "faculty members at my institution play a meaningful role in planning for the use of these assessment tools, and 43 percent say there is "meaningful discussion at my college about how to use the assessment information." Those percentages are up from 37 percent and 35 percent, respectively, in 2016.

But college leaders may be falling down on the job on the most important part of the equation: giving instructors the data they need to change how they teach or students learn. Just 30 percent of professors say they "regularly receive data from my college -- gathered through these assessment efforts -- that allow me to improve my teaching." Tenured professors take a particularly dim view on this question (and others on assessment), with just 23 percent saying they get useful data.

Use of Digital Courseware and Open Resources

This year's version of the faculty technology survey included an expanded set of questions about the nature of the content used in online and blended classrooms.

A third of faculty members said their courses had used digital courseware, software that delivers instructional content that can be customized and adapted to work across different types of learning environments. Seventy percent of those instructors said the courseware they used had "adaptive or personalized learning tools or functionalities."

Nearly two-thirds of instructors (62 percent) said they were involved in the selection of digital courseware when creating an online or blended class, but most of them appear to be doing so in an ad hoc way.

Barely a quarter (28 percent) said their institution had a formalized process for evaluating such software, and more said they learn about the effectiveness of such tools from recommendations from colleagues (83 percent) than from any other source, followed by discussions with vendors (52 percent), vendor marketing materials (36 percent) and peer-reviewed academic publications (35 percent).

Faculty respondents overwhelmingly (93 percent) said they believed that course materials were too expensive, that instructors should make price a "significant concern" when assigning course readings (82 percent), and that professors should assign more free open educational resources (90 percent).

Buban, of the Online Learning Consortium, said she was heartened that instructors generally felt like they were able to choose their courseware, rather than it being foisted on them from the "top down." But more institutions should probably be creating more formalized processes to ensure that instructors are getting good, accurate information, rather than depending excessively on vendors or the perspectives of individual faculty colleagues.

Wariness of Commercial Providers

Colleges and universities are increasingly using companies (called online program management, or OPM, providers) to take their academic programs online. But the surveyed faculty members and digital learning leaders alike would prefer to limit the companies' role.

Fifty-seven percent of faculty members and 51 percent of administrators said that colleges should not work with OPMs, instead developing their own courses in house. Almost all the rest said that OPMs should be hired to handle back-end functions only, allowing colleges to retain control over course development and admissions. Just 5 percent of faculty members and 4 percent of administrators said that institutions should hire OPMs to develop, produce and manage their online courses.

Given the poor perception of OPMs among faculty members and administrators, it is unsurprising that both groups were not particularly enthused about the benefits of outsourcing online course tasks. Just 18 percent of faculty and 28 percent of digital learning leaders felt that outsourcing could improve the quality of their courses. A larger proportion of faculty members and administrators believed that outsourcing would lighten the workload at their institution.

James Wiley, a principal analyst at Eduventures, a consulting firm, said the results were “not encouraging news” for commercial providers. “It seems there is not a whole lot of trust out there around the world of ed tech and its value.”

Here are other findings from the survey:

- More than 60 percent of faculty members and digital learning leaders agreed that all digital materials created by colleges, even those not for specific courses, should be compliant with the Americans With Disabilities Act. (The question was prompted by the U.S. Justice Department's demand this year that the University of California, Berkeley, make all publicly available digital content compliant with ADA requirements.) Almost all faculty members (93 percent) said the courses at their institution are already ADA compliant. Sixty-four percent of faculty members said they received training on how to make course materials ADA compliant, including 67 percent at public institutions, and 46 percent at private institutions.

- Three-quarters (76 percent) of faculty members said they did not believe undergraduate students have a "sufficient understanding" of what plagiarism is. Roughly half (48 percent) said they required undergraduates to submit papers through plagiarism detection software, and most agreed that the software detects "most" (55 percent) or "some" (37 percent) instances of plagiarism. More professors disagreed (46 percent) than agreed (27 percent) with concerns about antiplagiarism software voiced this year in a "manifesto" published in Hybrid Pedagogy.