You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Photo by Caroline Brehman/CQ-Roll Call, Inc. via Getty Images

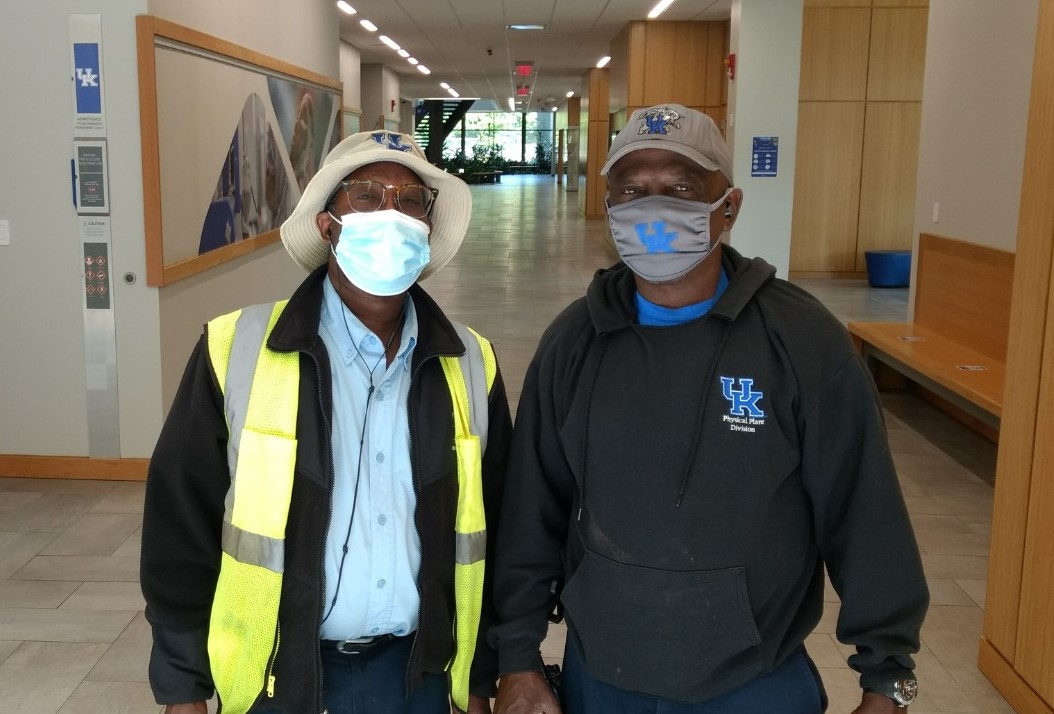

Donald Moore has worked as a custodian at the University of Kentucky for nearly two decades. He likes the job and his coworkers.

“I love being there, servicing students,” he said. “Being of service to somebody else is the main focus of being there.”

But after 19 years, Moore still makes less than $15 an hour. He is 57.

More than 400 miles away, in Columbia, Mo., the situation isn’t much better for employees. In 2018 the state voted to raise the minimum wage to $12 an hour by 2023. But because of legal technicalities, the University of Missouri at Columbia wasn’t legally obligated to pay that new minimum. So the administration said it wouldn’t.

That meant in 2019, some workers who cleaned the floors, served the food and cut the grass at Mizzou were making as little as $9.70 per hour. Dining hall workers were using the university food pantry to feed themselves.

Nonacademic, nonadministrative staff members often are left out of conversations about higher education, race relations and campus climate. But these university workers are the wheels upon which a college runs. They are -- in nearly every sense of the word and on every kind of campus -- essential. They also tend to be poorly paid, underappreciated and disempowered. They are the first to be laid off and the last to be celebrated. At many, many institutions, a majority of these workers are people of color. At some, like Mizzou and Kentucky, the majority are Black.

Often, these low-wage workers more accurately reflect the demographics of a college town than the students who attend it.

“If you look and see who’s treated badly and who’s treated well, you don’t have to look that hard,” said Anthony Paul Farley, a professor of law at Albany Law School. “Which group has the most Black people in it -- that’s the one that’s going to be given the narrowest range of choices.”

A Precarious Workforce

The relationship between U.S. colleges and universities and their workers didn’t always look this way. Competition, changes in how universities are run and managed, and widespread outsourcing all contributed to shifts in worker treatment and compensation.

