You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

LYNCHBURG, Va. -- Jerry Falwell Jr. stood on a stage at Liberty University one recent Wednesday and delivered a winding introduction.

It was convocation, one of the evangelical Christian university’s slickly produced thrice-weekly assemblies mixing prayer, well-known speakers and entertainment. Thousands of students are required to attend, and the assemblies are broadcast online.

Falwell, Liberty’s 6-foot-2, 55-year-old president, took the stage after a song and a prayer. He told students Liberty would give them an extra pass to skip a convocation -- known informally as convo -- if 2,500 of them registered to vote. He also introduced the day’s speaker, comedian Jeff Foxworthy.

“Like me, he’s got an old bulldozer, and instead of playing golf -- I’ve never played golf in my life, I’m a Campbell County redneck, I grew up in Campbell County, and my dad grew up in Campbell County, and his dad, and his granddad -- anyway,” Falwell said. “But my old bulldozer, that’s what I do for recreation. I get on that and push trees over. I build trails, four-wheeler trails off into the woods. I’ve probably got 20 miles of trails now. And, so, um, when I wear a suit, it’s a little bit deceptive, because I’m a redneck at heart.”

This mash-up of religion, technology, politics, cultural identity and celebrity has come to define Jerry Falwell Jr. and the suddenly powerful university he has led for a decade. But neither president nor university found the right mix immediately -- both were stranded in proverbial deserts before stumbling upon successful strategies.

Liberty struggled to stay afloat for years until its online program started to take off in the mid-2000s. Since then, it has vaulted to new heights and can call itself the largest private, nonprofit university in the nation and the largest Christian university in the world.

Falwell, meanwhile, worked behind the scenes to keep Liberty alive as it struggled to grow and as his prominent father, the late Reverend Jerry Falwell Sr., held the university’s top leadership position. That changed in 2007 with the elder Falwell’s death. Nine years later, the younger Falwell vaulted himself into the national spotlight during the 2016 presidential campaign by becoming an early endorser of Donald Trump.

Since then, Falwell has stuck by Trump during his darkest hours, defending the candidate and then president amid racial controversy and sexual assault allegations. In doing so, he has broken the mold for a university president’s involvement in politics, invoking fierce criticism on moral and organizational grounds.

Yet Falwell’s risky political play has yet to stop Liberty’s climb. The numbers clearly show increasing fortunes for both Liberty and its president. In the fall of 2007, the start of Jerry Falwell Jr.’s first year leading Liberty, the university enrolled just over 27,000 students, according to federal data. Today, it enrolls more than 110,000, with about 15,000 attending its campus here and the rest studying online.

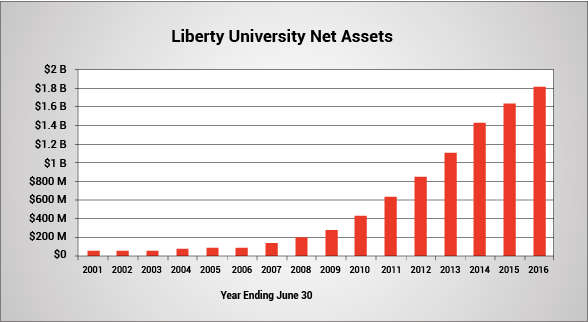

Liberty’s net assets, measured in the tens of millions of dollars a dozen years ago, exceeded $1.8 billion in 2016. Next year it will move to the top division in college football, realizing a key vision of Jerry Falwell Sr. by becoming the evangelical equivalent of the University of Notre Dame or Brigham Young University -- a nationally recognized religious institution of higher learning that uses its football program to capture hearts and minds on national television.

Essentially, Falwell and the university have won all of their battles -- from the struggle to survive and thrive to the fight for political prominence. But Falwell isn’t done fighting yet. And the question now is where the president and university go from here.

A Family Education

In many ways, Jerry Falwell Jr. is the product of his father’s education. He remembers traveling around the country as a young boy with Jerry Falwell Sr., helping to sell books and sermons on vinyl records. In one story, the elder Falwell forgot to give his son the key to a cash lockbox at the book table. The 7-year-old Jerry Jr. kept the product moving anyway, stuffing money in his socks and down his shirt.

He attended two educational institutions his preacher father founded: the former Lynchburg Christian Academy, a pre-K-12 school now known as Liberty Christian Academy, and Liberty Baptist College, graduating from the college that would soon become Liberty University with a degree in religious studies and history in 1984. Falwell then continued on to earn his J.D. from the University of Virginia School of Law.

Liberty’s biography of Falwell says he went into commercial real estate development, represented local clients and returned to Liberty to become general counsel in 1988. That chain of events misses a formative disagreement between Falwell and his mother, Macel, though.

During his years in law school, Falwell started to date Becki Tilley, the woman who would become his wife. But his mother didn’t approve at first.

“She had a certain type of girl picked out that she wanted me to marry, and I didn’t want to marry that kind of girl,” Falwell said during a recent interview. “She didn’t like the fact that Becki wasn’t one of these girls that gets up on stage and sings and has a lot of makeup on and all of that stuff. She’s just kind of a country girl.”

The disagreement led to Falwell’s mother telling him she wouldn’t pay his bills. So he lived on his savings account for two years.

“That’s why I went into real estate developing, because I was determined to make my own money so nobody could tell me what to do,” Falwell said.

Falwell can still tick off the details of some of his successful early real estate deals, explaining in sequence the way parcels of land changed hands for escalating prices. On the other end of the spectrum, he counts as his worst deal the purchase of a Western Steer steak house and buffet restaurant.

The restaurant was fine until a competitor opened next door. Then the property struggled to make money until Falwell eventually flipped it for other land he could develop, leaving him with bad memories of owning a restaurant.

“You can’t do anything with it,” Falwell said. “Either people walk in the door or they don’t. It’s just that simple.”

The same can’t be said of universities. They recruit students, start programs and conduct research. Universities also court donors, erect buildings and play sports.

But when Falwell started as Liberty’s general counsel, much of his time was dedicated simply to keeping the institution alive. Jerry Falwell Sr. founded Lynchburg Baptist College in 1971, and in its early years the institution’s primary source of revenue was donations from the preacher’s television ministry, according to an account in Macel Falwell’s 2008 book, Jerry Falwell: His Life and Legacy. High-profile televangelist scandals hit donations hard in the late 1980s, and the university was staring at $82 million in short-term debt. It missed paydays for faculty at times.

