You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock/Jirsak

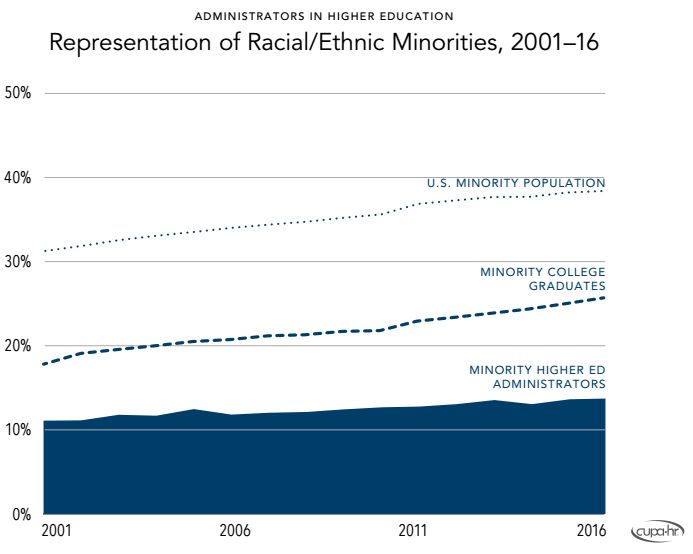

Look only at the trend line showing the slowly climbing percentage of higher education administrative positions held by minority leaders, and it appears colleges and universities are inching toward a day when their leaders reflect the diversity of their student bodies.

But add a few other pieces of data, and a very different picture takes shape. Look at the much faster growth in the proportion of minority college graduates and the growth in the U.S. minority population. It becomes clear that a substantial representation gap exists between the percentage of minority administrators and the makeup of the country. Further, the ethnic and racial makeup of administrators isn’t changing fast enough to keep up with broader demographic shifts -- the line showing the percentage of minority higher education leaders is not growing closer to lines that show the country's minority population or the percentage of minority college graduates.

Those are some key findings in a new piece of research released Wednesday by the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources, CUPA-HR. Researchers reported more equality in salaries, finding that minority administrators are paid equitably on the whole in comparison to white administrators. In fact, minority administrators are paid significantly better in parts of the country where they are less represented, possibly indicating high interest in recruiting and retaining them.

CUPA-HR found that in 2016, 7 percent of higher education administrative positions -- which includes top executives, administrative officers like controllers, division heads, department heads, deans and associate deans -- were held by black staffers. Just 3 percent of those jobs were held by Hispanic or Latino people, 2 percent were Asian and 1 percent identified as another race or ethnicity. The remaining 86 percent of administrators were white.

The percentage of white administrators mirrors that of private industry. In the private sector, 87 percent of senior-level executives are white, CUPA-HR said. That means members of minority groups are underrepresented in both higher education and private industry leadership.

Minority representation among higher education administrations has been slowly rising over the last 15 years. The 14 percent of higher ed administrators in 2016 who belonged to racial or ethnic minority groups was up from 11 percent in 2001.

But that wasn’t enough to keep pace with increases in the proportion of people in the United States who are members of minority groups. They accounted for 38.5 percent of the U.S. population in 2016, up from 30.1 percent in 2001.

Nor did minority representation in higher ed administration increase fast enough to keep up with growth among minority college graduates -- an important benchmark, since candidates need degrees before they can enter the pipeline leading to administrative positions. In 2016, the portion of college graduates who were members of minority groups came in at 26.7 percent. That’s up sharply from 19.1 percent in 2001.

“Increases in the number of minority administrators over time are a false indicator of progress, since increases in the minority population and minority college graduates outpace these numbers,” the CUPA-HR report says.

Different regions of the country showed steady increases in minority representation in administrative positions. The South, however, was more erratic than other regions. Researchers noted that no region showed parity when minority administrative representation was compared to the percentage of minority college graduates.

Breaking down a selection of administration positions by type instead of geography, CUPA-HR found that student affairs chiefs, human resources chiefs and chief legal affairs officers had relatively high levels of minority representation. More than 20 percent of chief student affairs officers were members of minority groups in 2016. In contrast, chief development officers exhibited the lowest minority representation (6 percent).

