From Rachel Toor

Last spring, I lost a beloved student to suicide, the first time I’ve experienced that shock and horror in two decades of teaching. Of all the young people that year whose mental health I worried about, that student wasn’t even in the top five.

At the time, I reached out to some presidents, because it occurred to me that providing pastoral care to their communities was part of the job I hadn’t considered and is impossible to prepare for. Then I tried to stop thinking about that.

A couple of weeks ago, my husband and I attended the celebration of life for our beloved 23-year-old nephew, a sunny Washington State grad who seemed to have it all going on. His death is the unthinkable, the unimaginable.

What I’ve learned is that often the people you most need to worry about are those you don’t think you need to worry about.

We’ve done a decent job at teaching girls to lean in, speak up, and shout out injustices where they see them. They are generally good at seeking help, and even those in Generation P(andemic) are trying to make connections with other humans. Not that they’re OK, of course. The kids are not alright.

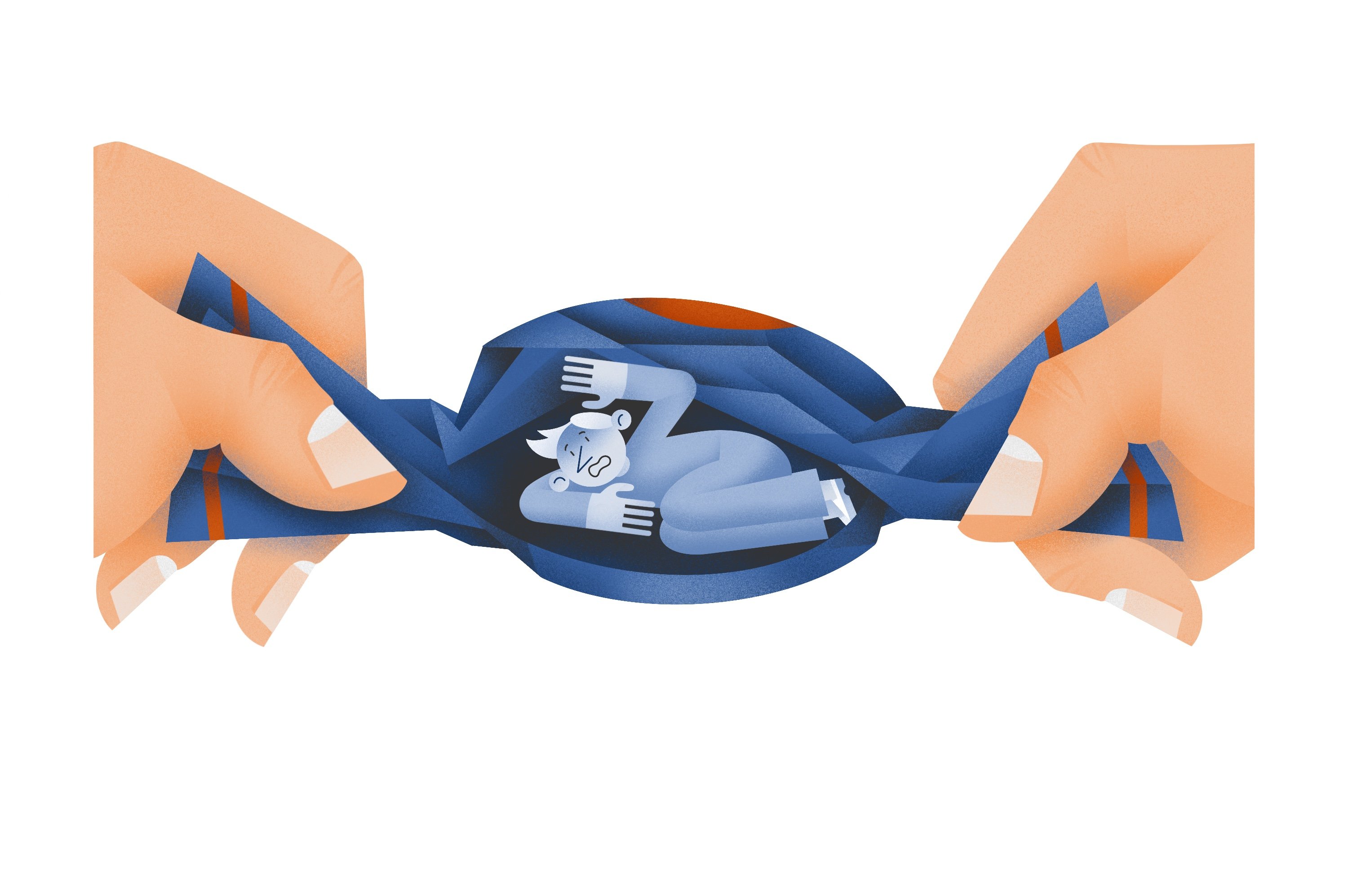

These days, I’m really worried about young men. We know many of them are opting out of college, and when they come, they are in the minority. They’ve been told they’re toxic, the problem, the privileged—even when they are in fact none of those things. We’ve corrected to expand the canon, but this means that they don’t get to see much of themselves in the literature we read.

In truth, at times I have been frightened of some of my own creative writing students, those who are alienated, angry, and craft essays about their rage. They bring knives to campus (I’ve seen them). I’m pretty sure they have guns at home. Often these guys say nothing when their peers talk about which writers we shouldn’t read because they’ve been canceled or how white men are at the root of all evils.

If Mr. Rogers were alive today, I’m pretty sure he’d be in despair. He told us to look for the helpers. I see them everywhere, and they are the kind and generous souls whose mental health I am most concerned about. Selfish narcissists like me are good at making our needs known. (Friends: Pay attention to me!) Givers, like my husband, my nephew, and so many other men aren’t as adept at prioritizing themselves, and they can make it easy for the rest of us not to notice when they’re hurting, scared, or just a little shaky. Sometimes they’re so busy attending to others they don’t even know they need help.

I hope the presidents I know, most of whom are fundamentally helpers, create space for themselves this summer. And I wish they never have to face the situations described by their colleagues in this issue. If only.