In the 1980s college enrollment dipped nationally, and competition between colleges intensified. Administrations searched for ways to cut costs and eke out any advantage. Outsourcing jobs was one way to help get there.

Dining services were among the most obvious areas to contract out to a vendor. Large private companies already were responsible for the food in hotels and prisons, and student expectations about college food were getting more demanding. Vendors would also build in incentives, such as payment for a new dining hall, in return for long-term contracts with a college.

Today about half of colleges, mostly large ones, contract out dining services, said Kevin McClure, a professor of higher education at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Colleges also have turned to paying vendors to run other services, such as parking lot management and custodial work.

At public institutions, that essentially means privatizing a state-run workforce, which often results in lower compensation, benefits and workplace protections for staff. Those workers also stand to lose certain benefits, such as tuition remittance, as a result.

“[Before contracting] you could work a basic maintenance job or other low-wage work that is nevertheless stable and tied you to a community at your institution,” said Tom DePaola, a research assistant at the University of Southern California who studies labor trends in higher education. “These were institutions that were educating the next generation and finding all of our new medical and scientific innovations. Workers were proud to be a part of that even in some nonacademic way.”

A serious backlash to outsourcing occurred on college campuses, most notably in the 1990s as part of the Justice for Janitors campaign by the Service Employees International Union. But while those protests and campaigns notched some significant wins, they were largely unsuccessful at preventing outsourcing.

“Now you have a huge population of deeply alienated workers who are increasingly agitated and fearful,” DePaola said. “By and large, these workforces are provided by third-party contractors at very steep discounts. Those companies are just managing their own at-will labor forces in ways that are designed largely to guarantee that these people don’t get benefits and don’t have any security. Colleges don’t have to worry about who’s doing the work as long as there’s always a ready supply of workers.”

One of the major things that makes contracting services attractive for universities, said McClure, is that the administration then no longer has any financial responsibility to those workers, leaving decisions about workers' livelihoods in other's hands.

The pandemic made this lack of accountability more apparent than ever as outside vendors and contractors shed employees as the economic fallout of the crisis grew. Students on some campuses were so concerned about the livelihoods of these low wage workers that they called on college administrations to continue to pay workers furloughed or laid off by the contractors.

“These workers that are here on a campus every day of the week, working long hours, building relationships with students, in a moment of crisis learn very quickly that they, in the eyes of the university administration, are not part of the campus community, but are rather employees of this other company,” McClure said. “The reality is that in many ways, the entire purpose of contracting out was that the university would not be financially responsible for those people.”

Outsourcing was only one change that has occurred in recent years in higher education, and it is not widespread for every job role. Custodians, for example, are less likely than dining workers to be contractors. Janitors at Mizzou and Kentucky are directly employed by the universities.

But amid the shifts that have affected employee compensation and status, college and university presidents and other executive officers are earning more. At the University of California system, for example, from 2005 to 2015, the average salary of the top 1 percent of employees grew from seven to nine times that of the median full-time employee.

At the end of that ten-year period, the top 10 percent of system employees -- likely executives, coaches and chancellors -- accounted for over 30 percent of total payroll costs. The bottom half of employees, representing five times as many people, only accounted for 22 percent.

While the disparities in compensation between those at the top of the pay scale and those at the bottom are stark at many colleges and universities, administrators at the University of Kentucky say they’ve worked to protect the jobs and salaries of their hourly workers despite the budget deficit caused by the pandemic.

Jay Blanton, the university spokesman noted that even with a $70 million shortfall, Eli Capilouto, the president of the institution, remained committed to a salary increase for workers in July that raised the starting wage to $12.50 an hour from $10.40.

“I would submit that we have driven our local market in wages in recent years, perhaps not surprisingly as the largest employer,” Blanton said in an email. “But President Capilouto, nevertheless, made a conscious and intentional choice on wages because he thought it was important to lead in our region and state. And he stuck with that decision, even in the face of a significant budget gap that had to be closed ... [and] we closed the gap without layoffs, another commitment we made to our employees.”

Culture of Disrespect

Beyond pay and benefits, many Black workers on college campuses say they want dignity in their work and to be treated with respect by their institutions. Many of the workers Inside Higher Ed spoke with for this article were wary of naming race as a factor in their poor treatment. They said they saw their situations more as a struggle between bosses and working people.

