You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The University of California at Berkeley is drawing praise for its decision to share how often it has granted access to email and other forms of electronic communication created by students, faculty members and staff at the institution.

The university earlier this year released its first transparency report, showing how many times since January 2014 the institution has received what are known as “nonconsensual access requests.” UC-Berkeley says it is the first university to release such a report, according to The Daily Californian.

“Berkeley is historically an institution that has valued privacy in order to foster a climate where academic debate can thrive,” William Allison, director of architecture platforms and integration, said in an email. He said the report contributes to “setting the bar for higher education in our transparency and accountability in handling people's information, and in increasing awareness and an expectation of privacy in our community.”

In most cases, students, professors and other employees have to give their consent before the university can give a third party access to records of their electronic communications. The Electronic Communications Policy at Berkeley outlines four main limitations to those privacy protections.

For example, the university can be required by law to grant access, or decide to do so in the face of evidence suggesting the record holder broke the law or violated university policy. The university may also grant access in light of “compelling circumstances,” such as if not doing so could lead to “bodily harm, significant property loss or damage, loss of significant evidence of one or more violations of law or of university policies,” or if there isn’t enough time to obtain consent.

In cases not covered by the policy, such as if the record holder has left the university or died, the institution “still seeks to limit access to only the minimum amount of information necessary,” according to university policy.

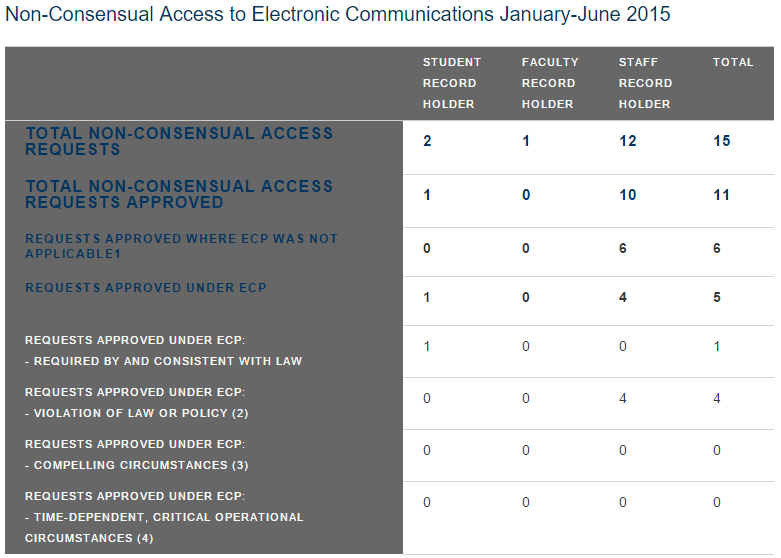

Between January 2014 and June 2015, the university received 51 nonconsensual access requests, the report shows. The university approved 41, 18 of them for time-sensitive reasons.

Only once since 2014 has the university granted access to a student’s records, and then only because it was required to by law. UC-Berkeley never used compelling circumstances as a reason to grant access to records.

Elana J. Zeide, a privacy research fellow at the New York University Information Law Institute, said the information in the report isn’t “earth-shattering,” but that releasing it “is a fantastic step toward creating more transparency.” She said she was not aware of other colleges having released similar reports.

“The report itself indicates that Berkeley is paying attention to how it handles potentially sensitive information about students, faculty and staff -- not recklessly sharing information, but instead using a protocol to consider whether it is appropriate to share information under certain circumstances,” Zeide said. “It also shows the relatively small scope of sharing of educational data without consent -- a very small number of instances compared to the number of individuals and records held by Berkeley.” (Last year, the university enrolled more than 37,000 students and employed 1,620 full-time faculty members.)

Outside of higher education, transparency reports have been used to give the public insight into how often companies receive and respond to requests for information about their users from governments, often made as part of investigations into criminal cases. It is a fairly new practice; Google, for example, released its first transparency report in 2010.

Since the National Security Administration leaker Edward Snowden in 2013 revealed details about the U.S. government’s extensive surveillance efforts, more companies have started sharing information about government requests and how user data is stored. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter now release regular reports, as do retail giant Amazon and apps such as Snapchat and WhatsApp.

Allison said the university was influenced by those and other companies to produce its own transparency report. “Privacy has to begin at home, so to speak, and so I wanted students, faculty and staff to be able to understand how we protect their information, and why that's important,” he wrote.

Tracy B. Mitrano, a former director of IT policy at Cornell University (and a blogger for Inside Higher Ed), said corporations publish transparency reports mainly to reassure customers that their personal information is handled responsibly.

For colleges, Mitrano said, transparency “goes straight to our mission. We’re not doing it to maintain our profit motive. We are doing it to demonstrate … that privacy goes to the core of our autonomy and ability to operate with free speech and open inquiry.”

Both Mitrano and Zeide connected transparency reports to the broader issue of privacy in higher education. They recommended that more universities follow UC-Berkeley’s example of disclosing the number of requests received and approved.

“Much of today's debate about student privacy stems from a lack of transparency about who has access to education data and why,” Zeide said. “We need more of this kind of transparency for higher ed stakeholders to trust universities with very intimate information as schools collect an increasing array of data beyond academic matters.”