Free Download

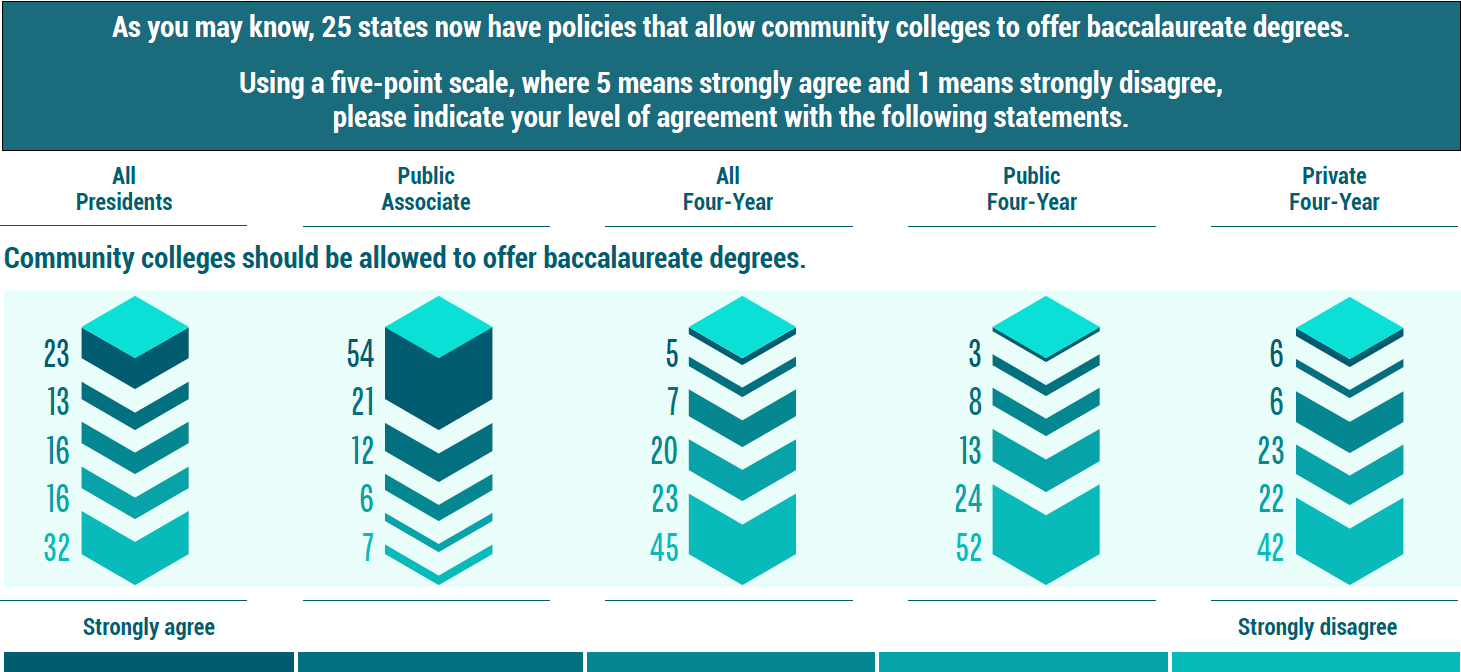

Community college and university presidents are sharply divided over whether two-year institutions should offer bachelor's degrees, a new Inside Higher Ed survey finds.

