You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

"Signaling safety" conditions at science field sites.

Robin Nelson, et al.

Many academics regard fieldwork -- the chance to make discoveries and come face-to-face with what they’ve spent years studying -- as a career highlight. Beyond that, it’s a crucial to career development. So a 2014 study highlighting widespread sexual harassment at academic field sites struck a chord -- or rather, was so discordant with many scientists’ perceptions of what fieldwork should be that it’s still frequently cited.

Last week, for example, Science offered the grim finding of that 2014 study as background in a major story on Boston University investigating its chair of Earth and environment for alleged sexual harassment of trainees in Antarctica. Some 71 percent of 512 self-selecting female respondents reported being sexually harassed during fieldwork, the overwhelmingly majority of them trainees at the time, according to the study.

Now the authors of the “Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE): Trainees Report Harassment and Assault,” originally published in PLOS ONE, have more to say. Having recently seen their early findings replicated in two separate studies, one of archaeologists and one of social work students, they’ve published “Signaling Safety: Characterizing Fieldwork Experiences and Their Implications for Career Trajectories” in American Anthropologist. The new paper goes beyond the questions of where and how often harassment occurs in the field to what happens after harassment, and how it can be prevented.

“Signaling Safety” is based on 26 semistructured interviews of original SAFE study participants. Through a qualitative analysis of respondents’ thoughts, two themes emerge: variability in clarity of appropriate professional behavior and rules at field sites, and access, or lack thereof, to professional resources when in the field. Some students’ experiences, including with harassment and assault, ultimately disrupted their careers.

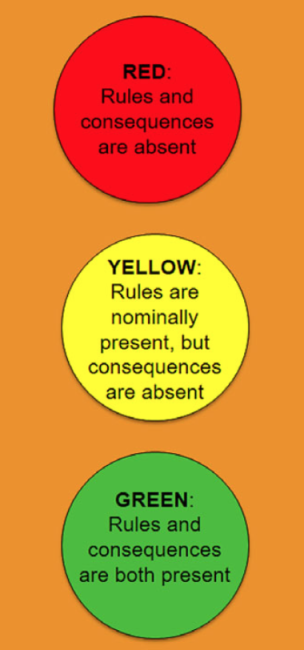

To promote change, the authors propose a “traffic light” construct of red, yellow and green climates to illustrate the field site harassment phenomenon and its consequences. The goal for any field site is to have clearly articulated rules about professional conduct that are actually enforced.

As social and life scientists, “we apply an integrated awareness of the fundamental role of the local physical and cultural environment in individual and community outcomes,” the paper says. “This awareness must also be applied to the way we conduct research. Those workplaces that are tolerant of alienating or harassing behavior, consistent with ‘red’ and ‘yellow’ contexts as described here, silence those targeted, while those with rules, enforcement and leadership, as in ‘green’ contexts, are expected to enhance productivity and innovation.”

Digging Deeper

In interviews, the authors wanted to know how experiences with fieldwork -- good or bad -- shape perspectives on the research climate in the sciences, affect individual motivation and ability to continue in fieldwork-based disciplines, and ultimately impact career trajectories.

The original SAFE study involved 666 respondents. Follow-up interviewees were selected to obtain a diverse group of participants, in terms of experiences (negative field site experiences were overrepresented by design, however). Subjects were mostly anthropologists and archaeologists, and the group was overwhelmingly female. Questions included, “How would you characterize your field experiences?” “Are there any particular incidents, good or bad, that you would like to share?” and “What about the climate at your field site contributed to your experience?” Interviews were then coded based on emergent themes such as alienation, tests, gendered divisions of labor, harassment and assault.

Experiences varied widely. Yet the authors found that field experiences tended to differ in nature -- good or bad -- based on the presence or absence of rules and consequences for any violations of the rules. Clarity over the rules or lack thereof was key: respondents described either a clear understanding of or ambiguity regarding appropriate professional conduct and procedures for recourse, if necessary. Of the 54 field contexts included in the analysis, 36 contexts were described by 21 interviewees as having ambiguous or absent rules. Eighteen field contexts recounted by 12 interviewees were coded as having clear rules or expectations for individual behavior.

Sites described as having clear codes of conduct offered rules, and field directors and researchers had explicit conversations or training sessions to establish site-specific policies. Senior researchers tended to model these desired behaviors and made themselves available for discussion. Consequences for violating these rules also were observed: in one site example, sexual harassment of a peer resulted in the offender being asked to leave the field site.