The situation would play out repeatedly over the years. Liberty’s accreditor, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, placed the university on probation multiple times in the 1990s because of heavy debt loads. In 1990, the university’s debt totaled $110 million. In 1996, debt totaled $40 million and scheduled payments to bondholders had been late for two years.

“The financial situation has impinged on the education program,” Jack Allen, associate executive director for the SACS Commission on Colleges, told Christianity Today in February 1997.

Major donors helped to keep Liberty afloat. So did Jerry Falwell Jr., whom relatives and acquaintances describe as a quiet, almost reclusive behind-the-scenes worker during those years.

“He would spend the weekends trying to cover the payroll that they sent out on Friday,” said Becki Falwell, whom Jerry Jr. married in 1987. “It was difficult. It was very stressful.”

Steven Snyder is an attorney in Greenville, S.C., who attended Liberty and law school with Falwell. Snyder said Falwell would put in 90 or 100 hours a week at times after he started working at Liberty.

“The worst times were in the 1990s,” said Snyder, who joined Liberty’s Board of Trustees in 2014. “I know there were plenty of times where they were down to a few days if they were going to make payroll. There were times when they wondered if the school would still be open in a month.”

Liberty and the Falwells survived the financial struggles. In the late 1990s, the university was formally separated from the other divisions of Falwell Ministries, like Thomas Road Baptist Church. That was a change from the way things had evolved after the senior Falwell founded the church in 1956, said John Borek, who served as Liberty’s president from 1997 to 2003 and has been called one of Jerry Falwell Jr.’s mentors

“It was very similar to other businesses -- it grew and it had different offshoots,” Borek said. “As time went on, we asked, why don’t we spin off one thing or another, because it needs to become self-sustaining or it has its own vision that needs its own finances. Liberty just flat out became more.”

Then in May 2007, the Reverend Jerry Falwell Sr. died at the age of 73.

‘We’re Actually Going to Have Some Financial Prosperity Here’

After his death, the preacher’s two sons took over the large enterprises he founded. His elder son, Jerry Falwell Jr., became Liberty’s leader. The younger, Jonathan Falwell, led Thomas Road Baptist Church.

Jerry Falwell Jr. had been fearing his father’s death for years. In addition to the personal loss, it meant taking over Liberty’s pulpit. As Liberty’s vice chancellor and general counsel, the younger Falwell was able to run the school behind the scenes while his father, who was still the university’s public leader with the title of chancellor, handled the public-facing responsibilities. But Jerry Falwell Jr. eyed the public-speaking responsibilities of a university president with dread.

“I grew up in a fishbowl, because Dad had a huge church and he started a school and he got a lot of publicity,” he said. “I just got burned out on it.”

But Liberty’s board named Falwell his father’s successor. For several years, he dealt with nerves for days before he had to speak publicly. He was also uncomfortable with the responsibility of making appearances at the university’s many events.

As for Liberty’s operations during the transition, Falwell saw his biggest challenge as cohesiveness. He needed to keep the university running smoothly while showing that Liberty was bigger than one man.

“Dad was such a charismatic leader that there was a lot of concern in those days whether the school was completely dependent on his personality,” Falwell said. “He was always out there in the public, just -- he didn’t have -- he never met a stranger. He was just always -- and he built it from scratch. So that was a real concern.”

Liberty’s fortunes began to improve. Many of its debts had already been whittled down thanks to donations and lender forgiveness. But the late Jerry Falwell Sr.’s life insurance policy, valued at $34 million, allowed the university to pay off its debt and start building an endowment.

At the same time, the university’s online programs were taking off. Since Falwell Jr. took over, on-campus enrollment has jumped from 9,600 to more than 15,000, according to the university’s biography of the president. Online enrollment has grown from 27,000 to more than 94,000, and Liberty calls itself the fifth-largest university in the country.

The university traces its online operations back to 1985, when it started a distance learning program by mailing VHS tapes to students. Jerry Falwell Jr. described the program as limping along for 20 years, even as Liberty improved its academic quality. Then around 2005, high-speed internet connections started to take hold. Liberty found itself positioned to serve an enormous adult population with its online offerings.

In 2009, Falwell came to a realization: the online program had reached the point where Liberty was no longer struggling to survive.

“I’d learned to manage debt,” Falwell said. “I’d learned to negotiate with creditors. I would spend a lot of weekends on the phone with lenders and donors trying to find money to cover the paychecks that had gone out the Friday before. That’s how close to the edge we were. Then it hit me all of a sudden. When I saw the online program really just taking off, I was looking at the balance sheet and I said, ‘I can’t believe this. We’re actually going to have some financial prosperity here.’”

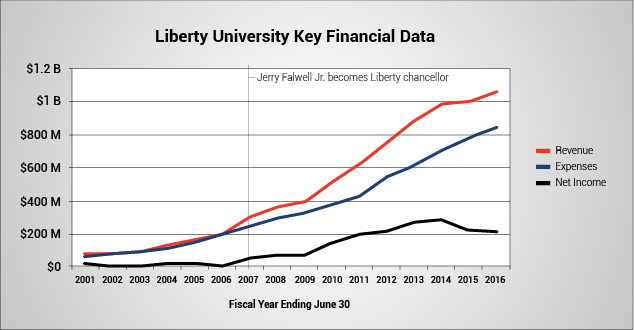

In 2005 Liberty posted net income of $12.1 million on revenue of $162.6 million, according to federal tax filings. By 2016 its net income was $215 million. The university’s annual revenue eclipsed $1 billion in 2015.

The university’s net assets have grown from about $150 million in 2007 to more than $1.8 billion in 2016.

Jerry Falwell Jr. has prospered as well. In 2007-08, his first full year leading Liberty after his father’s death, he received about $206,000 in compensation from the university and its related entities. In 2015-16, his compensation totaled just over $985,000.

Conservatism and Christianity in Action

Today, Falwell’s speaking style contrasts sharply with that of his late father. Whereas the elder Falwell was every bit the Baptist preacher, filling rooms with crisp delivery and a golden voice, his son speaks in a resonant, wandering mumble. The stream-of-consciousness style nonetheless holds attention. It projects a comfort on stage that belies the fact Falwell was terrified of public speaking for much of his life.