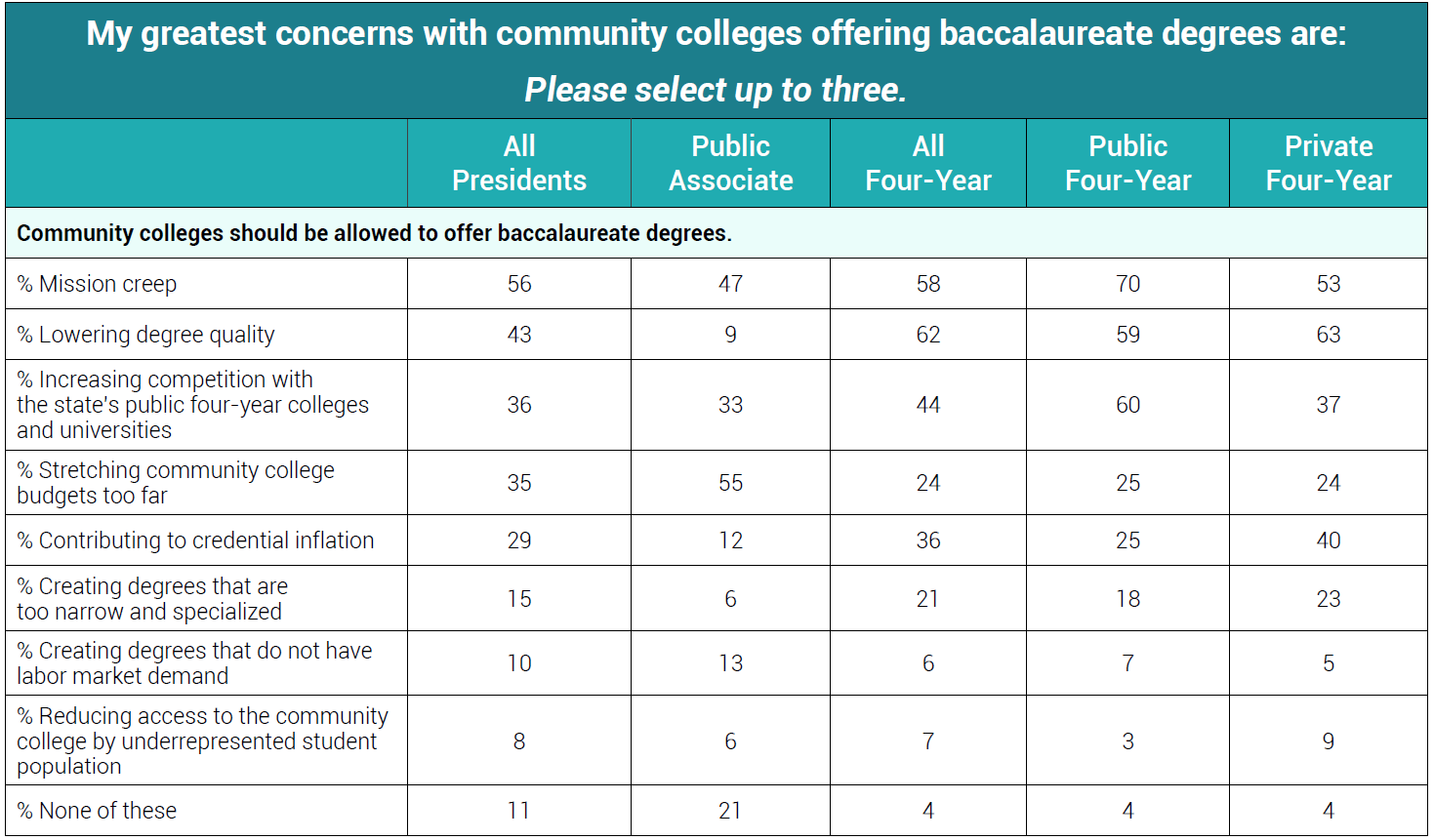

Two-year college presidents want to offer more bachelor's degrees because they believe such programs would help close racial, ethnic and economic gaps in degree attainment. But four-year college presidents are skeptical of the idea and have fought against proposals that would increase bachelor's degree availability at community colleges. They are concerned about the quality of a bachelor's degree from a community college and see the push as evidence of mission creep.

