You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Illustration Photo

A federal rule change that opened the door to more fully online degree programs has not made college tuition more affordable, according to a working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, but at some place-based institutions, enrollment has declined and instructional spending has increased as a result.

The paper, written by David J. Deming, Michael Lovenheim and Richard W. Patterson, explores what has happened in the postsecondary education sector in the years following the removal of the 50 percent rule. The rule change, which occurred in February 2006, meant colleges that enrolled more than half of their students in fully online programs could participate in federal financial aid programs.

At the time, much of the debate centered around what the rule change would mean to the for-profit sector. The paper expands beyond that debate, exploring how competition from online education providers affected the existing market for higher education. More specifically, it looks at the impact of online education in areas traditionally served by one or a handful of colleges that sustained themselves by enrolling local students.

“In a well-functioning marketplace, the new availability of a cost-saving technology should increase efficiency, because colleges compete with each other to provide the highest-quality education at the lowest price,” the paper, which has not yet been peer reviewed, reads. “Nonselective public institutions in less dense areas either are local monopoly providers of education or have considerable market power. Online education has the potential to disrupt these local monopolies by introducing competition from alternative providers that do not require students to leave home to attend.”

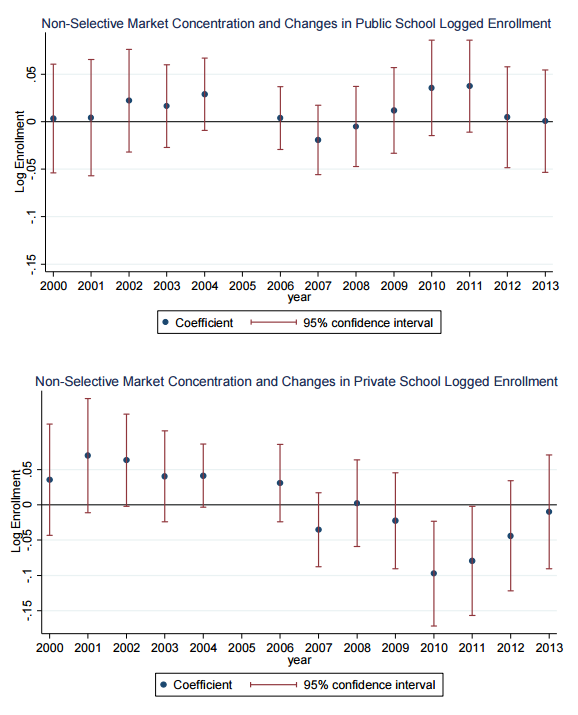

The researchers, who are based at Cornell University, the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the United States Military Academy, used data collected by the federal government’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System to track enrollment, revenue, expenditure and tuition trends between 2000-2013 -- before and after the rule change. They used the data to test three predictions: that competition from more fully online programs would lower tuition rates for face-to-face programs, lead to increased spending on instruction and student support services, and drive down enrollment in areas with low competition between colleges.

The data only provided support for two of those predictions. For one, colleges located in areas with low competition were more likely than others to experience a decline in enrollment. The finding was only statistically significant for less selective private institutions, which saw enrollment declines following the 2006 rule change. Instructional spending also increased at public institutions, though the trend began before the rule change -- perhaps because the colleges were anticipating increased competition from online programs, the paper suggests.

The researchers did not find any evidence that the growth of the online education market lowered the price of tuition for face-to-face programs, however. In fact, at some private four-year institutions in markets with little competition, tuition rates actually increased.

The paper presents two possible explanations why. It could be that private colleges were forced to increase tuition as a result of the enrollment declines that the researchers discovered. Alternatively, the availability of federal grants and loans could be making price less of an issue to students, which could explain why tuition rates didn’t decline.

“This evidence suggests schools likely are not competing over posted prices, which is sensible given the sizable subsidies offered to students through the financial aid system,” the paper reads. “Indeed, if prices are difficult for students to observe, higher competition could cause an increase in posted prices that are driven by university expansions in educational resources.”

Russell Poulin, director of policy and analysis for the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies, said in an email that he agreed with the paper’s findings on the impact of online education in less competitive markets. However, he criticized the paper for assuming colleges are drawn to online education mainly for cost-cutting reasons, as opposed to expanding their market share and serving adult learners.

“Rather than cannibalizing existing student enrollments, online education often serves adults who are time and place bound,” Poulin wrote. “They were not in the market and now are.”

In related news, a separate paper released by the NBER explored enrollment trends in the Georgia Institute of Technology's low-cost online master's degree program in computer science. The study found (as Inside Higher Ed previously reported) little overlap between applicants to the program and the residential program it was based on, suggesting Georgia Tech had tapped into a population of potential students not served by existing master's degree programs.