In person, Falwell speaks in much the same way. After Foxworthy spoke at Liberty’s convocation -- promoting a Liberty global initiative, G5 Rwanda, under which students can sponsor needy children in the country -- the comedian and his family sat down to lunch with the Falwell family and some other key players at the university.

Sitting in the middle of a long wooden table, Falwell said he still has letters from a child he sponsored when he was in law school. He also said giving to the poor is conservatism in action. Liberals, on the other hand, want to vote for people who will have the government take and in turn give to the poor, according to Falwell. That, he believes, is so liberals can feel less guilty about not giving themselves.

Christianity, Falwell said a little later, is not about changing behavior. It’s about helping people. He also brought up Trump several times, describing a call he received from the president to thank him for his support on the cable news show Fox & Friends.

After lunch, Falwell returned to Marie F. Green Hall, a multipurpose former factory purchased for the university in the early 2000s by the conservative Green family, which owns the Hobby Lobby chain of craft stores. Today, the building holds administrative offices and the university’s law school, among other operations.

In the hallway, Falwell took a call on his cellphone’s speaker. After hanging up, he apologized. That was the White House counsel, Don McGahn, he said, without elaborating further.

Presidential Kingmaker

Some might be tempted to look back on the 2016 election and argue Liberty’s exploding growth was not enough for Falwell, that he felt the need to grasp for a bigger stage and play political kingmaker by endorsing Trump. But to do so misses the unique history of the university and the deep story of the man leading it.

The Falwell family and the university they founded have played a prominent role in American politics for the last four decades. At the height of the family’s political power, Jerry Falwell Sr. was a key player in swinging evangelical votes in 1980 from the Sunday-school-teaching Southern Baptist Jimmy Carter to the divorced and remarried Ronald Reagan. Liberty, meanwhile, has hosted countless conservative speakers over the years, as well as some prominent liberal speakers like Ted Kennedy.

That political dynamic didn’t change after the elder Falwell died and his son took over as Liberty’s leader. When Mitt Romney spoke at Liberty’s commencement in 2012, Falwell introduced the then presumptive Republican presidential nominee as “the next president of the United States.” Ted Cruz used Liberty as his backdrop when launching his presidential campaign. Even Bernie Sanders spoke at a convocation. And Trump appeared twice at the university before he was elected president.

Trump’s first appearance was in 2012, when Falwell called him “one of the greatest visionaries of our time” whose “business success in making his own dreams a reality is legendary.” Falwell said Trump started his business career in an office shared with his father before going on to list the world’s various Trump-branded properties, noting that Liberty would soon be replacing its oldest dorms.

“I think we need a Trump tower here on campus, don’t you?” Falwell said.

Falwell closed his introduction that day by calling Trump one of the most influential political leaders in the country. He gave Trump credit for single-handedly forcing President Obama to release his birth certificate, a reference to Trump’s long, discredited practice of questioning whether Obama was born in the United States.

Introducing Trump at his second Liberty appearance, in January 2016, when Trump was running for the Republican presidential nomination, Falwell called the candidate loyal to his friends. Falwell continued that introduction by referencing his own father’s stance years ago that electing a president was different from electing a Sunday school teacher, pastor or leader who shared his theological beliefs.

“After all, Jimmy Carter was a great Sunday school teacher, but look what happened to our nation with him in the presidency,” Falwell said. “Sorry.”

Falwell went on to draw parallels between his father and Trump.

“Like Mr. Trump, Dad would speak his mind; he would make statements that were politically incorrect,” Falwell said. “He even had a billboard at the entrance to this campus for years that read ‘Liberty University, politically incorrect since 1971.’”

Falwell said Liberty did not support or oppose political candidates -- a key point under tax law. As a 501(c)3 charitable organization, the university could not have supported a candidate without risking its tax-exempt status.

Liberty invited all other candidates from both parties to appear, Falwell said when introducing Trump. Less than two weeks later, he personally endorsed Donald Trump for president, sending a critical early signal to evangelical voters.

The move surprised some higher-ups at the university, who had expected Falwell to endorse Cruz. Recounting the endorsement recently, Falwell said he surprised himself, that he simply felt compelled to make sure Hillary Clinton was not elected president. But Falwell was all in on Trump from that point forward. He toured with Trump in Iowa before the state’s crucial caucuses. He recorded a robocall for Trump before the Super Tuesday primaries, accusing Cruz of “dirty tricks.”

Falwell would be rewarded that summer with a speaking slot at the Republican National Convention. That appearance marked the first time he’d ever been instructed by a speech coach.

There was a price to pay for endorsing Trump. Mark DeMoss, the chairman of Liberty’s Board of Trustees’ executive committee, left the board following a disagreement tied to Falwell’s support of Trump. DeMoss is a former aide to Jerry Falwell Sr. who has called the televangelist his second father, and he is the son of an important early Liberty donor, Arthur DeMoss. His family name still adorns Liberty’s main academic building.

DeMoss resigned in the spring of 2016, several weeks after telling The Washington Post that the Trump campaign was antithetical to the values for which Falwell Sr. and Liberty had stood.

“I’ve been concerned for Liberty University for a couple of months now, and I’ve held my tongue,” DeMoss said in the interview. “I think a lot of what we’ve seen from Donald Trump will prove to be difficult to explain by evangelicals who have backed him. Watching last weekend’s escapades about the KKK, I don’t see how an evangelical backer can feel good about that.”

The KKK reference was to Trump not disavowing an endorsement by former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke during an appearance on CNN. Trump had denounced Duke earlier.

DeMoss told The News & Advance of Lynchburg that he resigned from the executive committee after being told the committee had reached a consensus against his continued service on it. A few days later, he announced his resignation from the board.

Liberty has maintained that DeMoss could have stayed on the board after stepping down from its executive committee. But university leaders also said DeMoss violated his fiduciary duty as a board member by voicing concerns about Liberty’s future.

Since then, Falwell has proven to be perhaps Trump’s most loyal of backers, the surrogate who will defend the president when no one else will.

In the final run-up to Election Day last year, the Trump campaign found itself under siege after a 2005 videotape was released in which Trump described himself taking part in sexual assault. Trump, in the bombshell remarks, said he was “automatically attracted to” beautiful women and “I just start kissing” them. “When you’re a star, they let you do it,” Trump said in the recording. “Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.” Trump would issue a rare apology for the remarks and say he never acted on them, deeming them “locker room talk.”

