You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

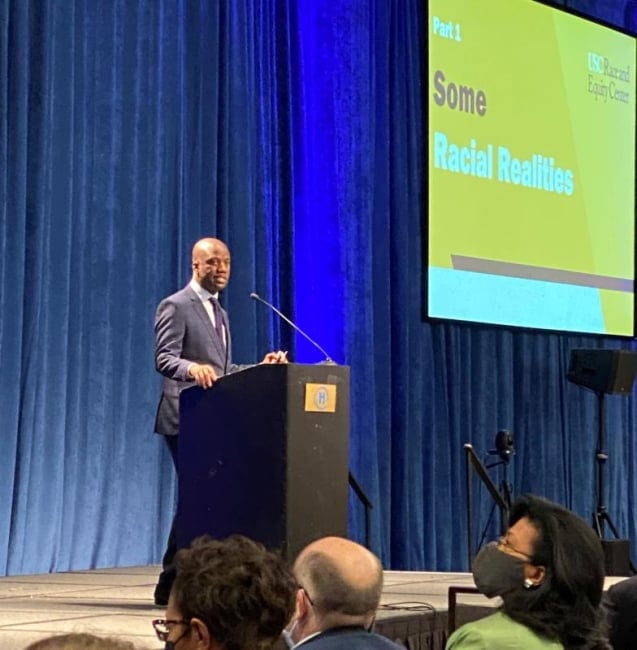

Shaun Harper speaks to the State Higher Education Executive Officers.

SHEEO

WASHINGTON—When state higher education leaders gathered (in person!) here last week, their agenda included the usual topics: expanding access to college, improving completion and ensuring that students are prepared for work and life after graduating. But their first major gathering since before the COVID-19 pandemic was also their first convening since the other major world-shaking event of 2020: the racial justice upheaval in the wake of multiple killings of Black Americans by police.

The extent to which that set of developments has reshaped the priorities of many higher education leaders was evident in the prevalence of topics related to equity and diversity on the agenda of the State Higher Education Executive Officers’ Higher Education Policy Conference. Almost half of the 50 or so individual sessions touched meaningfully on those themes, a noticeable increase from previous years.

The group’s leaders also ensured equity wouldn’t get lost in the shuffle by opening the meeting with back-to-back speakers who put the issue of race in sharp relief. Adam Harris, the Atlantic writer and author of The State Must Provide: Why America’s Colleges Have Always Been Unequal -- and How to Set Them Right (Ecco), spoke at the opening dinner about how public policy on higher education has historically prioritized the interests of white students and the need to address that now.

For the first morning’s keynote address, SHEEO turned to someone who has made a habit of calling out how various parts of the higher education ecosystem have themselves contributed to inequitable opportunity: Shaun Harper, founder and executive director of the University of Southern California’s Race and Equity Center.

Pre-pandemic, Harper shook up gatherings of admissions officers and scholars of higher education (his home turf) by calling out racist practices that he believed worsened rather than enhanced equity in higher education. That was before the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor made “Black Lives Matter” a household phrase and forced colleges and universities to look in the mirror at their own complicity—even if their campus hadn’t experienced a racial incident, the usual prompt for such self-reflection.

The events of 2020 and the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on minority and low-income students, already underrepresented in higher education, only intensify the need for college leaders to take equity seriously, Harper told the scores of state higher education policy makers relishing being back together at the SHEEO conference last week.

Harper spent the first part of his presentation—“Racial Equity Through Raceless Policy Making?”—discussing the “litany” of signs of racial, socioeconomic and other inequities in higher education. Gaps in educational outcomes between Black, Hispanic and Indigenous students are large and expanding because of the pandemic. Campus climate surveys conducted by Harper’s center at USC consistently reveal discrimination faced by minority students.

Even employees at 71 private colleges that work with the USC center overwhelmingly concede that their institutions have “serious racial problems,” Harper said. “It would surprise me if the staff had a different appraisal of the seriousness of racial problems at the public campuses you oversee,” he told the state higher ed leaders.

Evidence of racial issues alone does not ensure that the issues get discussed, Harper said. “Avoidance is the primary way we deal with issues of race” in many workplaces and other settings, he said, and it is often left to employees of color to raise the issues.

“It’s as if we were born with some superpower that enables us to lead awkward conversations with our white colleagues,” Harper said, to nods of recognition from many in the audience. “That’s despite the fact that people of color are often in the least powerful, lowest-paid roles in their organizations, so you’re placing the burden of expectation on people of color who are in a very precarious position.”

The title of Harper’s talk was phrased as a question—“Racial Equity Through Raceless Policy Making?”—but he quickly left no doubt about the answer.

Many states have approached their higher education policy making over time by playing down if not ignoring the role of race, and “data across the decades will show a consistent and persistent pattern of negligence and harm inflicted on specific populations” as a result, he argued.

“Most of the existing policies in our states were created by white folks,” he said.

Too many states still approach their policy making in a raceless way today, Harper said. He then got personal, scanning a room that, like many gatherings of higher education leaders, was filled largely with white faces. “I don’t know that a room that doesn’t have more significant representation of [minoritized] people can say what’s best for people of color.”

Harper acknowledged another reason why his audience might be inclined to minimize the role of race: “I understand you work in a political context,” Harper said, specifically citing the “stupid” and “uninformed attacks” on critical race theory unfolding in numerous states as one trend that might dissuade officials at a state higher education agency from leading with race in policy discussions.

Ultimately, though, Harper said, states can’t expect to overcome significant racial inequities in access to and success in higher education through race-neutral policies. They must develop a specific racial equity strategy, which is likely to include investing to overcome historical inequity and other harms, looking at their existing policies through a “prism of racial equity,” and holding themselves accountable for “demonstrable progress on racial equity, as we do for other key performance indicators.”

The audience responded positively to Harper’s challenge to them, rewarding him with a standing ovation. But in conversations after his speech and over lunch, several attendees spoke of the political realities they faced in their states as an “elephant in the room,” as one put it.

At a time when elections are seemingly being won and lost in part because of “bogeymen” such as the teaching of critical race theory in public schools, as happened in Virginia this month, state higher ed leaders might lack incentive to push a race-specific agenda, more than one SHEEO attendee said.

Asked about that response later, Harper acknowledged that perspective and cited a concept embedded in a course he is teaching this fall on, yes, critical race theory: Derrick Bell’s notion of “interest convergence.”

“Even in politically conservative states and environments that are hostile to race consciousness,” Harper said, “very skillful policy makers and those who are responsible for informing policy can help [white Americans] understand how they will benefit” from race-based policies and investment in racial justice.

Ultimately, though, persuasion may also require state leaders to realize that “people of color are your constituents, too,” Harper said. “We have to get beyond zero-sum thinking.”