You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Is it peer reviewed? A yes generally means that some experts, somewhere, think a given piece of research represents the best in its field. But a new study of peer-review processes within political science found that the majority of accepted papers will be evaluated by the average reader as below a journal’s publication standards.

The study, which looked at multiple systems of peer review using computational simulation, also found that all such systems allow random chance to play a strong role in acceptance decisions. A peer-review system in which an active editor has discretion over publication decisions (and does not rely solely on reviewer votes) can mitigate some of those effects, however.

“Does Peer Review Identify the Best Papers? A Simulation Study of Editors, Reviewers and the Scientific Publication Process” was written by Justin Esarey, an associate professor of political science at Rice University, and published this month by PS: Political Science and Politics (yes, it was peer reviewed). Esarey doesn’t allege that peer review is broken, but lists some of its documented shortcomings: it can miss major errors in submitted papers, leaves room for luck or chance in publication decisions, and is subject to confirmation bias among peer reviewers. Given those factors, he says, it’s “natural to inquire whether the structure of the process influences its outcomes.”

Since journal editors can choose the number of reviews they solicit, which reviewers they choose, how they convert reviews into decisions, and other aspects of the process, Esarey continues, “Do these choices matter, and if so, how?” It would be helpful for editors and authors in political science to know which practices -- if any -- improve a journal’s quality, the study says; it defines quality of a single publication therein as the average reader holistic ranking relative to the distribution of other papers.

Esarey relies on some assumptions, including that an editor solicits three blind reviews for each paper. He further assumes that editors assign papers to reviewers at random, conditional on expertise, and that potential reviewers' refusal has nothing to do with a paper’s quality. His computer model explicitly includes multiple reviewers with different but correlated opinions on paper quality and an editor who actively makes independent decisions using review advice, or an editor who merely follows the up-or-down votes of reviewers.

System of Peer Review

The study looks at four peer-review systems for acceptance to a journal: unanimity among votes (in which all three reviewers have to approve of a paper for publication); majority approval among reviewers; majority approval with editor’s participation as a fourth voter; and unilateral editorial decision-making based on reviewers’ substantive reports -- ignoring their votes.