Falwell told stood by the candidate, suggesting the GOP establishment had leaked the videotape as part of a conspiracy. Nothing was defensible about Trump’s remarks, Falwell said. But he also equivocated.

“We’re all sinners, every one of us. We’ve all done things we wish we hadn’t,” he told WABC Radio. “We’re never going to have a perfect candidate unless Jesus Christ is on the ballot.”

Falwell wasn’t the only one to continue to support Trump at the time. He wasn’t even the only evangelical leader, as Focus on the Family founder James Dobson continued to back the candidate.

Less than a year later, Falwell would find himself again defending the president amid a crisis. He was the one the Trump White House rolled out after the president delivered highly controversial remarks in the wake of a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., that turned violent. Falwell has longstanding ties to Charlottesville, having attended law school there at the University of Virginia. Charlottesville also is close to Lynchburg, about an hour and 15 minutes away by car.

Trump drew outrage when he said that there were “very fine people, on both sides” of the clashes. Neo-Nazis and white nationalists “should be condemned totally,” Trump said. But he also said that “you had a group on one side that was bad, and you had a group on the other side that was also very violent, and nobody wants to say that, but I’ll say it right now.”

One woman, Heather Heyer, was killed when a driver with reported Nazi sympathies allegedly drove a car into a group of protesters demonstrating against the assembled white nationalists. A man who has been identified as founder and imperial wizard of the Confederate White Knights of the KKK was charged with discharging a firearm within 1,000 feet of a school during the rally after a video showed a white man firing a gun toward a black man who had been using a spray can and lighter to shoot flames into the air.

In the wake of Trump’s Charlottesville comments, Falwell was grilled on Trump’s stance by Martha Raddatz on ABC’s This Week. He praised the president’s “bold and truthful” statements calling evil and terrorism “by its name,” and identifying Nazis, the KKK and white supremacists. Pressed whether he believed there were “very fine people” on both sides, Falwell said the president had information he did not have.

He went on to argue that Trump had made it clear that no moral equivalency exists between what counterprotesters had done, “even though maybe some of them resorted to violence in response,” and what one man had done by driving a car into a crowd “because he hates people of other races.” Raddatz asked if Trump could have been clearer.

“One of the reasons I supported him is because he doesn’t say what’s politically correct, he says what is in his heart, what he believes, and sometimes that gets him in trouble,” Falwell said. “But he does not have a racist bone in his body. I know him well. He is working so hard to help minorities and people in the inner cities.”

Falwell also told Raddatz that he had spoken with friends in the Jewish community in Charlottesville and a friend who is president at Hampton University, a historically black university. They helped him understand that they felt insecure and scared during the Charlottesville rallies.

Inside Higher Ed later asked who in the Charlottesville Jewish community Falwell had spoken with so that they could be interviewed for this article. Falwell responded that he actually gathered feedback through a public relations agency Liberty works with in New York. The PR agent talked to Jewish leaders and related the conversations to Falwell. That allowed Falwell to understand why people were offended and scared by the events in Charlottesville and Trump’s comments about those events, he said.

“I probably should have clarified that in my interview,” Falwell said, not breaking his normal speaking cadence.

Falwell has never met a white supremacist in central Virginia, he told Raddatz.

White nationalist groups operate near the university. The Southern Poverty Law Center lists one, the Wolves of Vinland, as being headquartered near Lynchburg.

Falwell’s defense of Trump after Charlottesville started a movement by Liberty alumni to mail their diplomas back to the university. He addressed that movement with Raddatz and in the friendlier territory of Fox & Friends and Fox News Radio’s Todd Starnes Show.

On the Todd Starnes Show, Falwell pulled no punches on the alumni movement.

“It’s a joke,” he said. “It’s so funny, because it’s grandstanding, is all it is. These people, there’s very few of them, but it happens at every college from time to time.”

If a graduate who mailed his diploma back needs his Liberty degree to apply for a job, he will put it on his résumé, Falwell predicted. That graduate can still use his degree after getting his “little five minutes of fame,” he said.

For those who mailed their diplomas back, however, the decision was no joke. Some said they have scrubbed all mention of Liberty from their résumés. Others could not locate their diplomas to return to the university but signed a letter objecting to its close alignment with Trump and Falwell’s support for the president. A total of 190 people signed a copy of that letter viewed by Inside Higher Ed.

Chris Gaumer graduated from Liberty in 2006 and is a former assistant professor of English at the university. He had two copies of his diploma that he returned to the university by mail. He heard no response, other than Falwell’s comments in the media.

“I know the alumni that I spoke with were just really blown away that the president, that his response was to attack the alumni, to diminish our numbers,” Gaumer said. “Liberty is an academic institution. A lot of the people who are in the group are thinkers or academics or people who at least have an observational interest in politics who understand this is a debate. To turn this into name-calling is to push the discussion into a quarrel. We are not interested in that.”

Bethany Hannah Walker, who started the Facebook group that originally urged alumni to mail their diplomas back to the university, was baffled by Falwell’s reaction to the diploma returners.

“What it says to the current student is, ‘Once we get your money and we cash you out and you move on with your life and you find in interviews that potential employers are, if not overtly hostile, then concerned about the kind of person you’re going to be, it’s damaging you, but we don’t really care,’” she said.

Walker graduated from Liberty in 2007 with a degree in English. Falwell’s support for Trump in the wake of his Charlottesville comments was the straw that broke the camel’s back, she said, but she had harbored concerns about the university and its leadership for years.

“He doesn’t respect us, because he’s in a really weird, unique situation of not really needing us,” she said. “They’re making a lot of money, or have been for years making a lot of money through the online program … I don’t think he cares about alumni. I think he cares about money.”

Other members of the diploma return movement put it differently. Becca Mancari is a singer and songwriter who graduated from Liberty in 2009. She didn’t get her diploma from her mother in time to mail it back to Liberty, but she did sign the letter protesting Falwell’s support of Trump. And she did not appreciate Falwell’s characterization of diploma returners as grandstanders.

“The names on this list are such good friends of mine still, who are so kind and so generous and so active in their communities,” Mancari said. “It’s obscene. That’s the word. It’s aggressive behavior by Jerry Falwell Jr. to say such things about such incredible humans.”