This is among the key findings of Inside Higher Ed's 2019 Survey of Community College Presidents, which you can download free here. The fifth annual survey, released today in advance of the annual meeting of the American Association of Community Colleges and conducted by Gallup, is based on responses from 235 two-year college leaders. (Responses to some questions come from a larger pool of 784 respondents to Inside Higher Ed's Survey of College and University Presidents.)

More About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's Survey of

Community College Presidents was

conducted in conjunction with Gallup.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key

higher ed professionals on a range of

topics.

Inside Higher Ed's editors will discuss

the report's findings and themes in a

free webcast on Tuesday, May 7.

Register for the webcast here.

The survey was made possible in part

by the financial support of Cengage

Learning and Jenzabar.

The community college presidents' survey also found that many of these leaders believe that the push to make all public higher education free would hurt their institutions. These presidents say they face an increasingly complex set of challenges such as declining enrollment, shrinking budgets and a lack of clear transfer pathways to universities as pressure builds from lawmakers and their communities to improve graduation rates.

The Inside Higher Ed survey asked a broad set of questions about community college bachelor's degrees at a time when half the states have now enabled two-year institutions to award such degrees.

The survey found that 75 percent of community college presidents would like to see their campuses offer bachelor's degrees, even though only one in 10 reported offering four-year degree programs on their campuses. Only 1 percent of respondents said their college offers a wide range of four-year degree programs.

Eighty percent of community college presidents agreed that their institutions are in a strong position to offer bachelor’s degrees to students who would not otherwise have access to those degrees because of four-year universities' higher costs or distance from where students live.

Joyce Ester, president of Normandale Community College, in Bloomington, Minn., said individual colleges in the state would not be opposed to offering bachelor’s degrees, but they would have to be programs that meet local employment and economic needs. The state doesn't allow community colleges to award four-year degrees, according to research from New America.

“Across the country students should have the ability to gain baccalaureate degrees in a cost-effective way that fits their situation and still meets all the academic expectations of their programs,” Ester said. “It would have to be program-specific degrees -- it shouldn’t be carte blanche.”

Sixty-eight percent of the presidents surveyed at public and private four-year institutions disagreed with the idea that community colleges should be allowed to offer bachelor’s degrees. Only 12 percent of four-year presidents support the idea.

Many of the four-year college presidents surveyed, 47 percent, also disagreed with the belief that the educational attainment gap between racial groups could be narrowed if community colleges offered four-year degrees. Opposition to four-year degrees at community colleges came mostly from presidents of public four-year institutions.

Wyoming in March became the latest state to allow community colleges to offer four-year degrees. But the community colleges faced opposition from the state’s only four-year institution, the University of Wyoming.

Laurie Nichols, president of the University of Wyoming, said in an email that the state does not have the population to support "eight college universities," which is how she describes UW and the seven community colleges that will now offer bachelor's degrees.

“We can learn from surrounding states that have created too many four-year colleges -- also on spare populations -- and struggle to support them,” she said. “This move would also create extensive duplication of programs, courses and faculty. Duplication is very costly to a state.”

Before passage of the bill granting Wyoming community colleges access to four-year degrees, Nichols called for more time to research the issue and said the university was willing and ready to collaborate with community colleges.

Twenty-six states currently allow community colleges to offer at least one bachelor’s degree program, said Mary Alice McCarthy, director of the Center on Education and Skills with the education policy program at New America, a Washington think tank. (See related essay by McCarthy here.)

“As states try to increase the rate of bachelor’s degree attainment, everyone is depending more and more on community colleges to get the job done,” McCarthy said. “Right now, we’re depending on the system of transfer, so why don’t we just be more direct about it? Rather than having students chase after a bachelor’s degree and go through a terrible transfer process … allow them to finish the degree where they start.”

McCarthy said offering bachelor's degrees in Wyoming community colleges makes sense because many people live in parts of the state without access to a four-year public institution.

"We do need to be careful we're not just chasing cheap degrees," she said. "We need to make sure these are high-quality degrees, and we need a work-force focus. But I don't think there is any reason to believe that a Miami Dade College or a Broward College can't produce a high-quality bachelor's degree program."

