You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Average per-student subsidies were generally higher for low-income students than high-income students, according to a new report.

Brookings Institution

A report being released today pushes back against the idea that state subsidies lowering tuition at public four-year universities disproportionately benefit students from wealthy families.

The research, being released under the Brookings Institution’s series of Evidence Speaks reports, finds appropriations from state and local governments used to offset educational costs at public institutions are smaller for students from higher-income families than for those with lower incomes. It also makes the case that low-income students are well represented across types of public four-year universities, including very selective universities, where they represent a quarter of enrollments -- a far higher proportion than is the case at most elite private universities.

That might not be surprising to those who expect public higher education to focus on affordability and accessibility. But the findings run counter to an argument that has been growing in recent years among commentators and analysts, said Jason Delisle, a resident fellow in education policy studies from the American Enterprise Institute. Delisle wrote the new report along with Kim Dancy, a policy analyst in the Education Policy Program at New America.

“You have to be almost in this echo chamber of the D.C. policy world in order for this to be a big finding,” Delisle said. “An argument that I hear a lot, and that other people hear a lot in the policy community and D.C. and even in elite newspapers like The Washington Post, is that the taxpayer subsidies for public universities go disproportionately to high-income students.”

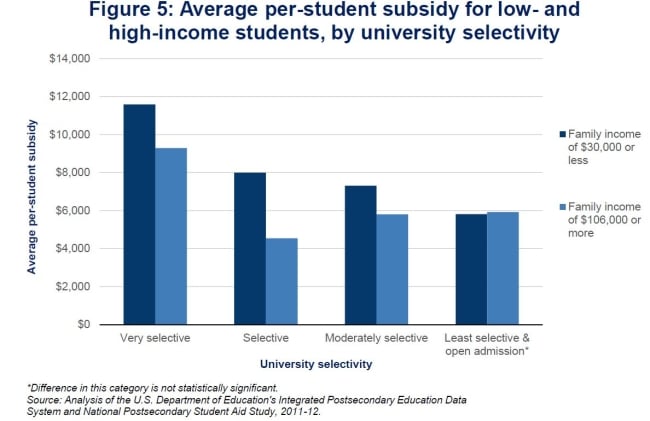

The basic argument Delisle and Dancy sought to test starts with the idea that states shell out larger appropriations to their top public universities than they do to their less competitive institutions that enroll higher levels of low-income students. Those universities in turn enroll more students from high-income families, and they spend more per student. At the same time, less selective schools draw a higher percentage of their students from lower-income backgrounds while receiving less in appropriations and spending less per student.

The New York Times Magazine ran an article in 2015 that summarized the theory this way:

“Flagship public universities -- like the University of California, Berkeley, or the Universities of Michigan and Virginia -- often behave like elite private schools, using aid to attract the best students, typically the ones who would probably go to a decent school without government support.

“That means that high-achieving students from educated families receive a disproportionate share of financial assistance, while those at the bottom, struggling students from families ill equipped to support their educations, receive a disproportionately small share.”

In 2014, The Washington Post’s editorial page editor, Fred Hiatt, likened state support to a subsidy for the rich.

“States across the country subsidize higher education for their residents by paying the difference between in-state tuition rates and what a college education really costs,” he wrote. “This is so much a part of the American fabric that few stop to think about its regressive aspect.”

But Delisle and Dancy came to a different conclusion. They merged 2011-12 data sets from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study and Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System to generate a look at public university spending on educational services and how much students pay toward those costs. They then used the data to measure indirect subsidies -- appropriations from state and local governments and other revenue sources that offset educational costs -- by comparing the difference between university spending and charged tuition.

