From Rachel Toor

The Sandbox is possible because presidents and chancellors trust us with their stories, are willing to write vulnerably about things that matter, and know that our aim is serve and support those leaders who are doing good work. We scrub submissions of identifying details and edit to mask distinctive voices (sadly; there are some darned good writers).

To be clear, we know (or Doug corrects me when I forget) that the people willing to write for us are not typical. There are plenty of presidents who are greedy, craven, and egomaniacal jerks, more devoted to their personal ambition than to the institutions that employ them. Not everyone wants to play in The Sandbox; it's a self-selected group and therefore my view is colored because of who I'm in contact with.

The bulk of our readers are not (yet) at the top spot, but are people connected to and concerned with the future of our industry: VPs, EVPs, AVPs; student affairs staff, college counselors, legal counsel, department heads, librarians, adjuncts, and administrative assistants. We welcome anyone who wants to understand leadership and is willing to pony up a little extra coin to support Inside Higher Ed's free journalism.

Every president or chancellor knows to expect to be held accountable by boards, who know more or less about our weird business, and to have their decisions questioned by faculty, since that is a healthy part of the checks and balances of shared governance. We also know that most faculty want to keep their heads down and focus on their students and research and aren't necessarily informed about the landscape of higher ed outside their own campus gates, if even that.

About congress's understanding of higher ed, especially in light of another shit-show hearing this week, I have this to say: [ ]

But we do expect administrators to know better. They are often privy to details that can't be shared publicly, at least if they're trusted by their bosses. We might expect them to extend a kind of grace to those at other institutions, especially when they've seen first-hand how rarely a whole story gets told in the media

Which is why I was surprised to hear, on a recent webcast, a current provost say about recent campus protests, "A lot of the problems that I see there are judgment issues on the part of senior administration to be honest. So, I have seen a failure of leadership."

He went on, "I am a very pro-student person, and I do not have to feel the pressure from trustees or politicians in the same way, but I do think a lot of senior leadership at universities have definitely caved to external pressure, and instead of trusting the students, I mean, they called in the cops."

Most college leaders have come up through the faculty, and many say working with students is the best part of their jobs. I cannot believe any president who felt the need to bring police to campus did so with anything but a heavy heart and no other options.

After last week's issue, I've heard from leaders of vastly different institutions who said the current president's description of what life had been like resonated, including for those where there has been no real turmoil. I was shocked by how rattled even the most characterologically optimistic and wildly successful presidents are these days and to hear them ask: how can I keep doing this job? Do I even want to keep doing it?

Several presidents told me they have met with students to discuss their demands, and then turned around to meet with community leaders who demanded the exact opposite. One president said, "Students (vilified by some media for protesting) are not even close to being the most difficult consistency when it comes to conflict, anger, and criticism. We can understand adolescents banging a drum. What's harder to make sense of and manage are the parents and alumni who are charging hard, using violent rhetoric, vulgar language, and even making direct threats."

Something to remember: none of what I've been hearing will get reported in the media.

Describing his time as a nurse during the Civil War, Walt Whitman wrote, "Future years will never know the seething hell and the black infernal background of countless minor scenes and interiors, (not the official surface-courteousness of the Generals, not the few great battles) of the Secession war; and it is best they should not—the real war will never get in the books."

The behind-the-encampments real stories will not get in the books. Or in the Paper of Record. Or even into Inside Higher Ed's news pages.

