You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

The ripple effects of large-scale job losses linger for years and can keep adolescents from attending college later in life, according to new research carrying significant ramifications for policy makers, college recruiters and counselors.

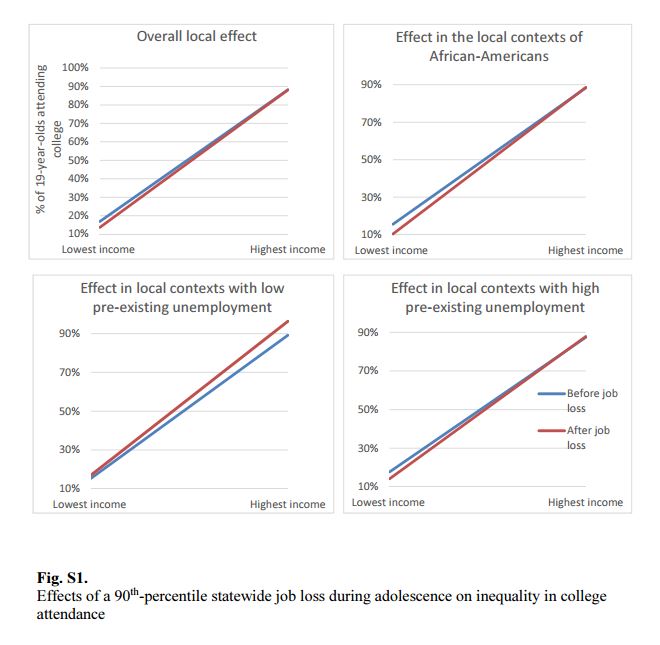

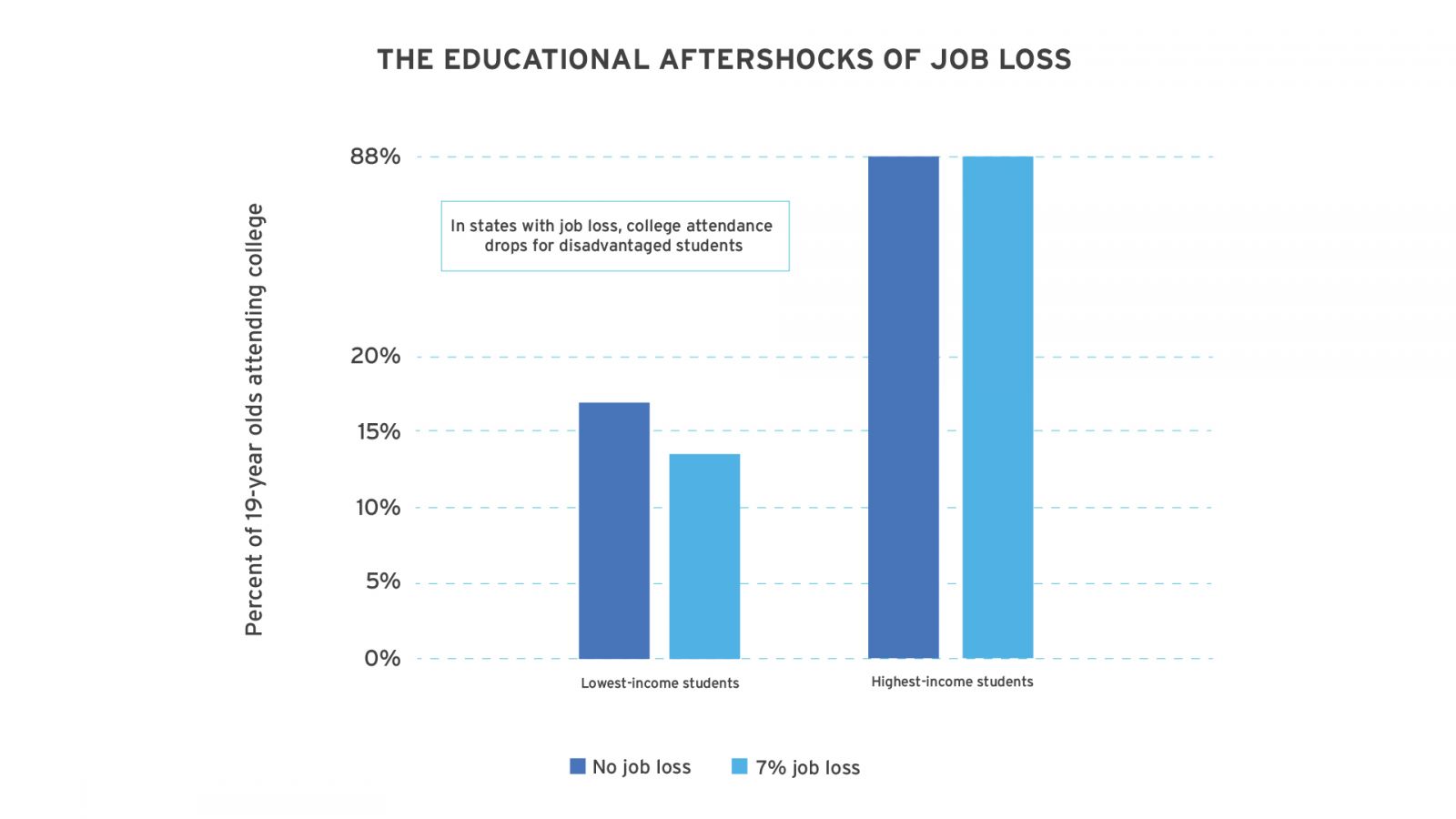

Poor middle school and high school students who live through major job losses in their region attend college at significantly lower rates when they are 19 years old, according to new research published in the June 16 issue of the journal Science. A 7 percent state job loss when a student is an adolescent is tied to a 20 percent decline in likelihood that the poorest young people will attend college.