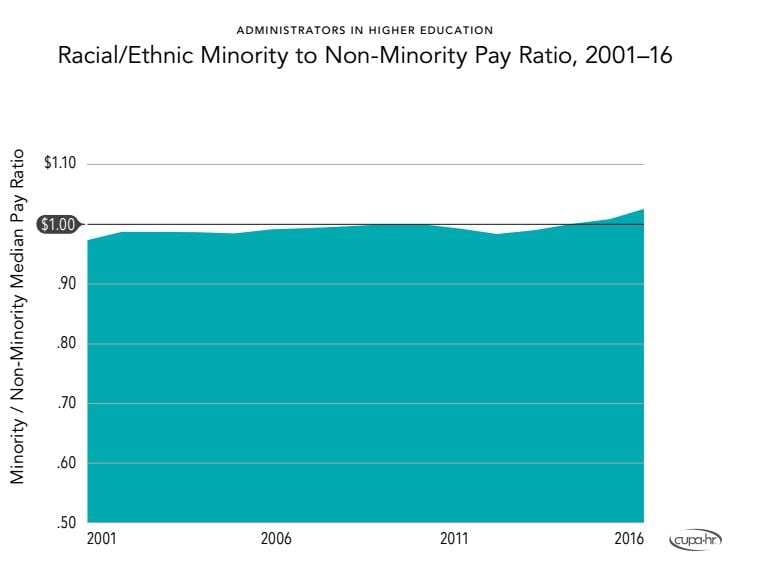

On the question of salary, researchers found that minority administrators' pay essentially matches that of white administrators dollar for dollar. They also noted relatively steady salary equity over the last 15 years, with a slight uptick in minority pay in 2016, due largely to salary increases for Asian administrators.

“Higher education has been really progressive in maintaining that equal pay,” said Jacqueline Bichsel, CUPA-HR director of research. “We were pleasantly surprised to find that.”

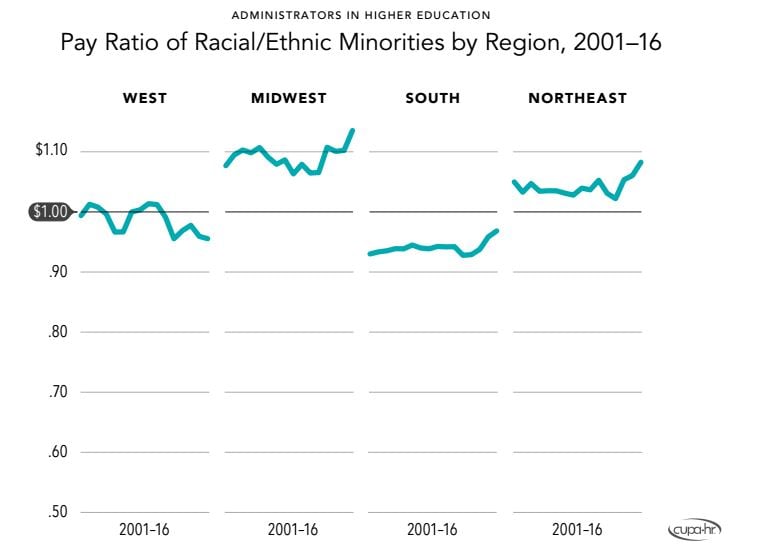

Examining pay by region, CUPA-HR found that the Midwest and Northeast both paid minority administrators more than nonminority administrators in 2016. Minority administrators earned more than $1.10 on the dollar in the Midwest and just under $1.10 on the dollar in the Northeast. In contrast, the West and the South both paid minority administrators about 95 cents on the dollar. That means pay for minority administrators is highest in the regions where colleges and universities have the lowest levels of minority administrators.

Over time, minority administrator pay ratios have been on the rise in all regions but the West, where it has fallen amid some significant swings. The increases reflect higher salaries for Asian, black and Hispanic administrators.

Minority administrators’ pay ratios varied by type of position, but many senior positions CUPA-HR broke out showed administrators who were members of racial and ethnic minority groups receiving higher pay than those who were not. Minority chief legal affairs officers earned less than their nonminority counterparts. Minority library administrators and human resources officers had the highest pay ratios, approaching $1.25 on the dollar.

The findings largely line up with findings in another study CUPA-HR released last month on pay and representation gaps between male and female administrators: scarcity generally leads to higher rates of pay.

“That is the common thread that goes throughout all of this data,” Bichsel said. “It really is conforming to a hypothesis that whenever people see fewer of whatever demographic characteristic -- you see fewer women in a position or fewer minorities in a position -- the response is to attempt to retain those minorities in that position and to pay them more.”

But the report released Wednesday ends by pointing out that equal pay does not compensate for unequal representation for minority administrators. It called on college and university leaders to study whether gaps exist in their own institutions and consider whether they need to make changes to their career pipelines or retention efforts.

“There are things you can do to increase retention and to make people feel included at institutions,” Bichsel said. “It’s not just about increasing diversity, but about increasing inclusivity, which are different things. You have to make people want to stay. That includes creating a culture where they want to stay, and that is very nuanced.”

.JPG)