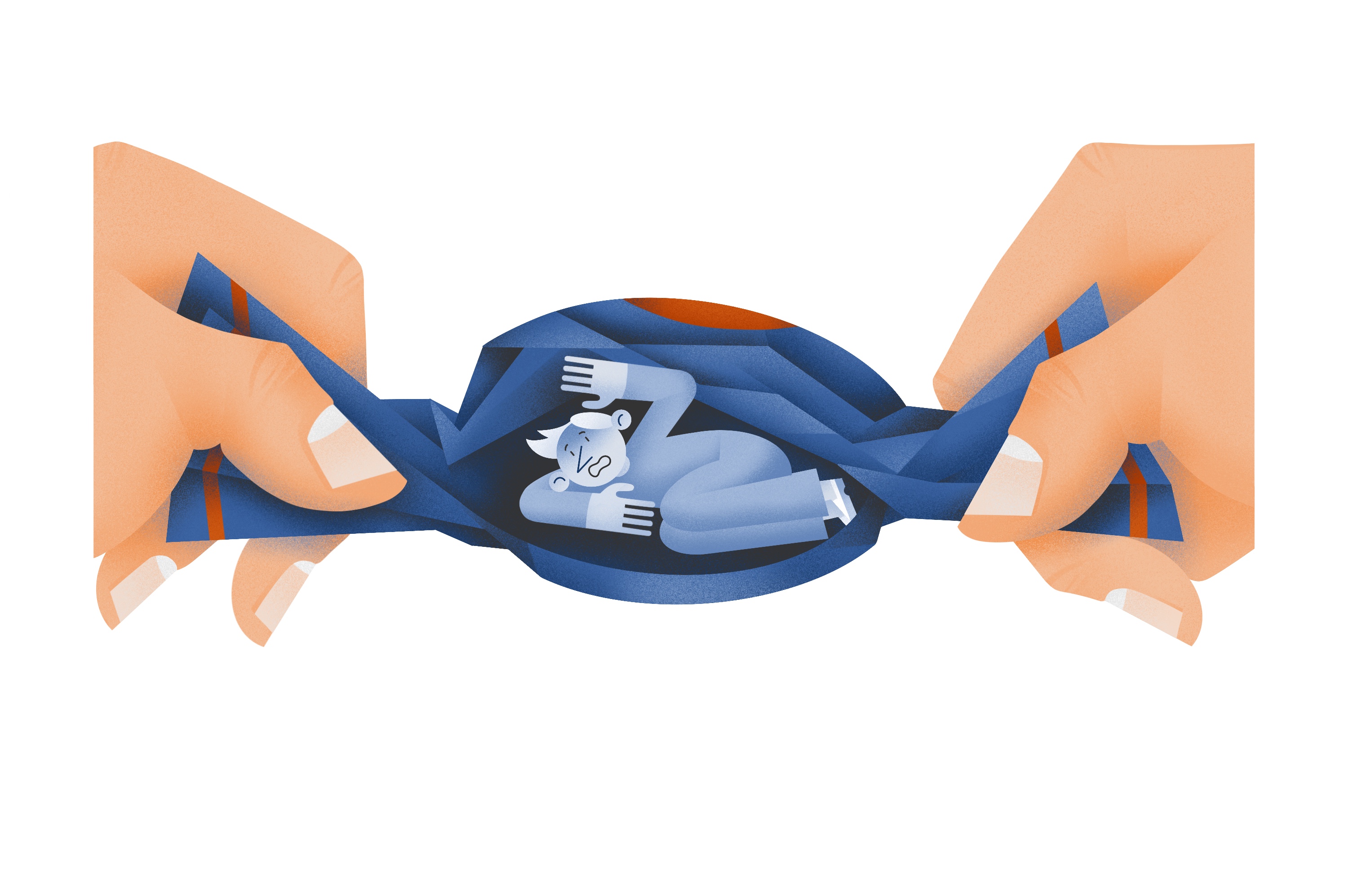

On Sunday I had a conversation with a president ("a very pro-student" person of color who had marched to protest the murder of George Floyd) who said calling in the cops was the hardest thing he'd ever had to do in his career. Still shaken, he went over with me a detailed timeline of how everything had gone down, including bits of information that would never be made public. Even though no one had been even slightly injured, he was haunted by indelible images of police on his campus. I felt guilty even asking him to tell the story because he was still reeling from the trauma of what he knew had been an unavoidable step.

Presidents can never play the victim card; this is what they've signed up for. Or it was. Things that used to just feel difficult and part of the role have become an impossible and often existential struggle. It's easy to critique from the cheap seats. And safe.

To call this a failure of leadership demeans deliberative people who have a deep knowledge of their campus communities, an understanding of the terroir in which particular protests grow, and a commitment to teach and protect their students. These are their students, after all.

Leaders may not always make all the right decisions, but they are doing really freaking hard jobs in impossible times. Higher ed has enough problems without us turning on each other.