You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

To many admissions experts, the gold standard for private college admissions policies is a pledge to be need blind in admissions and to meet the full demonstrated need of all who are admitted. This combination of policies is consistent with telling low-income students that if they work hard, they could be admitted to some of the top colleges in the country and have enough money to enroll. But only a few dozen private colleges have such policies. And this year the College of the Holy Cross ended its long-standing tradition of need-blind admissions.

Holy Cross didn't announce the change.

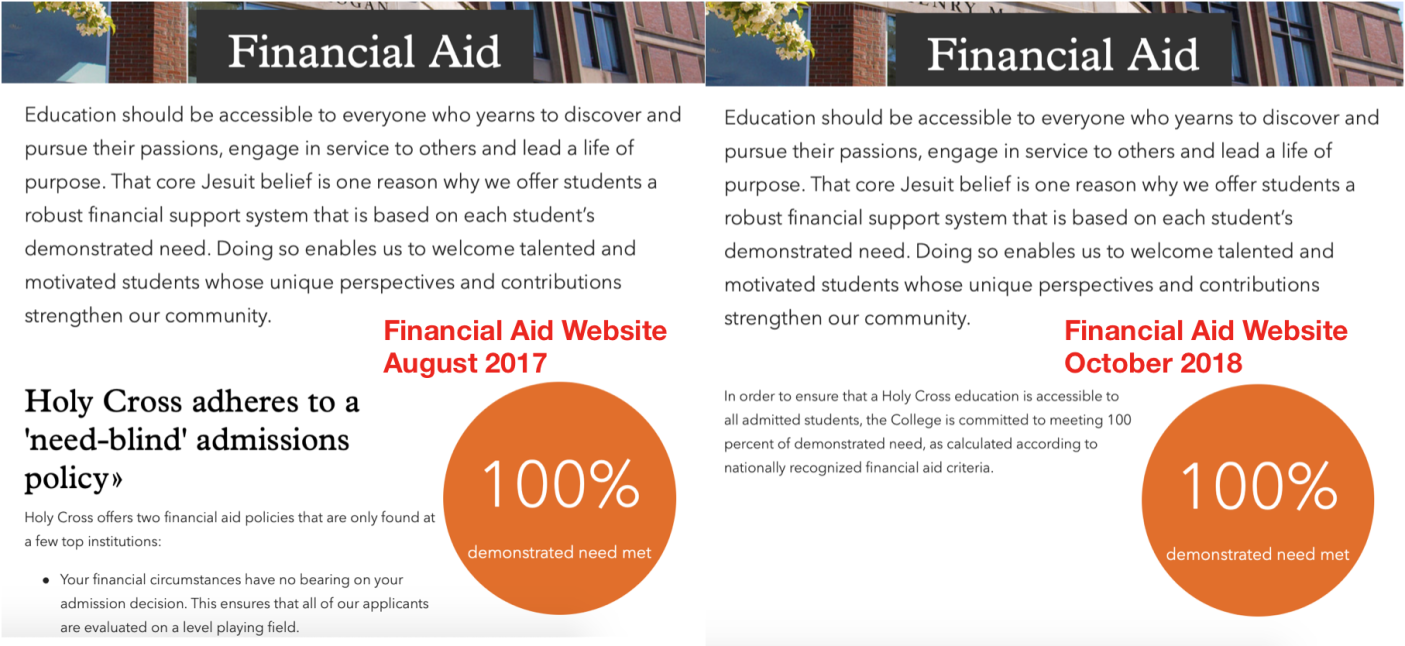

But The Spire, the student newspaper, noticed a change in the financial aid portion of the college's website and ran screenshots (at right) from last year and what the site used for the current admissions cycle. Last year the college boasted about being need blind, but that pledge is gone.

But The Spire, the student newspaper, noticed a change in the financial aid portion of the college's website and ran screenshots (at right) from last year and what the site used for the current admissions cycle. Last year the college boasted about being need blind, but that pledge is gone.

In an interview, Margaret Freije, provost at Holy Cross, said that she supports the values behind need blind, but that it had become unsustainable financially.

The college's financial aid budget had gone up from $49 million in 2014-15 to $67 million this year, and Freije said that the college could not afford such increases year after year into the future.

The endowment at Holy Cross -- $783 million -- makes the college among the wealthier private colleges in the country. But Holy Cross is not wealthy compared to the relatively small number that are need blind. Holy Cross has 2,700 undergraduates. Amherst College, with 1,800 undergraduates, has an endowment of more than $2 billion.

In fact, Holy Cross lacks the endowment of colleges with smaller enrollments that dropped need-blind policies in recent years. Wesleyan University, which dropped need blind in 2012, has an endowment that is just over $1 billion. Haverford College has an endowment of about half that, but with only 1,250 undergraduates. It dropped need blind in 2016.