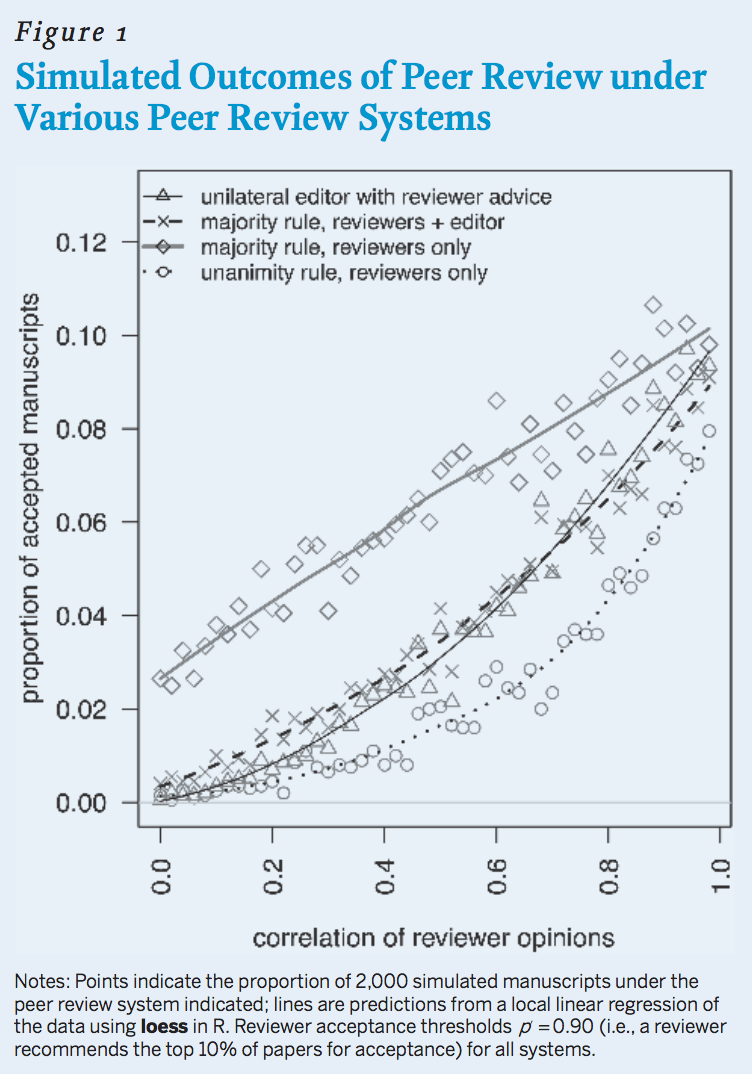

Esarey began his analysis by looking at how each system corresponds with journal acceptance rates, based on a simulation involving 2,000 papers. He found that the probability of a manuscript being accepted is always considerably less than any individual reviewer’s probability of submitting a positive review.

