You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Yan Krukov/Pexels.com

The National Institutes of Health says that 75 principal investigators have been removed from grants due to sexual harassment and other hostile workplace claims in the last three years.

Separately, the National Academy of Sciences says that it has removed two members due to sexual misconduct.

Prior to 2018, no PI had been removed from an NIH grant for sexual misconduct. The National Academy hadn’t removed any members for this reason, either, prior to this year.

The Me Too movement and specific campaigns against sexual harassment and assault in the sciences pushed these organizations to consider behavioral misconduct as seriously as research misconduct. But it took years in some cases for these consequences to play out.

Removing Prestige

The NAS removed astronomer Geoff Marcy, for instance, late last month, for violating Section IV of its Code of Conduct, which prohibits “all forms of discrimination, harassment and bullying” in professional encounters, “especially when they involve power differentials, as these behaviors have adverse impacts on the careers of scientists and the proper conduct of science.” The decision followed an internal conduct review process.

The NAS council approved its Code of Conduct in late 2018. Marcy resigned from the University of California, Berkeley, in 2015, amid public pressure, after a university investigation found that he’d repeatedly violated its sexual harassment policies. The allegations against him involved unwanted groping, kissing and massages of students over a decade. Marcy has said he doesn’t agree with all the findings against him but that it’s "clear that my behavior was unwelcomed by some women."

The NAS removed biologist Francisco Ayala, who resigned from the University of California, Irvine, in 2018, just last week. A university investigation found multiple sexual harassment claims against him to be credible. His accusers, including some fellow professors, included unwanted touching and rubbing. One accuser said Ayala had commented that she was so enthusiastic during a presentation that he thought she would have “an orgasm.” Ayala has said he regrets that “what I have always thought of as the good manners of a European gentleman” made his colleagues “uncomfortable.”

Several survivors of sexual misconduct in the sciences said last week that they welcome these actions by the NAS and NIH. At the same time they emphasized the costs of the reporting process -- beyond the actual harassment they experienced -- in time, energy and emotion.

“What’s really clear at this point is that it takes overwhelming evidence and many victims coming forward to get any of these other organizations to act,” said Kathleen Treseder, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Irvine and one of Ayala's accusers. “Things are so entrenched that it just takes a mountain to move these people.”

Treseder added, “I would love to have that bar lowered to where we expect a very basic level of professional decorum. I don't think we're anywhere near that point. But this is good start.”

Jade Guedes, associate professor of geosciences at the University of California, San Diego, agreed that university investigations -- on which the NIH and NAS remain reliant for their own deliberations -- are too onerous for victims. Guedes reported anthropologist Gary Urton, whom Harvard University recently stripped of his professor emeritus status and banned from campus, for emailing to invite her to a hotel room for “conversation and exploration.”

Guedes was a graduate student at Harvard at the time of the email. While the proposal was bad enough, it pales in comparison to other complaints against Urton that Harvard received, she said. Yet other victims were taken less seriously because they didn’t have a “smoking gun” in the form of an email.

“The harassment has to be so bad and so pervasive at such an extraordinary level before they fire someone that to me, what that basically says is that there are many other harassers who are just not at that level,” Guedes said.

Urton retired in 2020, during the university’s investigation based on Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits gender-based discrimination at federally funded institutions. He's said that for "many reasons, I do not feel the sanctions against me are fair or just, nor do I believe they accurately reflect the evidence gathered during the Title IX proceeding.”

Following the Money

In 2018, Francis Collins, director of the NIH, publicly denounced sexual harassment as “morally indefensible” and “unacceptable.” He also announced the launch of an anti-sexual harassment website and previewed forthcoming initiatives, including a centralized process for managing reports of harassment.

The federal funding agency eventually launched a web portal through which concerned parties may file complaints about funded scientists directly with the NIH. The agency is currently creating a hotline for such complaints, as well.

