You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

College students began arriving in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., in early March for annual spring festivities amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Observers seeing recent reports of crowds of maskless young people, many presumed to be college students, partying on Florida beaches for spring break may have had flashbacks to March 2020, when the scenes were much the same, just weeks after the coronavirus pandemic had been declared and colleges were hastily throwing together plans to keep potentially infected students away from campus.

Students at the time were either unaware of the risks that the virus posed or blatantly disregarding those risks, as they reveled in Miami and Daytona Beach. Some people may have been surprised to see the same behaviors being repeated this year, albeit with greater public knowledge about the virus and as the new vaccines are being administered to people across the country. Experts tracking student behavior during the pandemic were not at all surprised, however.

Laurence Steinberg, a professor of psychology at Temple University and a leading expert on adolescent behavior, said that students are getting mixed signals right now about whether it’s safe to do away with some of the precautions that the public has been urged to follow during the pandemic. He noted recent declarations by Greg Abbott of Texas and other governors that their states are “100 percent open” and the lifting of mask mandates.

“College students are no more immune to those messages than everybody else is,” Steinberg said. “Because of their age, they may be more susceptible to believing the good news, which the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] says is an incorrect message. In terms of what colleges can do, there’s not a great deal.”

But colleges this year at least had several months to prepare and protect their campuses. Many decided ahead of time to eliminate spring break and, with it, the potential that students would return to campuses with a COVID-19 infection that could then spread into neighboring communities.

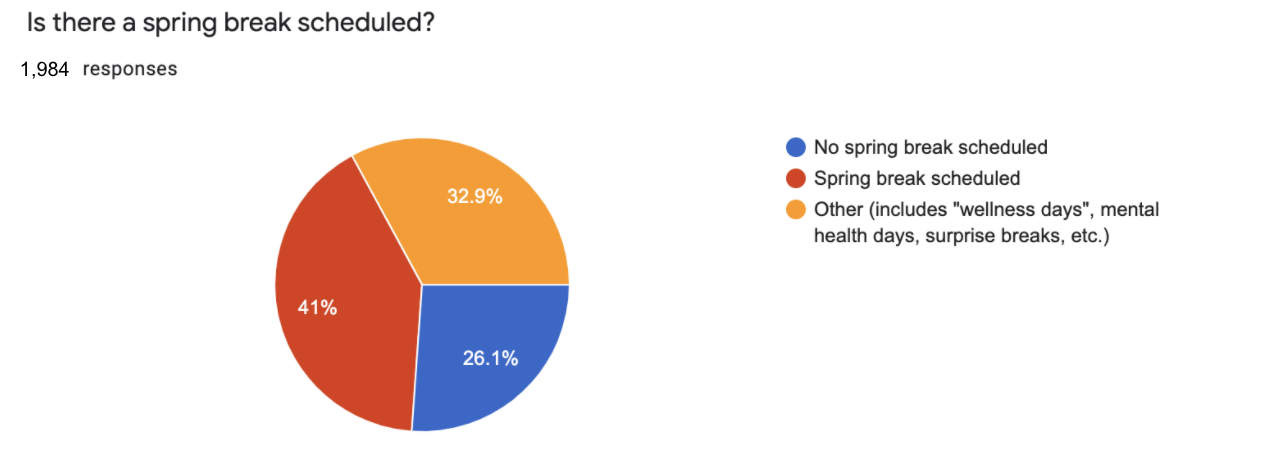

According to researchers tracking colleges’ pandemic response plans, the reality for a majority of students this year is no traditional week off for spring break. Nearly 60 percent of colleges either canceled spring break outright or are offering students sporadic “wellness days” off during the semester instead, while also discouraging travel away from campus, said Chris Marsicano, a higher education professor of practice at Davidson College and founding director of the College Crisis Initiative, or C2i.

The initiative, which tracks institutions’ responses to the pandemic, reviewed the spring break plans of nearly 2,000 colleges and universities, some of which had already announced cancellations of spring break during the fall 2020 semester. The colleges' wellness days ranged from scheduling long weekends in the academic calendar (about 23 percent) to canceling classes on one or more days in the middle of the week (about 46 percent), Marsicano said in an email.

The initiative, which tracks institutions’ responses to the pandemic, reviewed the spring break plans of nearly 2,000 colleges and universities, some of which had already announced cancellations of spring break during the fall 2020 semester. The colleges' wellness days ranged from scheduling long weekends in the academic calendar (about 23 percent) to canceling classes on one or more days in the middle of the week (about 46 percent), Marsicano said in an email.

Anne Ridenhour, a senior at Davidson and a co-chief of operations for C2i, said the spring break cancellations reflect a recognition by colleges that student movement can increase case counts on campuses and in the communities that surround them. One study published online in May 2020 and soon to be published as an article in the Journal of Urban Economics used cellphone data and academic calendar information to suggest that spring break travel to Florida and New York City last year increased COVID-19 spread upon students’ return to campuses.