Source: Justin Esarey

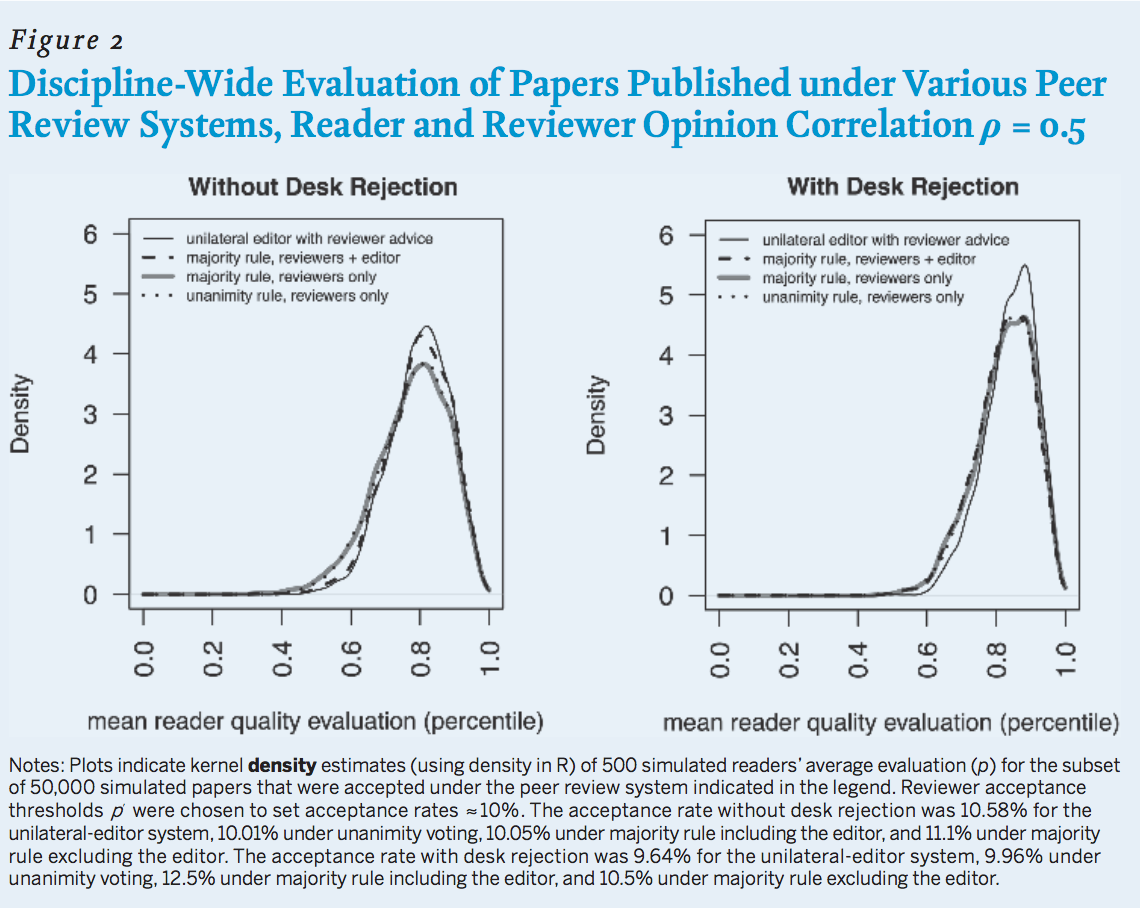

Esarey next wanted to know whether peer review would accept the best papers, based on disciplinary standards, despite mixed opinions from reviewers. He conducted a simulation similar to the first, but with a much bigger population of 50,000 papers and 500 readers, with a journal acceptance rate of about 10 percent. He then computed the average reader rating for all papers that were accepted for publication, and plotted the distribution of these values.

He ran the simulation twice, once for every review system as described and again under a system when the editor rejects half of all submitted papers before sending them out for review; the editor in the simulation rejected any paper deemed worse than the median paper in the population.

All systems produced distributions of published papers centered on a mean reader evaluation near 0.8, or the 80th percentile. So under every peer review system, a majority of papers were perceived by readers as being below that 10 percent threshold. A significant share of the published papers also had “surprisingly” low mean reader evaluations under every system, according to the study: approximately 12 percent of papers published under the majority voting system without desk rejection had reader evaluations of less than 0.65. That means that the average reader believes that such a paper is worse than 35 percent of other papers submitted.

That result is "surprisingly consistent with what political scientists actually report about the American Political Science Review, a highly selective journal with a very heterogeneous readership," Esarey says.

The best-performing system in the study was the unilateral editor decision system without desk rejection, meaning all papers were read by reviewers but the editor had final say about publication: just 6 percent of papers published under that system had reader evaluations under 0.65 (meaning that just 6 percent of papers were believed to be worse than 35 percent of other papers in the simulation population). If editors desk rejected 50 percent of papers under the unilateral editor system, that share fell to 1 percent.

Esarey notes that this system is similar to ones in which reviewers provide a qualitative written evaluation of a paper, but no up-down vote is taken (or where such a vote is ignored by an editor).