At Mizzou, custodians waged their own fight against outsourcing this year, when the administration announced it was considering terminating its custodial department and hiring a third-party vendor.

After mounting opposition to the plan by a coalition organized by Missouri Jobs with Justice -- that included the campus custodial workers' union, the Missouri Democratic Socialists of America and the Mid-Missouri John Brown Gun Club -- the administration relented.. It would make cuts elsewhere.

But before acquiescing, the university took 70 days to make a decision. Tyrone Turner, a carpenter at Mizzou for 28 years, said several custodians couldn’t stand the insecurity. They ended up leaving their jobs before a decision was made.

“You’re not talking about someone that makes $100,000 a year; you’re talking about someone who’s working two jobs, working paycheck to paycheck to make ends meet,” Turner said. “They should have had a decision made whether they were going to do it or not. But to leave people on hold for months, to leave it up in the air for that long, is almost cruel. It’s almost injust.”

Turner said he doesn’t fault the university for looking to save money. Budget cuts have been the biggest issue for Mizzou workers in recent years, he said. When Turner arrived at the university in 1992, his department had 75 employees. In the past five years, that number has been cut to 25. The administration is constantly looking for ways to do more with less. (The state of Missouri experienced a 14 percent growth in public college enrollment since 2008 even as state funding declined by 26 percent during that same period.)

Turner said a majority of custodians at Mizzou are Black and Latino. "With all the injustice things we’re talking about in the country today, they want to pick on those people. They’re the lowest paid, the blackest and the brownest. What kind of message is that sending to the whole community? That we don’t give a shit about those people?” he said. “They wouldn’t do the president that way. They wouldn’t do a coach that way.”

Many campus workers say they love their jobs. A university can be a home. Coworkers can be a family. But often that positive experience comes despite a relationship with an administration, not because of it.

At Kentucky, Moore, the custodian, describes a culture of favoritism and disrespect. Janitors come in every morning to clean through the summer heat, but in some buildings, the air-conditioning isn’t turned on until administrators arrive.

Some of his coworkers are Congolese refugees. They are particularly belittled and talked down to by supervisors, he said.

But Moore said he’s not sure how race plays into it. His white coworkers don’t escape poor treatment, he said.

“We’re custodians,” he said. “We get more respect from faculty and staff and students than we get from our administration.”

Blanton said the administration has not been made aware of any disrespectful treatment of employees, Congolese or otherwise, by supervisors. In regards to the air-conditioning not being turned on for custodians, Blaton said via email, “As part of our energy conservation program, when buildings are unoccupied the air temperature settings are changed. As the pandemic began and many of our non-health care employees worked remotely, that left many buildings with low or no occupancy, and some settings were changed. However, if and when concerns were raised, building temperature settings were addressed on an individual building basis.”

In an annual survey conducted by the consulting firm ModernThink, the University of Kentucky has been named a Great College to Work For the past three years, appearing on the “honor roll” in 2020. In an internal survey of over 4,000 staff members, 90 percent of respondents said their supervisor, director or chair treats them with respect, and 70 percent said employees are treated with respect regardless of their position. It is unclear how different departments and roles were represented among respondents.

“We deeply respect and appreciate all of our custodial staff,” Blanton wrote.

‘We Deserve It’

The COVID-19 pandemic -- and universities’ response to it -- has been an inflection point for some workers.

“I’m on pins and needles,” Pierre Smith, a groundskeeper who has been working for the University of Kentucky for 15 years, said in August. At the time, 25,000 students had just moved back onto campus after leaving in the spring. The university has since had nearly 2,300 student cases of COVID-19. More than 100 employees have been infected.

Smith is 54, and his girlfriend uses a breathing machine. He said he doesn’t want to think about what would happen if he brought the virus home.

Smith is 54, and his girlfriend uses a breathing machine. He said he doesn’t want to think about what would happen if he brought the virus home.

Groundskeepers and custodians at Kentucky will not be given hazard pay for working this semester. And before it was raised by the workers’ union (which does not have the power to bargain with the university), the administration wasn’t planning to offer any testing to staff. The union also is pushing the university to cover any health-care costs associated with COVID-19 for campus workers.

