You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Babson Survey Research Group is ending its influential report on the number of students who study online and how chief academic officers feel about the delivery method, citing a “coming of age” of the online education market.

Yet the 13th and final annual report, released today, shows that perceived skepticism among faculty members toward online education remains, and that many colleges continue to have no interest in online courses.

With the federal government now including distance education students in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, or IPEDS, the Babson Group said it will shift its focus away from estimating how many students take online courses. The group isn’t giving up on research, its co-director Jeff Seaman said, but will discontinue its annual report in favor of interactive publications -- including a new website and infographics -- and in-depth papers on strategy, policy and more.

The Babson Group hinted at that development last year, when it dropped its own estimates of how many students take online courses in favor of the IPEDS data. This year's report is a hybrid, combining IPEDS enrollment numbers from fall 2014 with results of a survey on attitudes and practice the group conducted during fall 2015.

The introduction of the final report, titled “Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States,” notes the inadvertent way in which the report became a barometer of online education attitudes.

“It began when Frank Mayadas of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation posed a simple question: ‘How many students are learning online?’” the report reads. “It was soon evident that no one knew the answer, and, more importantly, that no one was working on getting the answer. We took on the task, one we thought that, while very interesting, would be a one-off, to address a specific question about numbers.”

In an interview, Seaman said the Babson Group may begin to survey people at other links of the academic “food chain,” examining attitudes about online education among presidents and chancellors or pedagogical approaches among faculty members who teach online, for example.

“The questions that we need to answer now are not the ones that we posed back in 2002,” Seaman said. “It’s time for a different design for a different era.”

The original report, published in September 2003, was full of questions. Armed with survey data, the Babson Group set out to answer whether administrators, faculty members and students would accept online education as a delivery method. More than a decade later, some of those questions remain unanswered.

Looking at enrollment numbers, the answer for students is “absolutely,” Seaman said. The original report estimated that more than 1.6 million students took at least one online course in fall 2002, with 578,000 of them studying exclusively online. The most recent IPEDS data, dating to fall 2014, show those numbers have grown to 5.8 million and 2.85 million, respectively. The Babson Group partnered with the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies to analyze the enrollment data.

The answer is not as clear-cut for administrators and faculty members. Between 2002 and 2012, more and more academic officers said online education was a critical part of their institution’s long-term strategy. Since then, however, the share appears to have plateaued at around two-thirds of respondents. Seaman pointed out that the colleges that remain negative about online education are the ones that don’t offer any online courses.

“We’ve basically reached a point where everybody for whom [online education] is important for their institution is fully on board,” Seaman said.

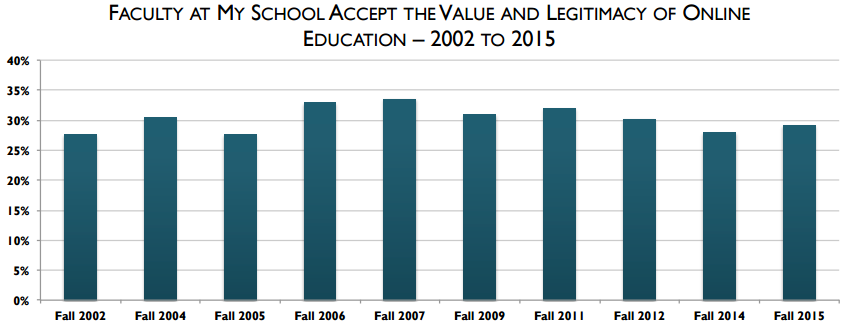

While student enrollments have grown, administrators say faculty members at their institutions remain skeptical about the value and legitimacy of online education. In fact, faculty attitudes have hardly budged over the lifetime of the report.

In fall 2002, about 27 percent of administrators said faculty members accepted online courses as a legitimate method of delivering education. When the Babson Group ran its survey last fall, 29.1 percent of administrators said the same. The report describes that lack of progress as a “continuing failure of online education.”

When the Babson Group worked on the first report, Seaman said, there was an expectation that online courses would “take higher ed by storm.” Other than helping students who may not have been able to physically attend classes pursue higher education, distance education has had “very little impact,” he said.

“For me, the biggest failure is how little change [distance education has] made to higher ed,” said Seaman, adding that colleges could have used online education to rethink pedagogical approaches. “It's a missed opportunity."

After nearly 16 years of surveying academic officers on the same questions, Seaman said he is still surprised by some of the responses. This year, he highlighted the growth rates of the different sectors of online education. Most significant, he said, is the fact that the for-profit sector continues to shrink.

Between 2012 and 2014, for-profit colleges lost 101,045 online students -- a full 10 percent of their online enrollments. Many of those colleges have been forced to close. Private and public nonprofit institutions, in comparison, added 196,054 students. After years of dominating the online education market, for-profit colleges now make up the smallest sector.

Seaman said the Babson Group is still in the process of picking which topics its future in-depth reports will cover. A preliminary version of the website containing the interactive IPEDS data can be seen here.