Although more than half of states allow community colleges to offer four-year degrees, each state varies on how broad those programs can be. Michigan, for example, passed a bill in 2013 that allows community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees only in cement technology, maritime technology, energy production technology and culinary arts. State lawmakers have since regularly introduced new bills attempting to expand the types of four-year programs the community colleges can offer. Those proposals have so far failed to make it through the Legislature.

“In a state that has one of the top forecasted declines in high school population in the country, with 15 public universities and 40 independent colleges, it makes absolutely no sense to create, convert and vastly expand the missions of our community colleges,” said Dan Hurley, chief executive officer of the Michigan Association of State Universities.

Hurley noted that many Michigan universities already offer bachelor’s degrees at satellite centers located on community college campuses. About 5,030 students are enrolled in these four-year degree programs, and 1,452 bachelor's degrees were awarded to these students between 2017 and 2018, he said.

The state also has more than 760 transfer agreements between two- and four-year institutions, Hurley said.

“It would really strike me as being unhelpful to convert the community colleges into direct competitors as opposed to extensive collaborators,” he said.

Ester, the Normandale president, said her campus has a similar arrangement with three universities offering bachelor’s degrees on their campuses. Normandale has about 14,000 students, 860 of whom are enrolled in one of the 14 bachelor’s degree programs offered by the three universities.