Room for Improvement

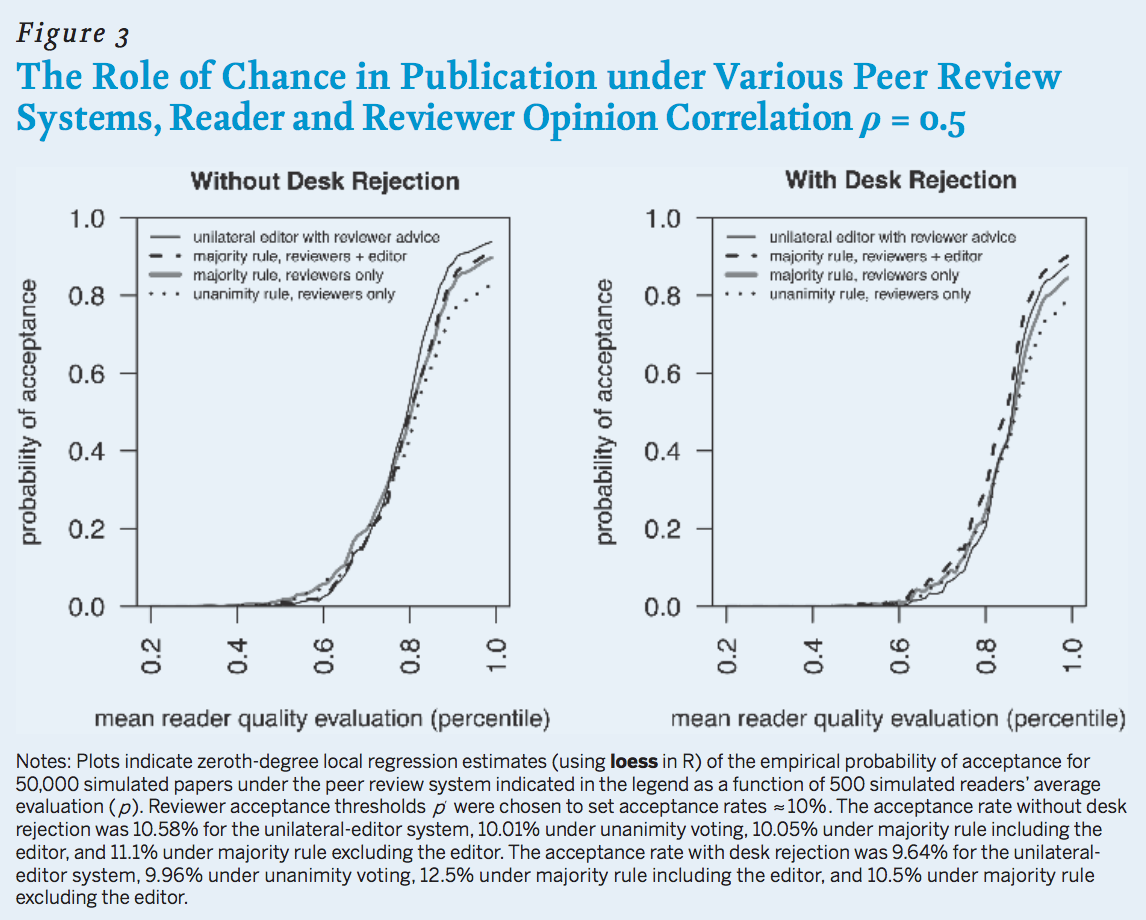

Simulated peer-review systems tended to accept papers that were better (on average) than rejected papers, meaning that peer review remains a filter through which the best papers are most likely to pass.

However, Esarey found that luck still plays a strong role in determining which papers are published under any system. In all systems, the highest-quality papers are the most likely to be published, but a paper that the average reader evaluates as being near the 80th percentage of quality (or 85th percentile in a system with desk rejection) has a chance of being accepted similar to a coin flip.

Esarey also found that journals' readership and review pools affected publication decisions: journals with a more homogenous readership, such as subfield-specific journals, tend to publish more consistently high-quality papers than journals with a heterogeneous readership. Examples of the latter include general-interest journals, some of which are highly ranked.

“When readers and reviewers have heterogeneous standards for scientific importance and quality, as one might expect for a general-interest journal serving an entire discipline like the American Political Science Review or American Journal of Political Science, chance will strongly determine publication outcomes, and even highly selective journals will not necessarily publish the work that its readership perceives to be the best in the field," Esarey says.

However, he adds, “we may expect a system with greater editorial involvement and discretion to publish papers that are better regarded and more consistent compared to other peer-review systems.” In particular, the study found that the system in which editors accept papers based on the quality reports of reviewers -- but not their up-or-down judgment -- after an initial round of desk rejection tends to produce fewer low-quality published papers compared to other systems examined.

"Our finding suggests that reviewers should focus on providing informative, high-quality reports to editors that they can use to make a judgment about final publication (and not focus on their vote to accept or reject the paper)," the paper says. "When a journal does solicit up-or-down recommendations, a reviewer should typically recommend [revision] or acceptance for a substantially greater proportion of papers than the journal’s overall acceptance target in order to actually meet that target."

Beyond process, Esarey says the strong relationship between reader and reviewer heterogeneity and journal quality "suggests that political scientists may want to reconsider their attitudes about the prestige and importance of general-interest journal publications relative to those in topically and/or methodologically specialized journals." While it would be premature to "radically reconsider" judgments about journal prestige and the tenure and promotion decisions they inform, he added, "perhaps one study is enough to begin asking whether our judgments are truly consistent with our scholarly and scientific standards."

While Esarey used his simulation to talk about political science, he told Inside Higher Ed that there's no reason it wouldn't apply to other fields. That is, the analysis itself is "totally agnostic" with respect to discipline, he said. Still, Esarey said that his findings imply that more heterogenous fields without a settled paradigm -- namely political science -- will have a peer review system that is "less efficient that more homogenous fields that do have a settled paradigm, like chemistry."