Sites with ambiguous rules, meanwhile, sounded different. Interviewees described an absence of consequences for breaking rules and an inability to gain clarity on these rules for themselves. Multiple respondents described experiences during which a field site manager systemically harassed the junior researchers at the site.

“I feel like they just see this divide between the field and at home,” said one interviewee, recalling a field site manager. “What happens to you in the field, it’s just like a different world, so the way you behave can -- it’s just completely separated from your daily life.”

Examples of sexual harassment included unwanted flirtation or verbal sexual advances, field site managers insisting on conducting conversations while naked, propositions, and jokes about physical appearance or intelligence that were sexually motivated or gendered, according to the study.

Sexual assault included cases of unwanted physical contact, including physical intimidation, forced kissing, pressing genitalia on the respondent’ s body, attempted rape and rape.

In an interview, the study’s lead author, Robin Nelson, an assistant professor of anthropology at Santa Clara University, said that while reports of assault made headlines in relation to the 2014 paper, the new study sheds additional light on less severe but nevertheless damaging violations of professional conduct.

“There are more hidden kinds of discrimination, such as gender tests and men and women being assigned different kinds of jobs at field sites -- that kind of thing is discrimination, as well, and is quite ubiquitous,” Nelson said. “We’re trying to point out that this is a range or continuum of behaviors.”

Clarity -- and Enforcement -- of Conduct Codes Matter

The authors found a link between rules and behavior, in that sexual harassment was described more often in conjunction with field sites that lacked clarity in rules or standards for behavior.

“The head of the site would systematically prey on women,” one respondent said. “I was in my bed one time and he was with a married master’s student and she was basically just crying and she had to leave the site because he was seducing her and she couldn’t say no … I had to serve as a kind of bodyguard for some of these women and some of them would sleep on the floor because they were afraid he was gonna come into the room at night.”

The director was reportedly undeterred by women leaving the site or hiding. The same respondent said that favoritism for certain men at the site also was present, in ways that advanced their research.

Field site directors at sites with ambiguous or no codes of conduct were also described as not knowing how to deal with reports of harassment or assault. In one instance, in which a trainee was assaulted by a local, the director allegedly said, “In different cultures that’s not abnormal.” The onus of boundary keeping therefore fell on the trainee, who “knew that the attempted rape was outside of the boundaries of appropriate behavior” but was nevertheless “forced to rebuff her attacker’s advances for the duration of the field season,” according to the study.

Access

Access or entree to professional opportunities also came up over and over again. Examples of related, “alienating” behavior include unnecessary tests of physical prowess and gendered divisions of labor. Twenty-four respondents recounted 31 experiences of feeling alienation, stemming from the sense that their expertise or contributions to a field project were underappreciated or devalued.

Gendered divisions of labor were characterized by women and men being tasked with different kinds of responsibilities that “often mapped onto societal prescriptions regarding women’s physical limitations or natural inclinations,” the study says. Such tasks included women being required to do the cooking and shopping in team settings. Again, such behaviors were more often described in contexts where rules were absent than in contexts where they were articulated and enforced.

Tests to establish what the researchers call “in-group/out-group” dynamics also were reported. Those included going on long hikes for nondisclosed periods of time, denying trainees food, water or bathroom breaks during data collection, and sharing pornographic images with a respondent to gauge their reaction.

One respondent described physical tests like this: “We would do these really, really long days but we wouldn’t be warned when they were coming, they would just happen and so I wouldn’t bring enough food … And I would try to vocalize, ‘am tired. I can’t go any further. I need to eat.’ … The second time I spoke up, there were the other two girls who were quick to say, ‘Yeah, we’ve been out a really long time, it’s 8:00 p.m., let’ s go eat.’ We started getting snide comments like, ‘Oh, well, the ladies are hungry so I guess we have to leave.’”

The interviews didn’t by design touch on consequences to one’s career, but such stories emerged anyway. Some respondents described their “productive, enjoyable field experiences as reasons to pursue academic work,” according to the study. But many recalled instances in the field being the beginning of persistent problems. Several respondents described having to endure repeated encounters with those who had made their field environments hostile, even after leaving the site. Some decided to alter their career paths. One respondent said her adviser forbade her from urinating while conducting fieldwork, criticized her weight and took food from her, questioned her intellect and threw objects while angry. She tried unsuccessfully to report the abuse back at her home institution but had no recourse other than to leave the department. The professor in question, meanwhile, received three new advisees.

