You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In Commissioner Jon Leibowitz NYT quote is the salient point: “While not everything Google did was beneficial, on balance we did not believe that the evidence supported an F.T.C. challenge to this aspect of Google’s business under American law.” "Under American Law …"

Under American law, unlike European, monopoly power does not render an anti-trust claim. Intention use of unfair trade practices is the principal threshold. Microsoft, much reformed since the days of its anti-trust challenges, offers still the best example of old law applied to new businesses: the bundling of its Internet browser with its software to the exclusion of other browsers, and most important, with smoking gun emails that indicated intent through pressure on computer companies to be exclusive in their choice of that software tied to the expectation that this tactic would crush competition. It did. Netscape, the superior technology, lost market share to the point of extinction. And Microsoft, now much wizened from the experience, paid a price financially as well as in reputation.

American anti-trust law dates back to 1890 and the now famous Sherman Anti-trust Act. That Act has had a long and tangled history, not least because it was later used against workers' unions in their attempt to organize and bargain for better wages, hours and conditions. The question we have before us today, in light of the F.T.C.'s decision not to bring any actions against Google after its investigation from the administrative point of view (not the Department of Justice, by the way, which would be the agency to bring criminal actions) is: Does American law, defined in the industrial age at the turn of the last century, provide the necessary and sufficient tools to address "anti-trust" in the information age of the 21st Century?

Think Standard Oil, using every trick in the book -- legal and illegal -- to crush competition and consolidate power. Because the United States had three big car companies and the Depression shifted emphasis from big companies to a lacuna of economic activity to maintain stability overall, the most prominent industry in those years, automotive, skipped us a generation of anti-trust activity. Go next to AT&T -- and read Tim Wu's book if you are really curious -- to learn about the penultimate big one, that is the one before Microsoft. In each case, nota been, including Microsoft, it was about a product as well as a service with the emphasis on the former and the latter in a supporting role: gas stations for oil, telephone service for telephones and software for computers.

You can predict where I am going: the Internet and information economy flips the formula. The service -- search -- is the main game, and the product the outcome of the fundamental business driver. What makes the difference? The whole, search -- Google's principal business, is greater than the sum of its parts of the information economy: computers, network and communications companies, software that run the devices, social norms and business operations mediated through these technologies. The contours of U.S. anti-trust law do not address this flip exactly and the way in which money is made or power accrued in the Internet age.

That idea brings us back to basics. What is the social policy goal of anti-trust? Essentially, it is to preserve a free market defined as one where there is a minimum of competition. Competition acts in the name of the consumer to provide choice and to suppress price, as well as to continuously prime the pump of innovation and economic development. History demonstrated that a free market defined as one without government interference led to the emergence of powerful, exploitative gargantuan companies in railroads, oil or telecommunications. Government, in this case anti-trust law, broke up the "trusts" or cartels that fixed prices, offered the consumer no choice and kept the competition out of the marketplace. From the eighteenth to the twentieth century, government had shifted from the centralized powerful force (think Great Britain) to the referee of the new, great powerful corporations that, for all intents and purposes, dominated twentieth-century global society (think Roosevelt and Taft as "trust-busters"). It took F.D. Roosevelt and the Great Depression to create the foundations of "welfare capitalism" that brought labor reform and social services into the overall landscape of U.S. economy, society and politics.

Let us then set aside the specifics provisions of U.S. anti-trust law and ask the question anew: what impact does Google have on competition for Internet services in this country? Has it created a monolith of services -- search plus all of its other products and platforms -- or is the market still open to competition? How does the user, i.e. consumer, fare in this environment, better or worse in terms of choice, price and buying-power? How is the goal of a free market maintained, or not, in U.S. society by taking no action, especially since taking action can have the boomerang effect of inhibiting business development out of a fear of governmental restraint? At a more granular level the questions revolve around how and in what ways does a search algorithm function in the information economy? How does that function compare to the dynamics of an industrial economy. Do we need to revise the law to achieve the same goal: a free market in the twenty-first century?

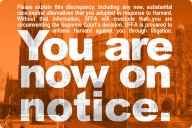

These are the key questions. I do not know enough about anti-trust law or software or Internet economics to propose an answer. European countries do make market share actionable whereas U.S. law makes it only an evidentiary factor in the anti-competition analysis of anti-trust. I leave it to those more knowledgable than me to adjudge whether incorporating market share into the actionable range of U.S. law would make enough of a difference, or whether in this new economy it is a red-herring. All I know is that the F.T.C. finding yesterday in this one case should not be interpreted as the end, but rather the beginning of the discussion.

Want articles like this sent straight to your inbox?

Subscribe to a Newsletter