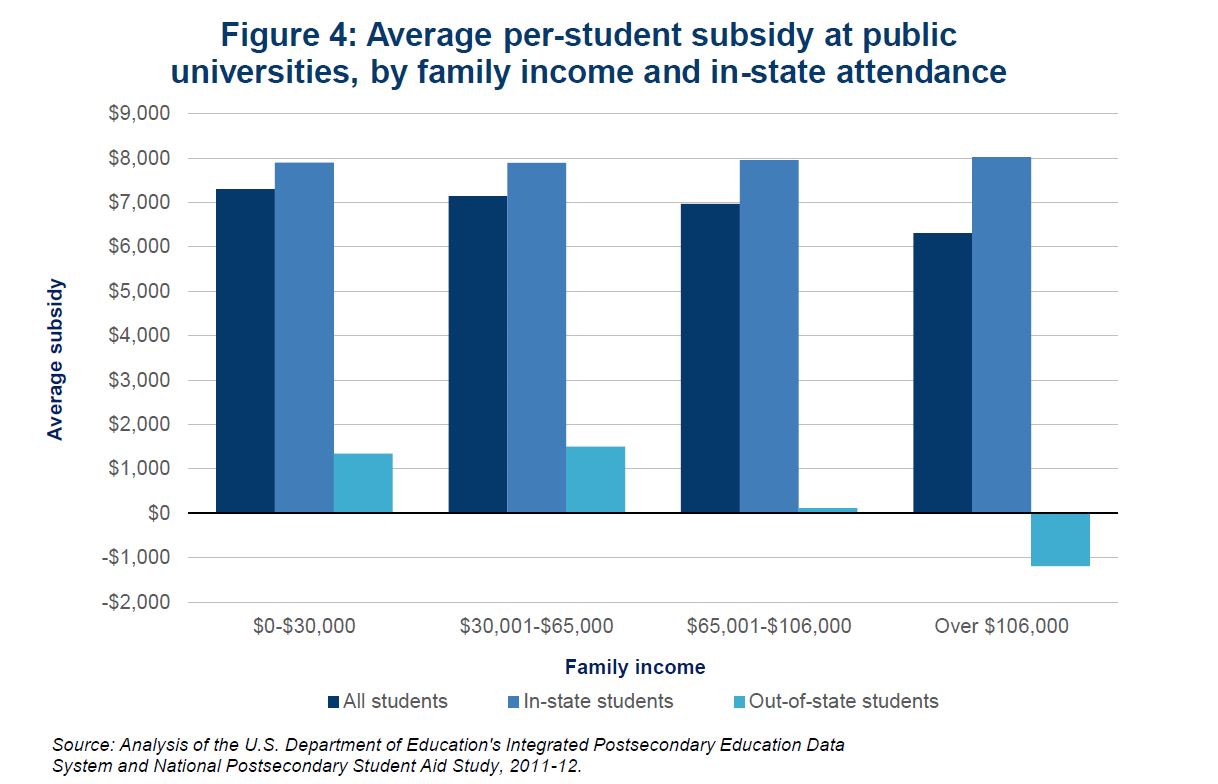

The results show that the national average indirect subsidy is highest for students with lower incomes. The average student reporting a family income of $30,000 or less had subsidies of $7,305. The average student with a family income of more than $106,000 had a subsidy of $6,318.

In addition, the report says differences in out-of-state and in-state tuition contribute to the differences in subsidies for income groups. High-income students are much more likely to attend out-of-state institutions, the report said. In doing so, many forgo government subsidies. Students from the wealthiest backgrounds actually averaged a negative subsidy, meaning on average they paid more tuition than universities spent on education services, even after factoring in scholarships and aid.

“What you have is essentially rich students opting to pay three times as much as the in-state rate,” Delisle said. “That frees up a bunch of resources for universities to keep tuition low for in-state students.”