Transfer as a Barrier

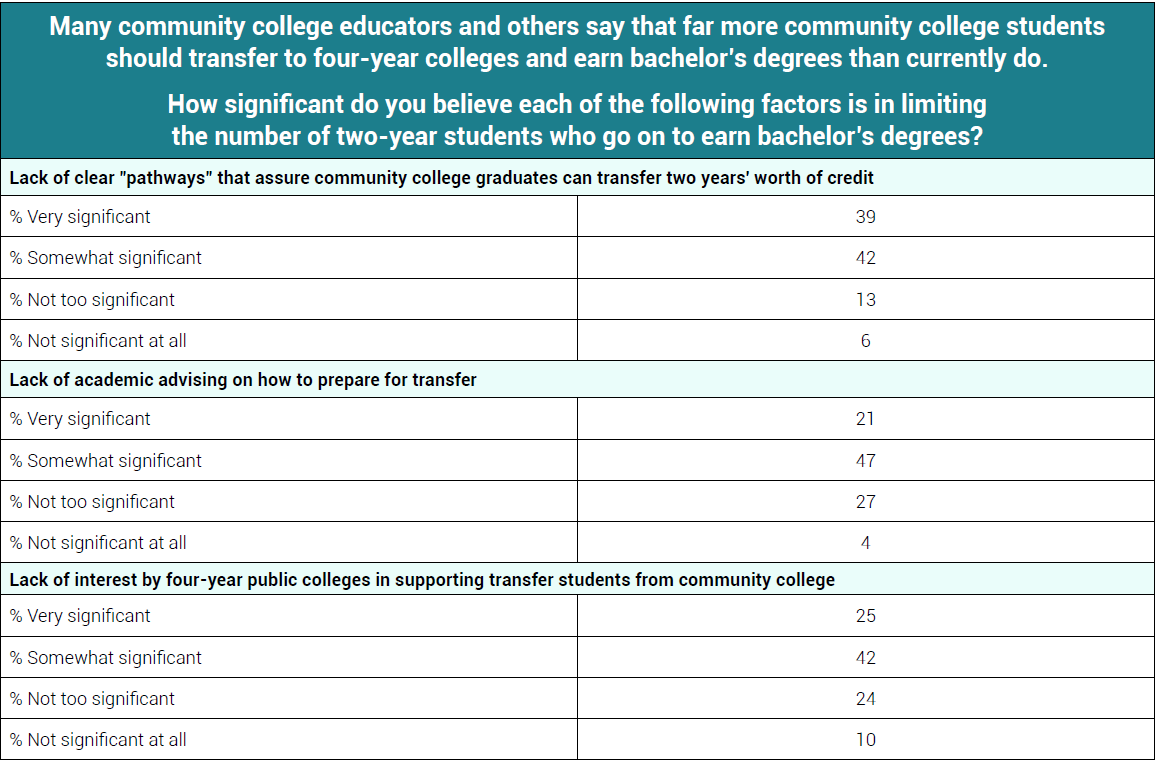

One reason community colleges want to offer more bachelor's degree program is that transfer barriers remain a challenge for students, McCarthy said.

Eighty-one percent of the community college presidents surveyed by Inside Higher Ed said the barriers were significant. And 67 percent of two-year presidents said a lack of interest by public four-year colleges prevents students from transferring from community colleges to universities. Fifty-seven percent of community college presidents said there is little interest from private four-year institutions to build transfer pathways to those institutions.

“Transfer works in some places,” McCarthy said. “But every study around transfer shows significant credit loss when students make the move.”

A Government Accountability Office study released in 2017 found the average transfer student lost a full 43 percent of their credits, or about 13 credits, which is the equivalent of a semester of course work.

McCarthy said some of the best transfer partnerships between two-year colleges and universities exist in Florida, which also allows the community colleges to offer four-year degrees.

“Valencia College and the University of Central Florida do work well together, but Valencia also offers bachelor’s degrees,” she said. “That hasn’t ruined anything for UCF. We don’t want Valencia and the other colleges to duplicate things like liberal arts, but there are programs they can do that UCF doesn’t. The Florida case shows this isn’t a zero-sum game, and it doesn’t have to come at the expense of four-year programs.”

Valencia offers bachelor’s degrees in nursing, computer science and business leadership. One in four UCF graduates transferred from Valencia.

Both institutions recognize they’re not going after the same market for students, said Josh Wyner, chief executive officer of the Aspen Institute for Community College Excellence. Valencia won Aspen’s highest community college award in 2011.

“UCF enrollment is growing, and Valencia’s enrollment is growing because people understand they’re not in competition,” he said. UCF enrollment has steadily increased each year from about 56,000 students in 2010 to nearly 69,000 students in 2018, according to the university. Valencia enrolled about 41,300 full- and part-time students in 2010. In 2017, the full- and part-time student enrollment totaled more than 45,500.