Falwell’s friends and acquaintances describe him differently. Kenneth Garren, the president of Lynchburg College, which is located near Liberty, said he and Falwell often consult on local issues. Falwell has always been helpful and supportive, Garren said, adding that Falwell will apologize when he realizes he’s made a mistake, but he won’t walk away from conflict.

“I’ll tell you, Jerry is a really nice guy,” said Garren, “but if you come after him in a fight, you’d better believe he’s going to fight you back.”

Another college president, Nido Qubein, who leads High Point University in North Carolina, said Falwell wants what’s best for his university.

“I don’t question the fiber of his belief or the fabric of his character,” Qubein said. “I think he just believes what he believes and talks about it authoritatively, and surely he’s aware that some people like what he says and some people don’t like what he says. He seems to plod forward regardless.”

Pennsylvania Avenue Perks

Many wonder whether Falwell’s support for Trump has paid off, if it has been worth the trouble. It’s too early to definitively answer that question, but Falwell argues the university has benefited.

“We got a whole lot of money -- donations -- Liberty did, from people who said, ‘We’re giving you this money because you supported Trump, you had the guts to do it,’” Falwell said. “It’s in the millions. I can’t remember the amounts, but enrollment’s bursting at the seams. I’ve gotten so many people that just -- our base loved it.”

Liberty’s contributions, gifts and grants were higher in 2016 than they were in 2015, according to federal tax filings. The university reported record on-campus enrollment of about 15,200 for the fall 2017 semester. Trump spoke at Liberty’s commencement this spring, visiting the university instead of taking the more traditional route of speaking at Notre Dame.

As for what Falwell personally has gained, the answer seems to be access to the White House.

Falwell has told reporters he declined an offer to be Trump’s secretary of education. At one point, Falwell had said he would be leading a presidential task force on higher education for Trump to address federal regulation of colleges and universities as well as accreditors. But no official task force materialized.

Nonetheless, in interviews and in meetings Inside Higher Ed was allowed to attend with Falwell, the Liberty president volunteered numerous pieces of information about his connections to the Trump White House. Trump sometimes calls to talk to Falwell, often after Liberty football games or media appearances, according to Falwell. And Liberty has also provided the White House with information on federal policy and regulations.

Robert Ritz, the university’s senior vice president of student financial services, gave a brief overview. Liberty provided information to the U.S. Department of Education on several key issues, he said: the borrower defense to repayment rule, gainful-employment regulations, third-party servicer fraud, and streamlining and simplification of the Title IV federal aid program -- particularly on the issue of duplicative reporting.

Many objections to those issues revolve around the idea that the Obama administration overreacted to a few extreme cases, laying on thick new layers of regulation and saddling innocent actors with high compliance costs. Many in higher education’s mainstream, particularly private colleges and their lobbyists in Washington, share that view with Falwell and Liberty.

“It’s the principle of applying regulations broadly to several thousand schools because there’s just a few bad actors,” Ritz said. “The assumption that you can’t go after a few bad actors under existing regulations, that’s the big picture.”

Falwell also brought up issues related to Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, the law that prohibits sex discrimination in federally funded education, and a hot topic after Education Secretary Betsy DeVos rescinded Obama-era guidelines and issued new guidance giving colleges more leeway in the ways they handle sexual assault cases. Like many universities, Liberty is currently tied up in its own Title IX legal fight. The university has been sued by three former football players who were dismissed from the university in September 2016 after they were accused of sexual assault at a 2015 off-campus party. The Lynchburg Police Department never filed charges in the case.

Law enforcement officers are the ones best qualified to protect victims, Falwell said. He believes colleges should be required to report allegations but investigations should be left to law enforcement.

This opinion differs from current law and the updated Education Department policy, which requires colleges to adopt procedures for resolving sexual misconduct claims. Trained investigators must investigate complaints and act on their findings. Administrators also must act when they should reasonably know of sexual misconduct incidents, the department says, no matter whether a complaint has been filed.

Liberty sent its feedback on the regulations to Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser.

“He was very impressed, thanked us for it, told us we were going to be involved,” Falwell said. “There’s been a lull in activity in the last two or three months. I think they’re busy on some of this.”

Liberty is not making policy decisions, Falwell said. It is not asking for favors. He views the college as simply telling the government what colleges must do to comply with what he sees as onerous regulations.

On the whole, the situation strikes some scholars as history possibly repeating itself. Jerry Falwell Sr. and other evangelical leaders are credited with helping to swing the presidency from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election. But some religious conservatives bemoaned the fact that they did not force Reagan to enact more policies they supported once he was elected.

“I’m wondering if this is the case with the son as well,” said Randall Balmer, a professor of religion at Dartmouth College and the author of several books on evangelicalism in America.

“Is there really anything he wants enacted?” Balmer said. “I don’t know what it would be. It seems to me he’s got everything he wants, having access to the president.”

Liberty Football’s Ascent

Liberty also made headlines on issues related to Title IX late last year when it hired Ian McCaw as its athletics director. McCaw resigned from the same post at Baylor University in May 2016, as claims piled up that Baylor’s athletics department mishandled reports that football players committed sexual assaults. Liberty said in November 2016 that McCaw “is a godly man of excellent character” and that if he made mistakes at Baylor, they appeared to be “technical and unintentional, out of line with an otherwise distinguished record.”

McCaw will play a key role as Liberty jumps to the top tier of college football. The move was made possible in February, when the university received a waiver from the National Collegiate Athletic Association allowing it to join the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision. The university needed the waiver because of a rule requiring schools to be invited by an FBS conference in order to make the jump. Liberty received no conference invite.

Liberty will start playing at the FBS level in the 2018 season. It plans to compete as an independent -- just like Notre Dame and Brigham Young.

The jump means more financial commitments for the university -- in the FBS, colleges and universities can award 85 scholarships, up from 63 at its current Football Championship Subdivision level. Liberty is also spending as much as $50 million to improve its football stadium and to expand seating from 19,200 to 25,000. A massive $29 million indoor football practice facility has already opened.

Falwell sees football as critically important to Liberty’s mission. The only real contact most people have with a university is through athletics, he reasons. Even alumni are most likely to return to campus to see a game. Athletics is not Liberty’s mission, but it highlights the university like little else can.

This is largely the reasoning Liberty leaders have been following for years as they pursued football -- the sport attracts attention and can be a vehicle for communicating about the university and about God.