Farley, the law professor at Albany Law School, has argued that universities should stay remote to protect the health of their workers of color.

“What experts are certain about is that reopening campuses will reproduce and reinforce existing racial disparities. Workers of color bear an uneven risk of hospitalization and death,” Farley and his four co-authors argued in Bloomberg Law. “People of color are also more likely to be the essential workers in the university setting who are exposed to more risk -- those who clean university spaces, who interact with students as support staff, the facilities managers, adjuncts and food service employees.”

The image universities present to students, faculty, donors and the public is one where knowledge is pursued for knowledge’s sake, Farley said, and barriers between cultures, generations and nations are broken down.

“That implies a kind of humanism that we are not exhibiting when we tell the workers, ‘Show up, get sick and that's your problem,’” he said. “Blithe disregard for the health of the workers undermines the whole mission of the university.”

Jeff Waddell, a union steward who has worked as a cleaner at the University of Pittsburgh for five years, cited ongoing anxiety among campus workers. Pitt has brought 19,000 students back to campus, and since Waddell spoke with Inside Higher Ed in August, the university has seen 314 total positive COVID-19 cases.

"The only way that we beat back is when workers, Black and brown workers, but all workers, organize against the legacies that these institutions subconsciously and consciously try to perpetrate."

-- Josh Armstead

The administration has given out masks sporadically, he said in August. And although students have access to free tests, employees are asked to go to their own doctors for a diagnosis. Waddell himself is worried because he’s over 60 and thus at increased risk of complications from COVID-19.

“We need hazard pay. We need additional sick time off,” he said. “Our life is on the line daily.”

The university offered an additional 10 days' paid sick time to staff in March, Waddell said. But many workers have had to use that time to care for sick relatives or watch children when childcare became unavailable.

“We’ve proven we deserve it. Every time they’ve asked us to step up, we have,” he said. “A pat on the back doesn’t pay your bills.”

As at many institutions, most cleaners at Pitt are people of color. But Waddell doesn’t feel that’s part of overt racism on the university’s part.

“Who applies for cleaners’ jobs right now?” he said. “There’s a lot of Black and brown people that need jobs.”

Josh Armstead, vice president of UNITE HERE Local 23, who works in the dining hall at Georgetown University, said he sees the racial stratification of labor at Georgetown as part of a larger systemic problem.

“It’s an institutional problem when it comes to the value of Black and brown bodies,” he said. “For many, many hundreds of years in this country and on this continent, Black people and brown people were subjected to the servile jobs of cooking and cleaning and other types of work that would sustain the upper class.”

Armstead works for Aramark, the contractor for Georgetown’s dining halls. In the spring, when Aramark furloughed dining hall and food service workers, the university paid employees the wages they would have earned. Armstead was able to tell his supervisors he wouldn’t be coming in this semester because of his young son, a privilege he said he owes to his union.

“The only way that we beat back is when workers, Black and brown workers, but all workers, organize against the legacies that these institutions subconsciously and consciously try to perpetrate,” he said. “And capitalists that want the lowest amount possible to pay for the highest extraction of our labor.”

Race and Labor

Like Armstead, many of the Black workers interviewed said they’ve found power in the labor movement and the unions that represent them. Some said that without a union, they doubted their employers would negotiate with them at all.

Armstead said his experiences at the negotiating table with Aramark were a turning point in his understanding of power.

“[The negotiator] looks at all of us and he said, ‘We are a $14 billion company and we will not be intimidated by our workers,’” he recalled of an interaction in 2015. “Who’s the intimidator? The $14 billion corporation that currently controls my employment? Or the folks who are fighting for a better day?”

(Aramark did not respond to a request to comment.)

Philosophers and political scientists have developed numerous and competing ways to think about race, class and labor in America.

Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, a philosophy professor at Georgetown whose work is influenced by Black radical tradition, said his personal view on racial stratification aligns with a concept called “racial capitalism,” first defined by political philosopher Cedric Robinson.

Táíwò said racial stratification means people are invested in maintaining or advancing their own status in a racial hierarchy, which keeps them from attacking a broader system of capitalist inequality.

“Race is a technology for keeping people invested in antagonistic relationships that keep the current system going,” he said. “People fight each other for places on the hierarchy rather than the system itself.”