Here's how Freije said that Holy Cross handled the first year of being need aware.

First the admissions team evaluated the entire applicant pool, admitting those who applied early decision on a need-blind basis. Then the college admitted 1,900 applicants through regular admission. At that point, the funds for the financial aid budget were largely depleted. (Federal data show Holy Cross admits less than one-third of applicants.)

The last step of the process was where Holy Cross changed this year. The admissions team identified an additional 600-700 applicants who were "fully admissible," Freije said. From that pool about 90 were offered a spot. And in that pool, ability to pay was a factor in deciding whom to accept.

"We're trying to be need blind as much as possible in the process," she said.

Freije said it will be impossible to know for some time exactly what the final spend will be on financial aid. Some students change their minds over the summer or submit information about changing financial circumstances.

But she said current numbers suggest that the class will be stronger academically and with more socioeconomic diversity than last year's class. She said it's too soon to predict the final discount rate for new students. But she expects it to be about a percentage point higher than last year's 41.5 percent.

Part of the motivation to move away from need blind, Freije said, was to offer better aid packages to some low-income students admitted than in the past. She said that Holy Cross has met its stated goal of offering complete aid packages, but that she feared some in the past relied too much on loans and not enough on grants.

Some of the colleges with which Holy Cross competes for students remain need blind. One of the top overlap colleges is Boston College.

John L. Mahoney, vice provost for enrollment management at Boston College, said that, to stay need blind, BC must increase its aid budget each year by more than the percentage change in tuition. The current budget for need-based aid at BC (with more than 9,500 students) is $131 million.

Mahoney said that keeping need-blind admissions is "expensive," but "aligns with our mission and values as a Jesuit university." He said that Boston College wants to "attract and enroll the best students in the country regardless of family income."

Boston College is not unique in having to spend more each year to maintain need-blind admission.

Increasingly, those institutions that are need blind draw attention to the budget impact of such policies. Duke University on Saturday announced that its board had adopted a budget for the next academic year. The operating budget for the university is going up 1.3 percent, while the budget for undergraduate financial aid is going up by 5.9 percent.

Discount Rates Going Up

Officials at Holy Cross noted concerns at many colleges about increasing discount rates. It should be noted that many colleges experiencing higher discount rates are not need blind and many are spending a lot of money recruiting students who may not need aid. But even if they are discounting for reasons other than helping low-income students enroll, the increases are taking a toll on college and university budgets.

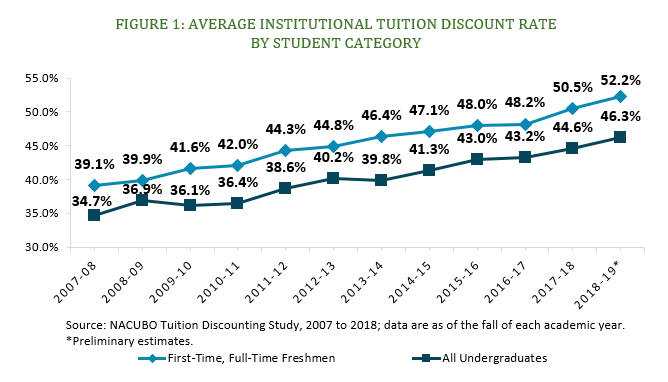

A national study of college tuition discount rates, released Friday, has found that private colleges and universities offered incoming freshmen discounts higher than 50 percent during the last academic year and projects record high discounts this year.

According to an annual study by the National Association of College and University Business Officers, or NACUBO, discount rates surpassed 50 percent in 2017-18 and are on course to hit 52 percent in 2018-19. The rapidly rising rates are the result of continued efforts by colleges and universities to aggressively recruit and retain more freshmen. The trend is occurring as college enrollment is declining nationally and competition for students is intensifying.

The 2018 NACUBO's Tuition Discounting Study, which reports final discounting data for the 2017-18 academic year and preliminary estimates for 2018-19, found that the average tuition discount rate -- “defined as institutional grant dollars as a percentage of gross tuition and fee revenue” -- for first-time, full-time freshmen reached 50.5 percent in 2017-2018 and is expected to jump to 52.2 percent in 2018-19, a new record high.

The 2018 NACUBO's Tuition Discounting Study, which reports final discounting data for the 2017-18 academic year and preliminary estimates for 2018-19, found that the average tuition discount rate -- “defined as institutional grant dollars as a percentage of gross tuition and fee revenue” -- for first-time, full-time freshmen reached 50.5 percent in 2017-2018 and is expected to jump to 52.2 percent in 2018-19, a new record high.

“The discount rate for all undergraduates in 2018-19 is estimated at 46.3 percent, also an all-time high,” the report states.

A full article on the NACUBO report may be found here.

Marjorie Valbrun contributed to this article.