The road to top-tier football has been long and difficult for Liberty. Falwell alleges some college presidents attempted to keep the university out of FBS by blocking its invite to a conference. He declined to name those presidents, however.

“Liberty was excluded just because two or three presidents out of 11 vetoed, because they didn’t want a faith-based school,” Falwell said. “They told that to people privately and it got back to us.”

The jump in football is not without risk. The Football Bowl Subdivision has been the center of dispute in recent years over whether players should be compensated and able to unionize. Its Power 5 conferences also decided in 2015 to offer full cost of attendance stipends to players, effectively allowing universities to pay cash to players to close the calculated gap between the scholarships they receive and the other expenses students face, like food and travel.

More generally, it is riskier today to invest in football than it has been in the past. The money is bigger in major college athletics, but health concerns about the sport have also grown. Worry about concussions and their effects on athletes continues to swirl around the game of football.

But McCaw argued medical safeguards have improved for student athletes. Football players are also benefiting from improved nutrition and stipends, he said.

“Student athletes have never had a better situation than they do right now,” McCaw said. “It’s never been a better time to be a college student athlete. The same thing for football.”

Falwell acknowledged rewards and risks.

“The TV revenues have really dropped for FBS teams,” he said. “We feel like there’s a lot of teams that are not going to be able to afford to stay in FBS, and once that happens, we think that’s going to open up opportunities for us. But there’s no way to predict that.”

Returns have already started, however. Liberty shocked Baylor to open the football season this year, upsetting an opponent from a Power 5 conference for the first time.

Risk and Reward

Like most leaders, Falwell has a complex relationship with risk. He’s clearly not afraid of the big gambles, like investing in football or backing Trump. But when previous risks pay off, he can be conservative with the proceeds.

Liberty has invested a low percentage of its endowment into equities, between 20 percent and 30 percent, according to Falwell. It’s taking risks instead by pouring profits into its campus.

Construction on Liberty’s campus isn’t just limited to its athletic facilities. The university is in the midst of a $1 billion campus construction plan funded in large part by its online profits.

Projects include academic buildings, dormitories and a 275-foot-tall tower topped by a replica of the Liberty Bell. The tower, which will hold the university’s School of Divinity, sits on an academic lawn that tour guides say is larger than the lawn at the University of Virginia. It is named the Freedom Tower. Some students have referred to it as the Tower of Babel.

Projects include academic buildings, dormitories and a 275-foot-tall tower topped by a replica of the Liberty Bell. The tower, which will hold the university’s School of Divinity, sits on an academic lawn that tour guides say is larger than the lawn at the University of Virginia. It is named the Freedom Tower. Some students have referred to it as the Tower of Babel.

Falwell believes in taking measured risks in areas where he can impact the outcome, according to John J. Regan, a partner and chief investment officer at the firm that manages Liberty’s endowment, Permanens Capital.

“We have a university president that sets the tone, which is, ‘We don’t need to take a lot of risk in this part of our operations,’” Regan said. “‘We’re taking risk in building the campus, and we’re taking risk in this online program, but we don’t need to take risk in this part of our lives.’”

Since Falwell took over, Liberty has also moved to formalize the way its board reviews investments. In less than 10 years, the university has gone from not having an investment committee or investment policy statement to having a committee that meets quarterly to review all of its investments.

Meanwhile, the university has been socking away money for the future. One goal is to have enough reserves that Liberty will be able to survive if online education becomes more and more competitive, eating into profit margins so that the online side of the university can no longer subsidize operations on campus. Another is to have enough money to operate a student loan program or provide guarantees to private lenders in case of major changes to the federal student loan program.

“We’re going to have to be so solid that if the online program completely went away, we don’t have to worry about money,” Falwell said.

Could Liberty license its online model to be used elsewhere? The university has not decided to do so, Falwell said. But he left the door open to such an arrangement. Liberty is already partnering with Hampton University. The universities aren’t disclosing the terms of that partnership, but plans call for it to involve athletics and online academics.

“I took my senior team up a few weeks ago to kick the tires, so to speak, because I heard a lot about their academic program, their online program,” said Hampton’s president, William R. Harvey.

Liberty is also more insulated from risk as an employer than are many universities, because its professors do not have tenure. Professors are on one-year contracts, with only a few exceptions -- the university’s law school does offer tenure protection, meeting an accreditation requirement from the American Bar Association.

Those contracts effectively shift risk to the employee. They make it easier for the university to fire professors who aren’t meeting expectations than it would be at a university offering tenure protection. They also could allow the university to shed employees quickly in the event of a financial crisis.

On the other hand, the lack of tenure means faculty members don’t have the same level of protection if they stake out controversial positions. And there are plenty of potentially controversial decisions at a conservative institution like Liberty. Employees are required to sign a doctrinal statement stating, among other things, that the Bible is inerrant and authoritative in all matters and that employees should uphold the “sanctity of permanent marriage between a man and a woman” and abstain from tobacco, alcoholic beverages and illegal drugs.

To Falwell, the lack of tenure does not constrain faculty members or the university. It attracts a certain type of professor.

“When you don’t have tenure, you’ve got people coming to work for you who know that nothing’s guaranteed,” he said. “It actually attracts people who are more risk takers to Liberty. And that’s what we want. We want risk takers. It’s one of the reasons we’ve been so successful.”

He also said the university has relaxed some of its requirements of students, like a hair code for men. Liberty used to ban hairstyles related to “counterculture,” restricting length and not allowing ponytails, but it dropped those rules. The university does not kick students out the first time they catch them taking drugs or drinking, Falwell said.

“We’ve never excluded gays,” he said. “Most people are surprised at that, but we never have.”

Yet murmurs persist that Liberty has a very different atmosphere when it comes to freedom of expression. Last year the university prevented its student newspaper from publishing a column criticizing Trump -- a move Falwell defended by saying the column was redundant with another piece. This week an evangelical pastor and author who has been critical of Falwell’s support for Trump said he was removed from campus and threatened with arrest after attending an on-campus concert Monday. Falwell said the removal was due to security concerns because the pastor had planned a protest and that Liberty’s tradition is not to allow uninvited protests.

Alumni who have been critical of Falwell say something isn’t quite right.

“People who work there now sent us horror stories of the type of fear that is instilled in many employees,” said Gaumer, the Liberty alumnus and former assistant professor who became a leading voice in the movement to return diplomas.