Egalitarian Behaviors and Enforcement

Positive experiences in the field enhanced the career, research and leadership trajectories of respondents. Many respondents described positive field experiences that intensified their interest in their research. And notably, respondents who stayed in the academic pipeline despite negative experiences described adopting procedures and paradigms to improve their fieldwork climates for their trainees and junior collaborators.

Twelve of the 26 interviewees who reported positive field contexts described sites that were fair or egalitarian in execution, living and working conditions that were intentional and safe, and directors who anticipated problems and outlined reporting lines and had time for conversations. Having women in leadership roles at these sites also was important.

Nearly everyone with positive experiences also described having all scientists’ perspectives valued. One former trainee respondent said, for example, “I was treated the same as people with Ph.D.s … with the same consideration as people with Ph.D.s and asked for input and not talked down to.”

“Conscientious field site directors explicitly established the culture of the site,” the paper says. “Among favorable contexts, explicit anticipation of potential problems appears to be a successful strategy to prevent problems or ameliorate conflict.” One respondent compared laying out ground rules to “having the sex talk with your kids” in terms of awkwardness, but also in necessity.

“I think it’s worth getting it out of the way and having an honest conversation, and I think it makes for a better experience overall for both the people who are running those field programs but also the people that are a part of the team,” the respondent continued.

Leading the Way to Reform

“Signaling Safety” says that leaders, including principal investigators of major field sites and those in positions of power in professional societies, can effect culture change “by prioritizing equal opportunity and inclusion as explicit values for the field sciences.”

Nelson said that since publishing the first manuscript in 2014, she and her co-authors have been talking to researchers who are actively working to change the culture at their field sites, and communicated with professional organizations “that are tuning in to the effects of gendered discrimination,” considering best practices for the promotion of more equitable professional spaces.

“While we are optimistic because there is a larger discussion occurring regarding gendered discrimination in academia,” she added, “we recognize that there is much work to be done particularly at the intersections of race, ability, sexuality, gender identity and class.”

Ed Liebow, executive director of the American Anthropological Association, said the group remains committed to a “zero-tolerance policy regarding sexual harassment and behaviors that contribute to a hostile work climate.” Enforcement is notoriously tough for professional societies, who can’t, say, suspend a professor from work for misconduct. Further, the anthropological association doesn’t accredit field schools. But Liebow said that his association, through a variety of means, and consistent with its Statement of Professional Responsibilities, is increasing member awareness of responsibilities to intervene as observers or bystanders, and awareness of resources available to victims of unwanted behaviors.

Of the new paper, Liebow highlighted the finding that rules and consequences reduce the incidence of professional misconduct.

Nelson said she didn’t necessarily think that abuse is worse at field sites than it is in other academic contexts, but that physical isolation and variety of other factors make field sites ripe for misconduct where rules aren’t articulated and enforced. Moreover, she said, fieldwork is so important to young scientists’ careers that “walking away” is as hard professionally as it can be logistically.

Jane Willenbring, a professor of geology at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, is among the women who recently reported the Boston professor, David Marchant, for alleged misconduct. She waited more than a decade to tell the university that he had pelted her with rocks while she was urinating the field, blew volcanic ash into her eyes on purpose, repeatedly called her names and pushed her to have sex with his brother during a trip to Antarctica, she said, because her fear of professional retaliation was so great. (Marchant has not publicly commented on the accusations, other than to say he is cooperating fully with the university's investigation; Science reported that some documents related to the case suggest Marchant has denied the allegations.)

Willenbring has said she switched her research to the Arctic as a direct result of working with Marchant in Antarctica. As to what contributes to misconduct in the field, Willenbring said she thought there’s a certain “what happens in the field stays in the field” mentality.

Many times, however, she said, “there also aren’t means of communication so you feel so isolated and there are only the voices of the perpetrators to listen to.” When a victim returns home, she said, it might seem easiest to “move on,” fueled by a sense of futility and fear of retribution.

Faculty members “very rarely get fired,” she added via email. “Institutions just 'pass the trash' to another university, and then the victims wonder what the point of it all was. The complainants ended up just being part of a faculty member’s move -- probably with a raise at the new institution -- to abuse students at a new place and likely take a hit to their own reputation."