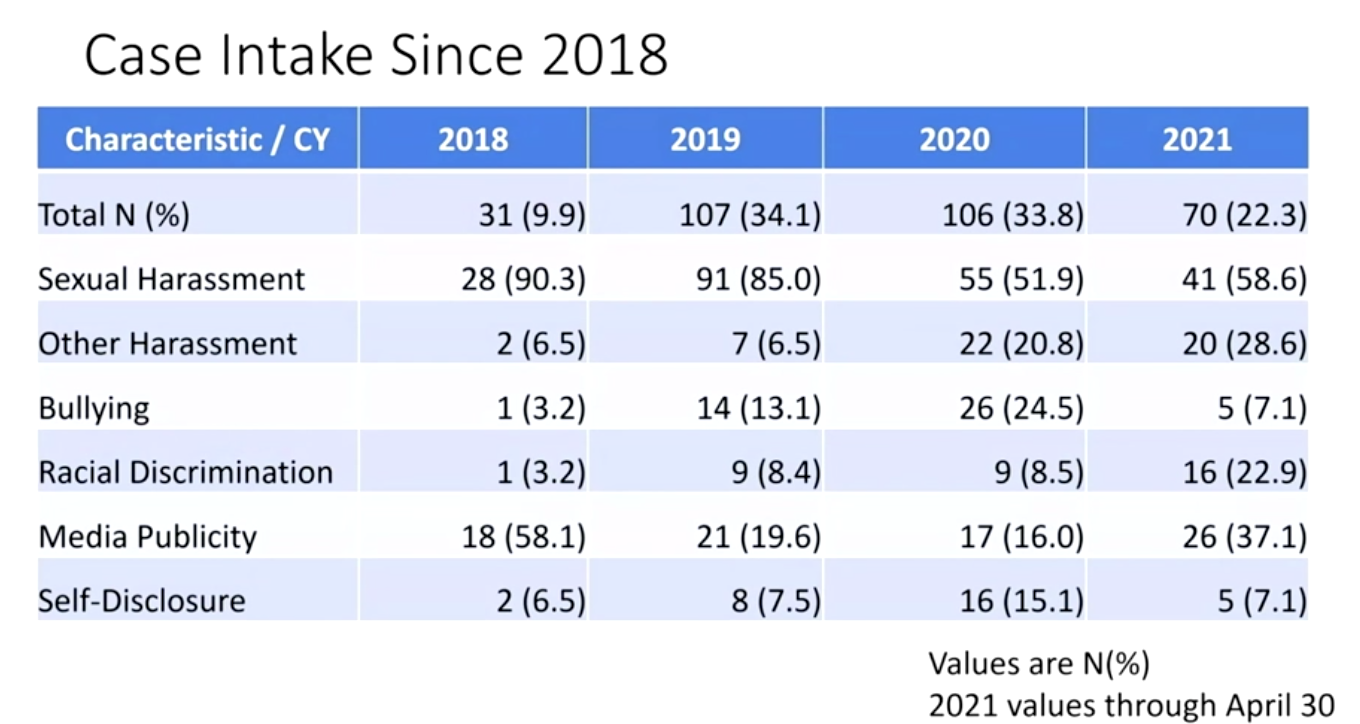

In a meeting this month of the NIH’s Advisory Committee to the Director, the agency revealed that it has received reports of behavioral misconduct against 314 grantees total since 2018.

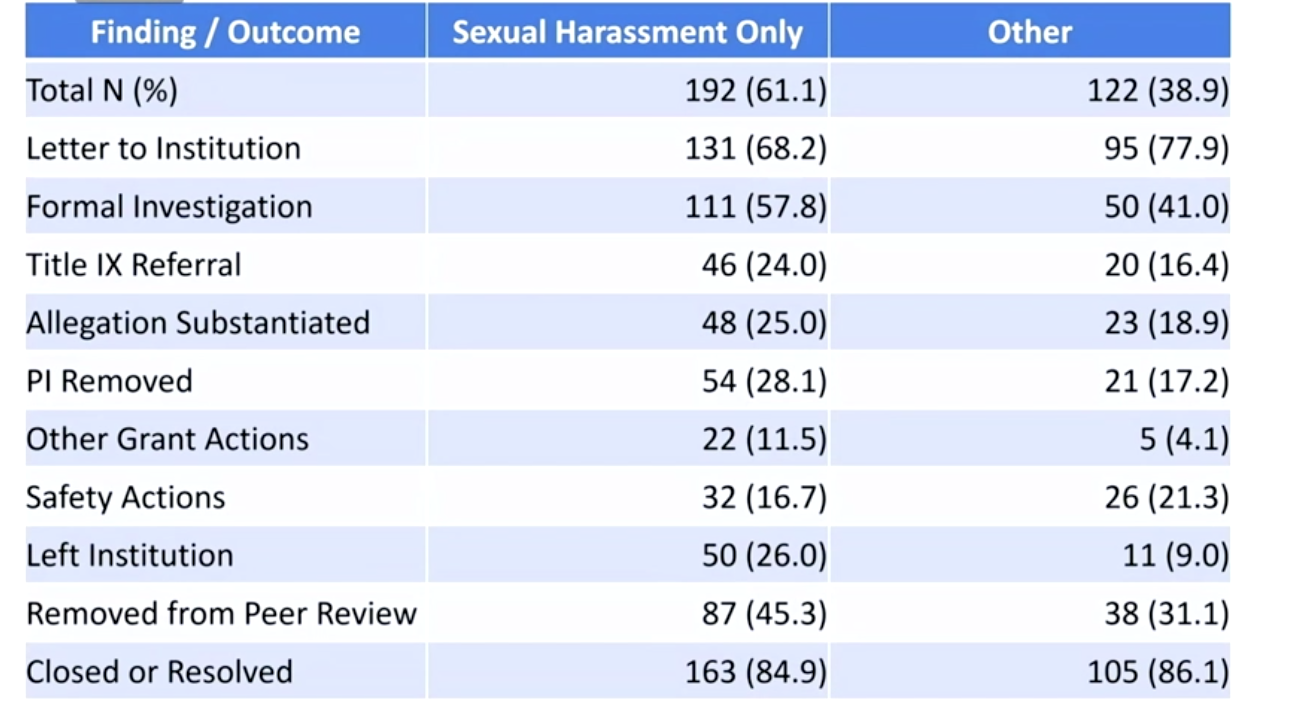

Some 163 of cases resolved since that time involve sexual harassment. Regarding these kinds of cases, the NIH sent letters of inquiry to 131 institutions upon hearing of a complaint. In 48 of 163 resolved cases, the institution substantiated the allegation or allegations through its own processes. In 54 of these 163 cases, the PI was removed from the NIH grant. In 50 of these cases, the PI left the institution before they could be removed from a grant.