Local job losses hurt adolescent mental health, researchers found. Job losses also cut academic performance. The negative impacts are not limited to children from families where parents lost jobs -- they extend to those who witness their friends, neighbors and others in the community being affected by layoffs.

The effects are particularly strong among students from the poorest families and among African-American students. Those students have the lowest levels of family wealth to fall back upon when they lose a job and the income it brings. African-Americans also tend to face the highest barriers to employment.

Researchers argue that large-scale job losses are not simply economic events touching directly affected families. They are community-level traumas, said Elizabeth O. Ananat, an associate professor of public policy studies and economics at Duke University who is one of the lead authors of the paper appearing in Science.

“Worse mental health and worse test scores, they are all going to be blows to you that knock you off the path,” Ananat said. “That was a difficult path to begin with.”

The findings shed important light on the fate of communities and young students affected as new technology and globalization brought economic upheaval and blue-collar job losses in recent decades. The research should also carry weight for colleges and universities, which are expected to have to recruit increasing numbers of poor and minority students as income inequality rises and the population of prospective students grows increasingly diverse in coming years.

“High-income kids are largely going to go to college regardless,” said Anna Gassman-Pines, another of the paper’s authors who is an associate professor of public policy, psychology and neuroscience at Duke.

“Where we’re really seeing this decrease is concentrated among the lowest-income kids,” Gassman-Pines said. “That’s increasing inequality.”

Many college leaders argue they need to attract students by making a better argument for the value of higher education. That outlook aligns with the predominant economic theory for how a middle or high school student who has experienced job loss in the community should rationally act.

In the economic theory, a student may have watched their father lose his job when a mine closed. Or they watched a friend’s mother be laid off when the local factory downsized. Those students should then be drawn to a college education because of the promise of larger financial returns and more stable employment in the newly developing knowledge economy.

In other words, economic theory has tended to focus on the idea that a shrinking pool of blue-collar jobs increases the relative return on investment of a college education. But it’s not working that way in the real world.

“Economists tend to think about it as a change in relative prices -- the return changes,” Ananat said. “They miss the fact that it’s an emotional blow, like another kind of community trauma would be.”

Researchers analyzed statewide job losses from 1995 to 2011. Their data included all 50 states. They also examined data on educational mobility that show how much a person’s college attendance at the age of 19 is predicted by their parents’ income.

They found no evidence that families moving out of depressed areas in response to job losses impacted their results. Nor was lost family income enough to explain the drops in students’ educational mobility. Variations in state college tuition levels did not change the effects of job losses on students’ attendance.

“It’s not to say that affordability isn’t an issue,” Ananat said. “We’re saying it’s not the mechanism by which job losses drive inequality.”

Researchers did find that job losses to 1 percent of the working-age population decreased eighth-grade math achievement test scores. The effect was too large to be limited only to students whose parents had lost their jobs. An indirectly impacted group experienced learning losses about one-third of the size of losses among children whose parents lost jobs, they found.

Similar effects were found for students’ mental health -- those affected by job loss showed poorer levels of mental health. The effects of job losses on mental health were most pronounced among young African-Americans, whose reported thoughts of suicide increased by 2.33 percentage points in response to statewide job losses. Again, the change was too large to be prompted only by those whose parents had experienced job losses.

“This is not a story where there needs to be two sets of solutions for some imagined different set of problems,” Ananat said. “Whether you’re from France or Nebraska or Baltimore, this is a traumatic thing that is happening to everybody who is not sort of in this robust knowledge economy.”

There is evidence that the negative effects of job losses are blunted by other jobs being readily available. College attendance is higher across income levels after job losses in states with low unemployment levels, researchers found. Declines in test scores and mental health were also smaller.

Researchers suggested exploring policies like rigorous job training for workers receiving unemployment compensation. They also suggested evaluating whether re-employment policies can soften the effects of economic disruption on student outcomes.

For colleges, the findings could affect recruiting in areas experiencing economic upheaval, Ananat said. She also said colleges may want to explore additional outreach to students who have been affected by job losses. “It’s understanding the experience of kids who aren’t the stereotypical college student,” Ananat said. “It’s not just money.”

The findings could also indicate more investment is needed in local community colleges and states’ nonflagship institutions, particularly those located near areas hit by job losses. Students tend to go to local institutions.

The research could have additional ramifications for colleges after students arrive on campus, Gassman-Pines said.

“Certainly mental health on college campuses is a really big issue right now,” she said. “Job losses in those communities may not be on the radar.”