From department chairs all the way down the professional chain, the rule is to keep your head down and teach, Gaumer said. Those considering being publicly outspoken against the university know they are on one-year contracts.

“Traditionally, a university atmosphere is a haven for thoughtful discussion and curiosity,” Gaumer said via email. “At Liberty, I came to understand that voicing certain opinions makes you expendable.”

Falwell maintained that the university has only fired professors for a lack of competency. He could not recall an instance of firing anyone for making a statement the administration disagreed with or that was out of sync with the university’s mission.

Yet critics say conditions can limit free speech even if no one has been fired.

“I never got the sense that my professors were afraid to speak out openly for fear of losing their jobs,” said Walker, who started the Facebook group that urged alumni to mail their diplomas back to the university. “But Liberty University professors don’t have tenure, and you won’t catch them stepping out of line. It just does not happen.”

The university’s character has shifted since it started bringing in large profits, she said.

“I’ve known a lot of people who have been students and worked there,” she said. “They have lots of perspectives that I’ve heard, saying things changed in a big way once the school started making that kind of money.”

Others who have worked with Falwell say they trust him. Dennis Coleman, a lawyer with the Boston-based firm Ropes & Gray, represented Liberty as it worked to move up to FBS football.

“It wasn’t an engagement letter that consummated our deal, it was a handshake,” Coleman said. “[Falwell] is very comfortable in his own skin. I mean that in a good way. He’s at peace with himself because his belief is that he’s honest with people and he’s straightforward with people and that he’s doing things for the right reasons.”

Defining the Boundaries of Free Speech on Campus

Falwell’s views on free speech on Liberty’s campus are much more nuanced when he is questioned in depth. At a time when athletes’ protests during the national anthem -- and Trump’s comments about them -- have roiled football fans across the country, Falwell believes it is disrespectful to veterans to kneel during the anthem. Yet he would allow Liberty’s coaches to decide on a course of action if some players felt strongly about doing so.

He also thinks flying the Confederate flag is a bad idea for anyone.

“It symbolizes something that is just un-American,” Falwell said. “The white supremacist groups started using it as a symbol. I think the reason they started flying it was meant to be racist. I don’t think the groups, I don’t think they were flying it to say the South was fighting for states’ rights.”

Free speech issues are different for public colleges than they are for private colleges, Falwell said. That echoes established law surrounding the First Amendment, which says, as government entities, public institutions generally cannot block speech on their campuses. Private colleges, on the other hand, have more leeway.

Still, private institutions are making themselves look foolish when they support academic freedom but disinvite conservative speakers, Falwell said. So do students and protesters who turn to violence to keep conservative speakers off campus.

So should Harvard University have pulled its fellowship offer from Chelsea Manning after blowback?

Falwell deferred when asked that question, saying he was unfamiliar with Manning, who spent years in military prison for leaking classified documents. Told who Manning is, Falwell did not answer directly.

“I don’t really understand the question, because it’s not a conservative or a liberal thing,” he said.

Should Milo Yiannopoulos, the conservative speaker and focal point of many recent free speech disputes, be allowed to speak on campuses despite a track record of inflammatory statements? Falwell again said he did not know the speaker. But after Yiannopoulos’s background was briefly explained, Falwell offered some thoughts on the boundaries of free speech.

“It’s just like yelling ‘fire’ in a crowded theater,” he said. “If somebody is coming in to say things that are provocative, going to cause violence, then I think that’s where free speech ends. That’s what -- liberals used to say that forever. They used to say, ‘I might disagree with what you’ll say, but I’ll die for the right to say it, but you can’t yell “fire” in some crowded theater.’”

Would Liberty host a speech by Bill Maher, the liberal talk show host? Yes, Falwell said. The university would also consider hosting Kathy Griffin, the comedian who drew outrage earlier this year for posing in a photo shoot holding a mock-up of a severed Trump head -- if Griffin had “something of value to say.”

Asked whether Liberty would host Colin Kaepernick, the professional football quarterback who sparked the protest movement by kneeling during the national anthem last year and who has since filed a grievance after he was unable to find work in the National Football League, Falwell said he did not know who the athlete is. After Kaepernick’s history was explained, Falwell said the quarterback would be allowed to speak at Liberty, but that he doubted any student group or department would invite him.

Fielding All Questions

What Falwell has not done is shy away from questions about his politics or his leadership after he supported Trump. Many faculty members and college presidents are in the public eye, taking political positions, he said. He just happens to be one of the few on the conservative side.

Falwell does not, however, see himself as a model for a newly politically active university president. Many presidents still rise through academic ranks, and he does not believe academics go into their fields to be political warriors. They are risk averse, seeking tenure and long-term job security.

He also admits that his outspoken support of Trump could have turned away some students.

“For every one that didn’t come here, I think there’s probably two that did,” he said. “So many schools are in lockstep politically that if you just happen to be on the other side, you’re such an exception. That’s one of the reasons Liberty is a big draw -- it’s kind of like the Fox News of academia.”

Falwell’s personality is enmeshed with Liberty’s trajectory more closely than many other college presidents’, because the university is in many ways run like a family business. Falwell remembers being 8 years old when the institution’s founding was announced. His whole life is engrained with the purpose and mission of Liberty, he said.

He described himself as a fighter, someone who feels derelict in his responsibilities if he isn’t struggling for something. Sometimes he grows bored. At those times, he stirs the pot, sending out a controversial tweet just because things have grown too quiet.

That self-identity as a fighter incorporates Falwell’s feelings about Lynchburg, his family history and even, to a certain extent, religion.

Falwell knows his family history -- he spent three years researching it for his father’s 1987 autobiography, Strength for the Journey. His grandfather owned numerous businesses, including a nightclub, bus lines and an oil company, using some of those businesses to distribute moonshine. But according to the biography, his grandfather died of cirrhosis after years of drinking fueled by guilt brought on by a dispute in which he shot his brother dead. He was acquitted of murder on the grounds of self-defense.

“My mom, when she started dating my dad -- who was only 15 when his dad died -- her parents were mortified because they were middle-class, churchgoing people, and the Falwells were just -- I mean, they were just rough businesspeople, and my dad’s granddad was an atheist,” Falwell said. “I take more after dad’s side of the family. It’s just a fact. I do.”

