You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

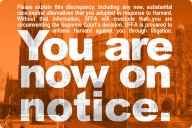

Our Lady of Mercy High School

Wikipedia

Lola DeAscentiis was a senior this year at Our Lady of Mercy School for Young Women, in Rochester, N.Y., and had her heart set on attending the University of Pennsylvania.

Lots of talented students want to attend Penn, and the university rejects tens of thousands of students who are bright and could do the work. But DeAscentiis had very strong grades and a range of activities.

DeAscentiis applied early to Penn—and was rejected shortly after a teacher at Mercy revoked a letter of recommendation. The original letter said, “She excels at applying classroom knowledge to real world experiences, which greatly distinguishes her from her peers” and called DeAscentiis a young woman of “piety, compassion and integrity.”

But the teacher sent a subsequent letter saying she was withdrawing the first letter because DeAscentiis “breached ethical conduct, broke confidentiality, and betrayed trust.” She did not say how.

As first detailed in an article in Rochester City Newspaper last week, the controversy didn’t end there.

Emily Cady was DeAscentiis’s college counselor, and she was shocked by what had happened. She said DeAscentiis was among her best students.

She told administrators at Mercy that they should tell DeAscentiis or her parents about the letter being revoked. They said they would do so by Christmas but did not do so. Then they told Cady during the holiday break that they would not be doing so. And Cady found out that the teacher had also sent a similar retraction of her recommendation to DeAscentiis’s next choice, Wellesley College.

What Happened?

DeAscentiis and her family, and Cady, told City that they believe the teacher’s view of DeAscentiis changed after an email mess-up.

In October, DeAscentiis said, Caroline Kurzweil (the teacher) had told her to attend an afternoon meeting for the school’s literary magazine. DeAscentiis had plans to mentor a younger student that day and told Kurzweil they needed to choose a different time. DeAscentiis said that Kurzweil then canceled her mentoring session and demanded she show up to the magazine meeting.

DeAscentiis attended.

The next day, Kurzweil sent DeAscentiis an email. The email began, “Sometimes an editor needs to be more than a little flexible with schedules ... as you experienced yesterday.”

DeAscentiis forwarded the email to a confidant and added the line, “Just thought I’d share, lolz! I just love the way this email begins.”

Accidentally, she also forwarded the email to Kurzweil.

Kurzweil did not respond to a request from Inside Higher Ed for a comment. Kurzweil also declined to speak to City.

The principal, Martin Kilbridge, did send an email to Penn that said he believed Kurzweil was not truthful about the administration’s investigation.

“Ms. Kurzweil misrepresents my understanding of the events that transpired, implying that I support her determination to retract her recommendation,” Kilbridge wrote. “Her account is a gross distortion of reality and a travesty.” He wrote, “Lola is a shining star and does not deserve to have her character tarnished by what I can only conclude is personal animus.”

Kilbridge has since left for another position.

The Resignation Letter

On Dec. 29, Cady resigned.

“Professionally, I’ve been in this field for 20 years. I’ve never experienced anything like this,” she said in an interview with Inside Higher Ed.

She does believe teachers have the right to decline to write a letter or to withdraw a letter they have written for a student. But she said that in her career, maybe four or five times, she’s been involved in such situations. Never was the issue as basic as the one in DeAscentiis’s case. And she remembers, in these cases, there were meetings involving several people before a letter was withdrawn. (Some colleges in fact are questioning the fairness of recommendation letters generally, because at a private high school like Mercy, the teachers and counselors have more time to craft a good letter.)

Cady is sure, however that DeAscentiis was treated unfairly.

“From my perspective, there was absolutely no reason” to send Penn a revocation of this letter, Cady said.

In her resignation letter, she wrote, “I was told that the final decision had been made, apparently on the advice of legal counsel, not to disclose the inappropriate acts of the staff member. I was told that non-disclosure was the best decision for the institution. I disagree.”

She continued, “Mercy’s motto, Via Veritas et Vita (the Way, the Truth, and the Life), has been the foundation of my daily work with students, colleagues and families since joining this institution. As the director of counseling and wellness, I rely on a bedrock of trust in order to guide young women to be ‘pioneers of change.’ In my six years at Mercy, I have earned that trust day by day, interaction by interaction, relationship by relationship.”

Cady wrote to the principal, “Because you have refused to inform this student or her parents of this situation, because you have allowed a teacher who intentionally undermined a student’s college admissions process to remain in her position, because you have not demonstrated a clear process to ensure that this does not happen again, regrettably, I can no longer in good faith continue in this position. I resent having to choose between my integrity and my livelihood, but only one will allow me to sleep at night. Ethically and morally, we are not aligned—and that is truly heartbreaking.”

The letter was intended to be confidential. But someone made copies for Mercy employees to whom it was not addressed. Cady provided a copy to Inside Higher Ed after it had already been distributed by someone else.

Other Perspectives

Inside Higher Ed reached out to national leaders and others on admissions for their perspectives.

David Hawkins, chief education and policy officer for the National Association for College Admission Counseling, said it was “rare that a teacher or other recommender would retract a letter of recommendation, particularly in the absence of a formal action on the part of the school’s administration, such as a disciplinary action against the student.”

He added that NACAC advises schools to “have written policies to guide administrators and staff through actions that could affect students’ college applications.” NACAC also believes these policies should be shared with students and their families. “In addition, individuals employed by the school generally should not take unilateral action given that they are in the employ of the school, but should coordinate with others—particularly the school counselor and administrators—as to the nature of the individual’s concern to come to a resolution that is formally backed by the school itself.”

Melanie Gottlieb, executive director of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, said, “We train admissions counselors and leaders to keep the well-being of the student at the center, and that transparency is crucial to the staying true to that principle while honoring institutional integrity. A policy that informs the applicant when a letter has been rescinded is important for transparency.”

David Carro, whose last day as vice president of external relations at Mercy was Friday, released this statement: “The article is not fully accurate from Mercy’s perspective, nor is it wholly representative of the incident or our school. We were bound by confidentiality of those involved in the incident and did not share private details on the situation with the publication, nor will we do so. Following this incident, a new policy has been put in place to ensure a smooth process for collegiate academic letters of recommendation and will be in effect at the start of the new school year.”

He declined a phone interview.

A spokesman for the University of Pennsylvania declined to comment.

A Happy Ending?

The story has a sort-of happy ending.

After Penn rejected her, DeAscentiis quickly applied to more colleges. Cady helped her, as did teachers (other than Kurzweil) with recommendations.

In April, she was admitted to Harvard University. She’ll enroll this fall.