Through that lens, the overrepresentation of people of color within the low-wage university workforce is unsurprising. The solution, Táíwò argues, is political organizations that align the interests of the people at the bottom who may differ by race. One such example is unions.

Of course, the American labor movement itself has had its own history of racism and xenophobia.

“It’s not magic,” Táíwò said. “It doesn’t erase bigotry.”

Several labor unions that exist today excluded Black workers until the 1960s.

“In the history of unions, there’s certainly been what we might call a race problem, and there’s a complicated history around that that stems from racial exclusion,” said Keona Ervin, a professor of history at Mizzou who studies Black women and the labor movement. But today, Black Americans are more likely than any other racial or ethnic group to be union members.

“Black workers have been indispensable to advancing worker rights struggles in the United States, in part because of just their status in the labor economy and the economy more generally. Often they have been relegated to the lowest-paying positions, low-wage labor, what might be classified as undesirable labor. And from that vantage point, they’ve really had a clear-eyed take on what economic exploitation looks like in the workforce,” she said.

“What’s interesting today is you are seeing many more traditional union organizations embracing a platform that recognizes the need to build racial justice into a movement that seeks to build worker power.”

Black workers, she said, have a historical tradition of seeing unionism as a vehicle for an expansive vision of social justice that includes issues like antiracism, antisexism, health care and childcare. Armstead himself said he sees universal health care as the next fight for workers to win.

A Changing Campus

Racial justice is at the center of campus debates and activism and yet lower-wage workers often are left out of those conversations.

“The kinds of struggles that happen on university campuses tend toward the symbolic,” said Táíwò. “They also tend to emphasize to an outsize degree the kinds of concerns that academic workers have as academics rather than as workers, and that students have.”

Weightier decisions from a university, such as whom it employs and how it interacts with its surrounding city or town, could be taken more seriously, he said.

“I don’t see much point in decolonizing a reading list on a campus that is forcing Black people out of their homes,” Táíwò said. “I don’t even think hiring Black faculty to give more radical discussions at fancy conference centers and ignoring the people who clean up after them is a politics that makes sense, of racial justice or of any other sort.”

For people who want to change how universities operate and treat their employees, much attention is often paid to the role of tenured faculty members. Professors with secure job protections often don’t do enough to advocate for their disempowered colleagues, some say.

“Academic workers got comfortable with the idea that we had formal protections around things and that took a lot of the pressure off the need to build and maintain networks of power that could be leveraged against administrative austerity or overreach,” DePaola said. “Faculty were losing their power, and rather than sort of confront that in the '70s and '80s and '90s, instead they just sort of dug deeper into their bubble of privilege.”

But in a few cases, the COVID-19 crisis has kicked off increased solidarity between campus workers and their peers in academia. “Wall-to-wall” unions and staff-faculty coalitions have sprung up at several institutions.

"I don’t even think hiring Black faculty to give more radical discussions at fancy conference centers and ignoring the people who clean up after them is a politics that makes sense, of racial justice or of any other sort."

-- Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò

At Rutgers University, for example, several different unions formed a coalition to try to bargain with the university together. Todd Wolfson, the president of the faculty union there, said it was important to try to use the prestige and power of the full-time faculty to protect and bargain for more vulnerable staff.

“Faculty, me and my unit, we have felt special within the university environment and maybe even treated as special,” he said. “We’re not special -- we’re workers like everybody else.”

Some in higher education have rebuffed moral arguments that universities should provide more for their workers. A university, they say, is like any business, a firm serving customers, and is under no ethical or legal obligations to its staff. Indeed some have argued that the ethical thing for university administrations to do is dismiss calls to pay their furloughed staff and invest that money to ensure the longevity of the institution.

Wolfson said moral arguments can only get workers so far.

“They will not accept the moral argument. You want to make a moral argument to the governor, to the Legislature, to the New Jersey public, and we do,” he said. “But if we really want to win, we have to organize. This is all about power.”

Today, thousands of college students and hundreds of college employees have been infected with the coronavirus. This month, LeeRoy Rogers, a custodian at Drury University in Missouri, died of COVID-19 after coming in to work. Hundreds of others have been furloughed or fired. Employees continue to sweep floors, prune trees and take out the trash for institutions they love.

The days continue. The work goes on.

This article was updated to include a comment from the University of Kentucky about employee compensation.