The scientist was removed from the peer review process for grants in 87 cases.

Seventy complaints of the 314 total were filed between January and April 30 of this year alone. Forty-one of 70 involve sexual harassment. Sixteen involve racial discrimination, and complaints of this nature have increased in number each year since 2018. Five of the 2021 complaints involve bullying. Some complaints involve other types of harassment, or multiple types of harassment.

Mike Lauer, deputy director of the NIH Office of Extramural Research, said during the meeting that he’s “sending out three to four letters a week” to institutions, trying to resolve complaints.

While the pandemic may have upended some lab work, he said, there’s research to suggest that “some of our social skills have atrophied that may lead to more conflict and hostility in the workplace if that’s not carefully managed.”

The National Science Foundation in 2018 began requiring that funded institutions report harassment findings against principal or co-principal investigators, as well as when PIs are put on administrative leave. Possible consequences include removing the PIs from grants, but the NSF said last week that it doesn’t track these removals similarly to the NIH.

Science reported that the American Association for the Advancement of Science ejected two fellows, including Ayala, last year over harassment findings. This resulted from a 2018 policy change allowing for such action.

The NIH has required institutions to report when a PI is removed from a grant due to harassment findings since last year.

How does the NIH complaint system work? The NIH does not remove grantees from awards on its own but works with institutions in a number of ways to achieve that goal.

Lauer described three examples of processes. In the first, he said, an institution’s vice president for research contacts the NIH directly to say that a PI violated that university’s sexual misconduct policy, and that a rapid investigation was conducted. The university sanctions the offender and proposes a “management plan” to the NIH, which involves removing the scientist from NIH grant activities. There’s some back-and-forth between the university and the NIH, Lauer said, during which the investigator is replaced and even removed from peer review.

“This is a situation where things go relatively smoothly,” Lauer said.

In another scenario, Lauer said, “we get an anonymous complaint through our web form that will provide us with a link to a report of sexual misconduct, somebody that we didn’t know anything about. And we then contact the institution. And we ask the institution what's going on.”

The institution responds, saying it’s sanctioned the PI, such as by not allowing the scientist to supervise students alone or be in contact with certain people, Lauer continued, “but there are no problems with the NIH grants -- they can continue to serve as PI on NIH grants. And so then I come back and say, ‘We don't quite understand. Somebody who cannot be trusted to supervise certain individuals or be an adviser for graduate students who are in a highly vulnerable state, how are we supposed to believe that the research is being conducted in a safe environment and that this person can be trusted?’”

This leads to some “rather difficult conversations,” Lauer said. “And we have now had quite a number of cases where the university has said, ‘You know, you’re right, we understand where you’re coming from here. And so we are going to remove this PI from NIH grants and we’re going to get another PI to take over that lab or take over the situation.’”

In a third example, which Lauer said is the most difficult of all, the NIH receives an anonymous report about a particular PI who resigns from a campus amid a Title IX investigation.

“In some cases, there's a nondisclosure agreement” between the PI and the university, Lauer said. “So the understanding is, they leave the institution, the institution will not tell anybody what's going on, they get a job [someplace else].”

Because the PI has now left the institution, the investigation stops and there is no formal finding, Lauer said. "Many, many times the scientists are seemingly superstars. They get an offer from another institution that is oblivious and does not know what's going on -- they may think that they have succeeded in [attracting] an incredible recruit."

The first institution submits a relinquishing statement to the NIH giving up the PI’s grant, and the new institution files a form seeking to pick up the grant, Lauer said -- but the NIH's hands are tied. “We know that there's a really serious problem, that that lab has been the site of some very serious violations, and there's nothing that that we can, seemingly nothing that we can do. And it gets us into a really difficult spot.”

Given the seeming loophole in this last scenario, and the potential conflicts of interest that university Title IX investigations entail, Treseder and Guedes both said that external bodies such as the NIH and NAS should begin conducting their own parallel investigations into misconduct complaints.

Guedes, in particular, noted that independent hostile workplace investigations have been a pillar of some recent graduate student union organizing efforts.

“That would certainly help the process,” Guedes said of investigations by professional societies. These bodies assume certain responsibilities when they elevate a scientist's status and therefore power by virtue of funding, prestige or both, she added.

“Part of what is so difficult about the university conducting an internal investigation is that it is biased, right?” Guedes continued. “It is protecting university interests first and foremost. And it has professional consequences for the accuser or survivor at that university. There are all kinds of threats or intimidation that could happen there that could make it very difficult for the person who was accusing someone to actually want to move forward.”