Free College vs. Tuition-Free Community College

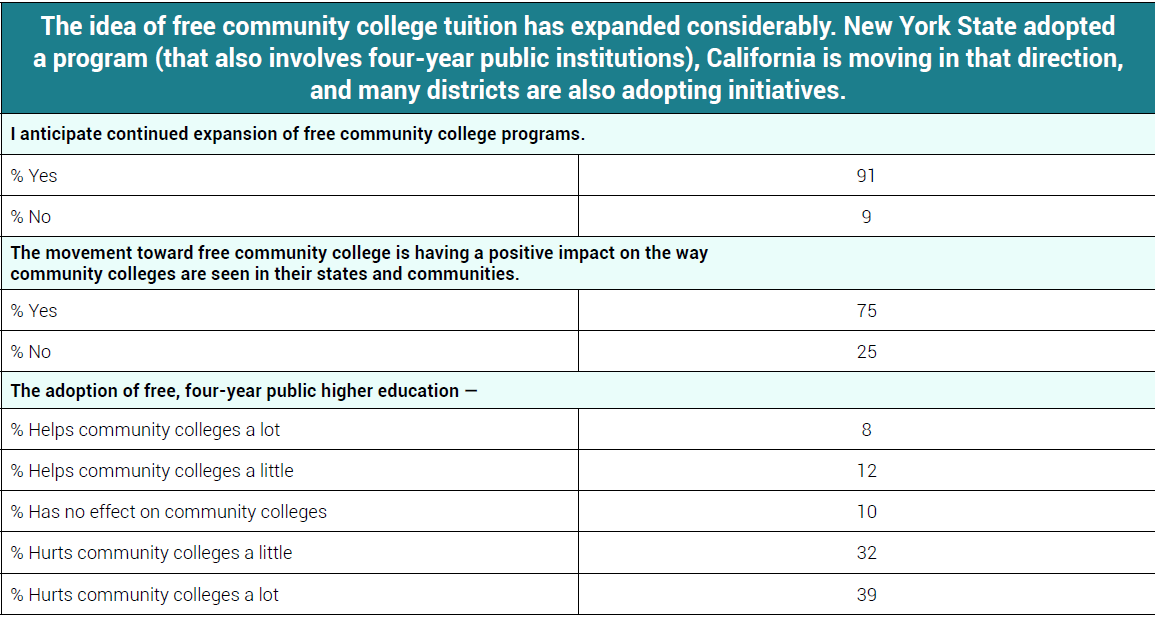

The survey also found that nine in 10 community college presidents overwhelmingly expect to see free community college expand across the country. They believe the free-college movement also has a positive impact on the way two-year colleges are perceived by the public.

“Free community college is more appealing because it’s less expensive, but people also view community colleges as open access, more accessible and more in the community and attached to work-force programs,” said Wesley Whistle, an education policy adviser at Third Way, a center-left think that has consistently opposed free-college proposals.

But community college presidents worry that calls for free four-year college hurt their efforts to expand free-tuition programs at two-year colleges. Seventy-one percent of surveyed community college presidents believe free four-year college hurts their institutions.

"There are better ways to address the affordability problem than free college,” Whistle said. Third Way has recommended tripling the size of the Pell Grant award and building federal-state partnerships that incentivize states to reinvest in their college and university systems.

Wyner said the "devil is in the details" when it comes to tuition-free community college programs, but he ultimately supports these programs and their ability to make college more affordable for students.

Recent polling by the Campaign for Free College Tuition found support for state governments, instead of Congress, to create tuition-free programs. Respondents to that poll said they supported the idea of free college because of successful tuition-free community college programs in states such as Tennessee and Rhode Island.

Whistle said even though free community college programs are looked upon more favorably, depending on how they are crafted, they still may not help low-income students. "Last-dollar" programs, for example, may only cover the costs of tuition and fees after all other federal and state aid is used. Low-income students whose tuition is covered by federal financial aid, such as the Pell Grant, would still have books and other expenses not covered in a last-dollar program, he said.

The proponents of free community college also don't always consider if two-year institutions have the resources to handle an influx of students, Whistle said.

“If students enroll in an underresourced institution, you’re not doing anything to make them better off,” he said. “It’s important for policy makers to understand there is more nuance to this than just tuition.”

Declining Enrollment and Revenue

Seventy-three percent of community college presidents surveyed said a lack of finances continues to be a problem for their campuses. And nearly 70 percent said enrollment management is a big challenge.

“Community colleges are being asked to deliver more degrees of a higher quality to a more diverse population without additional government funding,” said Wyner, Aspen's president.

At St. Cloud Technical & Community College in Minnesota, administrators have been looking for solutions to help students struggling with food and housing insecurity, while also helping the state reach its goal of having 70 percent of adults in the state with a degree or certificate by 2025.

“Students don’t care about transfer when they worry about if they can eat, pay their bills or are depressed,” St. Cloud president Aneesa Cheek said. “We have to get back to really caring and using our financial and human resources to demonstrate in our budgets that we care about students. But that’s not easy … state funding has declined, and federal financial aid hasn’t kept up as much as we’d like. It’s a tight rubber band stretched to the maximum.”

Minnesota is one of 30 states that has a higher per-student state appropriation than it did in 2013 but is still funded at a lower level than it was before the 2008 recession, according to a recent report by the State Higher Education Executive Officers association. Minnesota funded institutions at $8,437 per full-time equivalent student in 2008. As of 2018, that figure had decreased to $7,758.