The calendar changes by colleges made it less likely that students would be jet-setting to popular spring break destinations this year, said Paul Niekamp, a professor of economics at Ball State University in Indiana and co-author of the student travel study. He suggested that some students may have immunity to the virus if they previously recovered from it, and that some vulnerable people have been vaccinated, both of which were largely not the case last year. Still, it “isn’t a good idea for college students to travel for spring break,” Niekamp wrote in an email.

“There is still the risk students can bring infections back to campus and cause outbreaks,” he said. “That being said, policing behavior of college students can be difficult, so it is still a good idea to follow university and CDC policies on testing and quarantine upon return to campus.”

Rochelle Walensky, director of the CDC, pleaded with Americans on Monday to avoid travel and remain vigilant about pandemic safety precautions. She noted in a White House briefing that more than 1.3 million people traveled on airplanes on March 12, the most travelers that the country has seen in a single day since the pandemic was declared last year.

“I know it’s tempting to want to relax and to let our guard down, particularly after a hard winter that sadly saw the highest level of cases and deaths during the pandemic so far,” Walensky said. “We have seen footage of people enjoying spring break festivities maskless. This is all in the context of still 50,000 cases per day.”

Ridenhour said that colleges have had to weigh the ethical choice of canceling breaks to prevent virus spread against the demands and desires of students to have some sort of break from classes at a time when they're already stressed by the demands of attending college during the pandemic, feeling disconnected from their friends and altering their social lives and expectations about the college experience. Survey after survey of students show that their mental health is suffering as a result of the increased isolation, loneliness, loss of normality and grief over the death or illness of family members.

“You have to balance trusting your students and giving us the break that I would argue we deserve,” Ridenhour said.

Kelly Davis, associate vice president of peer and youth advocacy for Mental Health America, said anniversaries of traumatic events, such as when campuses were shut down around this time last year due to the pandemic, can be especially stressful for students.

“They're probably dealing with that at the same time, thinking about, ‘When will this really end? When will things be a new normal?’ There’s a lot of other things causing stress for students, and the absence of a break is a continuation of an environment that is leaving a lot of young people anxious, burned out and stressed,” Davis said.

Some colleges that did not cancel spring break have invested in strategies to encourage students to remain local during the time off. The University of California, Davis, on Tuesday gave about 2,500 students who are staying in town for spring break $75 gift cards to local businesses. Sheri Atkinson, vice chancellor for student life, campus community and retention services, said the gift cards offer students opportunities to take part in local activities. For example, there are gift cards for a local running and exercise store and for a bookstore, Atkinson said.

To be eligible for the gift cards, students have to be living in Davis during the break -- about half of the nearly 40,000 students enrolled do, even though classes are mostly online, Atkinson said. Students participating in the incentive program must also get a COVID-19 test from the university during spring break, from March 20 to 24, which will provide some proof that they’ve stuck around during the week, she said.

“Our students here at UC Davis have been doing a really good job for the most part, so we wanted to do something positive for them to stay here and continue that positive behavior,” Atkinson said.

Students at other colleges and universities around the country have generally taken note of and appreciate the efforts by administrators to provide a couple of days off from classes, in the absence of a full week for spring break.

However, some students have found the wellness days to be better in theory than in practice, Davis said. Students don’t actually get a break unless professors are explicit about not scheduling assignments around the wellness days and unless the students can also take off from work, childcare duties or other responsibilities not related to their academic work.

“For me, these wellness days so far haven’t really been wellness days,” said Helmi Henkin, a graduate student in the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis, which is giving students four days off in lieu of spring break. “Even if I don’t have class, I have two part-time jobs, and as part of my program I have to do an internship.”

“Having these one-off days isn’t very restful and in addition, professors have varying levels of understanding,” Henkin said. “You might have the day off, but that doesn’t mean professors won’t assign ginormous exams that week.”

Brayden Soper, president of the Associated Student Government at Emporia State University in Kansas, said traditional spring break can “be a huge relief” for students who want to travel safely to see family members or take time off work. Emporia State students, who will get two wellness days this semester, are some the luckier students in the Kansas state university system. Most of the system’s six institutions canceled spring break and three won’t be providing any wellness days, Soper said.

The two wellness days at Emporia State also allowed the university to shorten its spring semester, but Soper said students are less likely to notice that change. They’re most in need of a break midsemester, when midterms are finished and mental health is poor, he said. If hanging out with friends after class or grabbing a drink or a bite at a restaurant are no longer safe options, opportunities to blow off steam or decompress are lost, he said.

“We haven’t been reminding ourselves enough of how important mental health is,” Soper said. “Part of that is because of how strict the rules have to be due to the pandemic … It’s important to remind students to take that time.”