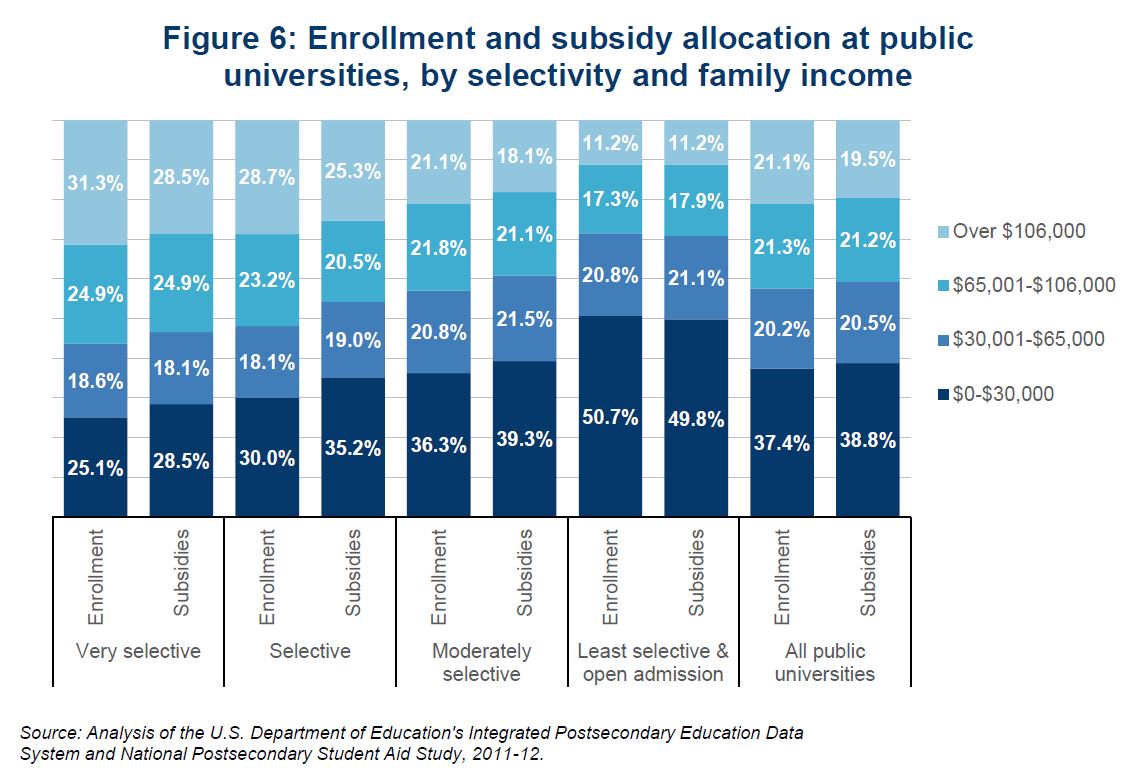

Delisle and Dancy also looked at how government subsidy levels compared to enrollment levels at different types of institutions. They found that low-income students received slightly more in subsidies than they would if subsidy dollars were divvied up based on enrollment portions. Students with family incomes of $30,000 or less were 37.4 percent of enrollments at public universities across the country but received 38.8 percent of indirect subsidies. In contrast, students with family incomes above $106,000 were 21.1 percent of enrollments but received 19.5 percent of subsidies.

The rule held nearly across the board when splitting universities up by selectivity levels -- students in the lowest income bracket made up 25.1 percent of enrollments at very selective institutions but received 28.5 percent of subsidies. The only exception was at universities deemed least selective and those that had open admission, where the lowest-income students made up 50.7 percent of enrollments yet only received 49.8 percent of subsidies.

The report calls indirect subsidies “relatively flat, if not slightly progressive.” It indicates that, in general, most financial aid appears to be allocated based on need, said Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University whose specialties include finance and student aid.

“It’s a set of results that are counterintuitive, in that the general perception is that higher-income students are getting much larger subsidies,” said Kelchen, who reviewed a draft of the research earlier this year. “And that may be true at the most absolute, most selective flagship institutions. But what the paper shows well is that higher-income students disproportionately attend private and out-of-state colleges, and the socioeconomic mix at most public colleges is more representative of America.”

However, the results still show that very selective institutions enroll lower portions of low-income students than other types of institutions. And some wondered whether it is ideal to have parity between the percentage of students in an income bracket and the percentage of state subsidies going to those students.

“Should that subsidy be even close?” said José Luis Santos, vice president for higher education policy and practice at Education Trust. “I would expect low-income students, because they have a higher need, to get a bigger subsidy.”

Percentages don’t express the differences in real dollars that students feel, he said. So although the 25.1 percent of students at very selective institutions from low-income families may be getting 28.5 percent of the universities’ subsidies, they may still be facing more financial pressure than wealthier students.

“They are attending very selective institutions and paying higher tuition and fees,” he said. “There’s still a gap there in what they have to be able to cover.”

The report says that the way subsidies should be allocated is open for debate.

“We’re sort of agnostic in this report about how the subsidies should be distributed and what the right percentage of enrollment is,” Delisle said. “We mainly point that out simply to help explain why high-income students are not getting a disproportionate share of benefits.”

Delisle and Dancy also ran their numbers after expanding their measure of indirect subsidies to include both spending on education services and other activities including research. They found low-income students receive smaller subsidies when research dollars are included. Those from families with incomes of $30,000 or less received subsidies of $13,780, while those from families with incomes over $106,000 received subsidies of $15,972.

“Research spending does correlate to income, actually,” Delisle said. “It is some strange thing going on there, where high-income students are in some way sorting themselves for the institutions that spend more on research.”

The data come with several important limitations. They represent national averages, not estimates on the state level. That would obscure variations from state to state. Some state systems may still fit the narrative that high-income students are receiving more in subsidies. The data also do not include community colleges.

Delisle also pointed out that the research is for a single year. He would like to do more work to see how the data change over time.