Lynchburg, Falwell said, has always had a wealthy group of blue bloods. He believes Liberty had to fight them every step of the way. In the 1980s Liberty threatened to move to Atlanta because local politicians charged real estate taxes on its campus despite its nonprofit status. The university bought the nearby New London airport at the end of 2015 for a reported $1.8 million to support its School of Aeronautics, a move that came just a few years after the Lynchburg Regional Airport director pushed back against a Liberty-owned plane service’s expansion, arguing it was creating a monopoly on aviation services at that airport.

“I basically ended up buying another airport, a dinky little airport,” Falwell said. “The zoning is there if I want to lengthen the runway. I can, just to let them know that they weren’t going to control us, that they were going to give us a good deal and they were going to run it right -- or we’re going to be able to compete with you and you’re going to be out of business.”

Does Falwell ever worry about the people who get caught in the cross fire in his fights?

“My family, you mean?” he asked.

Yes. Or anyone else.

Falwell pointed at his son, Jerry Falwell III, whom the family calls Trey. Trey Falwell is Liberty’s vice president of university operations.

“He gets caught in the cross fire sometimes,” Falwell said. It was a reference to recent press coverage of Trey Falwell’s real estate investments in Miami and a house he bought from Liberty that was not listed as a line item on the university’s federal tax forms. The home sale appeared to fall under IRS reporting requirements for business transactions with an interested person. Liberty has said the home sale was properly disclosed. Falwell said his son is investing in a distressed property in Miami, just as he himself has done as a developer.

Debating University and Religion

The people Jesus criticized most, Falwell said, were the people who thought they were better than everybody else. That view came through in Falwell’s argument for Trump after the Access Hollywood tape was released.

“All I said was everybody’s sinned,” Falwell said. “If you believe your Bible, read it. That’s what it says. One person’s not better than the other one because they did this and this and this guy doesn’t.”

This reasoning angered even some of Liberty’s current students. Dustin Wahl is a student who started the Liberty United Against Trump movement during the presidential election. The group has criticized both Trump and Falwell’s support of the candidate. Wahl, a 22-year-old political science major who will graduate this spring, believes Liberty is an institution that is greater than its founding family and president.

“I think he thinks Liberty is his,” Wahl said. “And he is right about that, to a degree. But I think he thinks that it’s just totally his, and I think it’s the students’. And Mark DeMoss thought that it was the administration’s and the students’ and the whole of Liberty’s, and that view has been hostile and foreign to President Falwell.”

In many ways, the disagreements over Falwell’s leadership and Liberty’s direction reflect the divisions running through conservative Christianity and evangelicalism in America.

“We can debate what Liberty University is,” Wahl said. “Falwell thinks it’s his, and I think it’s the students’. If it is the students’, then Liberty is more about Christianity. If it’s Falwell’s, maybe it’s more about politics.”

Rebekah Tilley (no relation to Becki Falwell) graduated from the university in 2002, majoring in government. She says she couldn’t get a job she wanted with her Liberty degree and went on to earn her master’s from the University of Kentucky.

“Frankly, I came out under his father’s tenure, and I feel like, compared to what this generation is going to have to face, how politicized Liberty has become under Falwell Jr., it’s going to be worse,” she said.

Tilley was one of the Liberty alumni in the movement to return diplomas. Her diploma was destroyed in a flooded basement, but she gathered her honors thesis, a program from her graduation ceremony, awards she received as a senior and every last remnant she could find from her time as a student. She mailed the documents to the university in an envelope with a letter explaining why she was returning them. She received no response.

She felt she had to say something if she cared about the institution, Tilley said. When Falwell did interviews diminishing the move to return diplomas, she questioned his leadership.

Tilley doesn’t doubt that Falwell considers himself to be a faithful Christian. While that does not mean he is a Christian leader, many across the country assume he fills that religious role because his father was such a high-profile preacher.

“I wish he recognized that more people kind of see him in that vein,” Tilley said. “Because maybe then he would understand how deeply he is wounding evangelical Christianity right now because of his actions.”

Scrolling through Falwell’s Twitter feed reveals very few biblical or religious references. The Liberty president is comfortable with that, although his reasoning might surprise some.

“I think there’s a difference between religion and Christianity,” he said. “I think Christianity is how you treat other people. Religion is all the other stuff -- you know, going to church, quoting Scripture all the time. I think a lot of people worship the Bible instead of worshipping Christ.”

Falwell gives Liberty’s spiritual leadership space to operate. When David Nasser, the university’s senior vice president for spiritual development, interviewed for his job several years ago, Falwell told him he could run his own team and strategy. Falwell has not micromanaged in the years since then, Nasser said.

This does not mean that Falwell never references the Bible in conversation. He brought up the parable of the talents, the tale of a master leaving property with servants and then evaluating how they had invested it.

We are supposed to love others as we love ourselves; we are supposed to love God, Falwell said. We also are supposed to do the best we can with our own skills, he said, rendering unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and rendering unto God the things that are God’s.

“When you’re serving a corporation, you do what’s in the best interest of the corporation,” he said. “When Jesus said turn the other cheek, he wasn’t talking about -- he didn’t mean for a soldier in battle to turn the other cheek.”

It can be argued that Falwell is in a suddenly uncomfortable position of strength. He has gone from the daily triage of keeping Liberty alive to the responsibilities of shepherding a thriving university made up of thousands of students, faculty, alumni and trustees, all with their own needs and opinions. He has gone from stumping for Trump, a Washington outsider, to defending a president in power.

In some ways, that arc runs parallel to the story of the evangelical movement itself.

“These people are very, very skilled at the rhetoric of victimization,” said Balmer, the Dartmouth professor. “So is Trump, by the way. And I think that’s one of the reasons Trump won the evangelical vote. This rhetoric of victimization is very potent.

“Any time you turn that around, they’re drifting somewhat.”

So where does Falwell go from here? When does he declare victory and walk away?

Falwell has thought about that question. Because of the stresses of his early years guiding Liberty through its financial troubles, he describes his time at the university as being 50 years squeezed into 30. In the last few years, he has started delegating more responsibilities to other administrators than in the past.

He’s not ready.

“I could see myself saying, OK, just 15 more years, I’ll be 70 and maybe just enjoy the rest of it,” Falwell said. “I don’t know if I could handle not being in the middle of the fight.”