Many community colleges that relied on adult learners to fill classroom seats, in addition to traditional high school graduates, have been hurt by enrollment declines. Older adult learners in particular are less likely to enroll when the economy is performing well.

The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education projects the number of high school graduates to remain flat from now until 2023 and to decrease after 2025 from about 3.5 million graduates per year to about three million.

“Enrollment is always going to be a significant issue, because we’re in the people business and the education business,” said Ester, the Normandale president. “A lot of schools are seeing bigger declines, but we’ve flattened off and I’m very grateful for that.”

Enrollment at Normandale was at 7,440 students in 2011 and has hovered around 6,850 students for the last five years, according to the college's data. Ester said the college’s high school dual-enrollment programs have helped stabilize the campus population. From 2011 to 2018, the high school student enrollment at Normandale more than doubled, from 519 to 1,094 students.

Over all, community colleges nationally are operating under different levels of state and local funding while trying to serve different constituents, such as students, faculty and local communities, and being innovative.

“With all of these different things going on, it’s important for us to be innovative,” Ester said. “When you’re worried about keeping the lights on, it’s hard to innovate, but that’s what our students deserve and what they expect.”

Six in 10 community college presidents surveyed said they worry some education reforms expected to improve graduation rates at two-year colleges may not actually increase student learning.

“At the center of our discussions is equitable student outcomes and acknowledging that learning is about quality and rigor,” Cheek, the president of St. Cloud, said. “It’s not about how do we change the student, but how do we change, through pedagogy and practice, our systems and policies?”

The challenge and expectation are that community colleges will maintain quality, a rigorous curriculum and the overall learning experience for students while improving the way that education is delivered to students, she said.

The Presidential Pipeline

Cheek is one of the newer community college presidents -- she has been at St. Cloud for nine months. There have been concerns over the past decade about filling open presidential positions as many community college presidents reached retirement age.

Fewer presidents surveyed -- 17 percent compared to 26 percent a year ago -- indicated they plan to retire in the next two years. That percentage is smaller because many of those positions have been filled.

In North Carolina, 34 out of 58 presidents started those positions in the past three years, said Audrey Jaeger, executive director of the Belk Center for Community College Leadership at North Carolina State University.

“The issue is [now] less about how many are retiring but how can we prepare current and future presidents for these complex jobs,” she said.

Current community college presidents were also split on whether there is an impressive pool of potential two-year leaders available to take their places.

- 37 percent agreed that there is a strong pool of potential community college leaders.

- 34 percent remained neutral on the question.

- 28 percent disagreed and do not feel there is a strong pool of future leaders.

The presidents who were skeptical of the pool of potential two-year leaders said there are not enough clear paths to the presidency.

- 43 percent of community college presidents agree there are no clear paths to prepare for the presidency.

- 39 percent disagreed and believe there are clear paths.

- 60 percent said there are too few minority candidates for community college presidencies.

- 42 percent said there are too few women candidates.

"We have to go after the talent,” Jaeger said.

At N.C. State’s doctoral program for community college leaders, Jaeger said there are candidates and future students who have the potential to be great leaders, but often they need scholarships to pursue a doctorate or encouragement to pursue becoming a president.

Cheek, who is African American, said she didn’t take the traditional route to become a president. She worked in the corporate sector for about 10 years before taking a position in the president’s office at Sinclair Community College in Dayton, Ohio, and received encouragement from the college's president, Steven Johnson, to pursue the presidential pathway.

Cheek views her role as president as fulfilling the goal she set to help improve her community when she left the corporate workplace.

“If employers say students are not ready, then we've failed,” she said. “If our transfer institutions say they’re not ready, then we’ve failed. Extending how we measure ourselves and hold ourselves accountable has to extend beyond our institutions. We are trying to improve the economic and social mobility for students, and if they’re not able to navigate the next leg of their journey, we have more work to do.”