You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

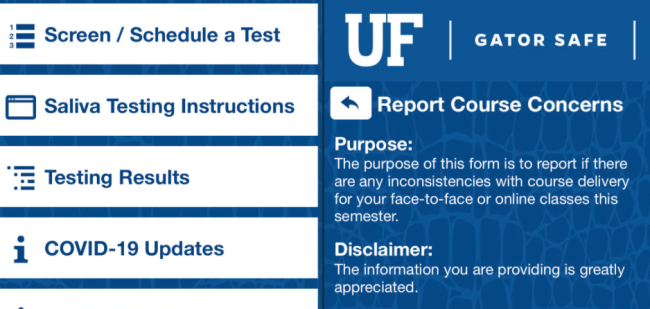

GatorSafe app

University of Florida

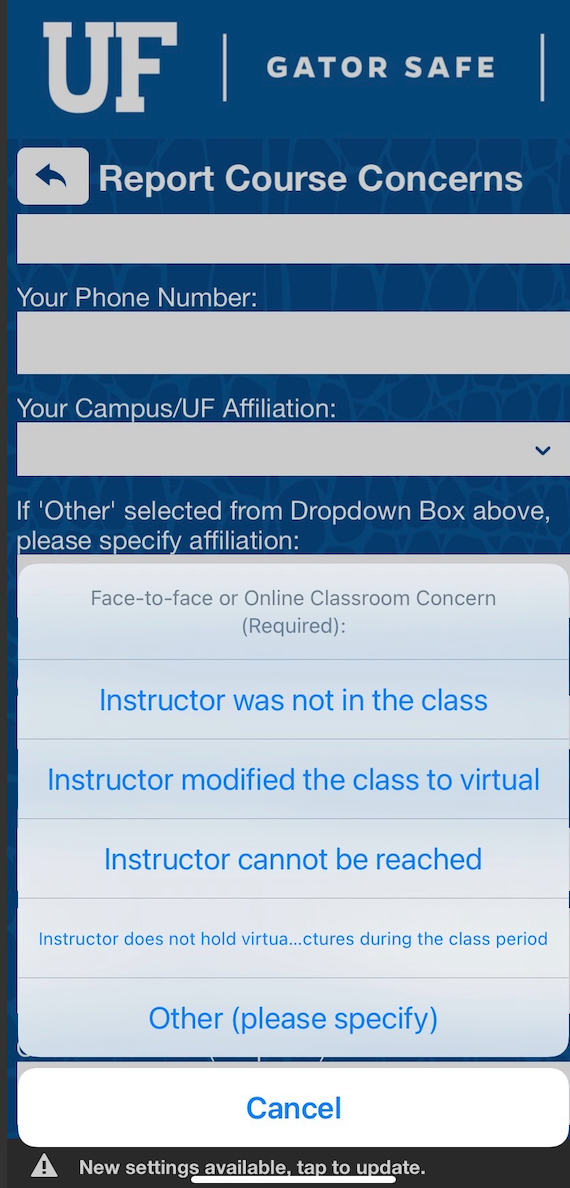

Instructor was not in the class.

Instructor modified the class to virtual.

Instructor cannot be reached.

Instructor does not hold virtual lectures during the class period.

The University of Florida has updated these course concern-reporting categories since they debuted on its GatorSafe app earlier this month. But some professors still think of the app’s new function as a “tattle button” designed to catch professors who don’t want to teach in person.

“Demoralizing. It’s insulting. I think it’s a real statement about how they feel about us as professionals, that they don’t trust us to think seriously about how to deliver our courses,” said Susan Hegeman, professor of English and a spokesperson for the campus’s United Faculty of Florida union chapter. “They need to check up on us.”

Many institutions experienced clashes between administrators and faculty members over whether or how to proceed with in-person instruction throughout the pandemic. Tensions at Florida have been particularly high, with the university pushing for as many in-person courses this spring as were scheduled in spring 2020, prior to the coronavirus shutdown. University officials say half of the 50,000 students enrolled signed up for at least one in-person course this term, and administrators want professors in the classroom teaching in the HyFlex model, with some socially distanced students in the classroom and others following synchronously online, to accommodate them.

Some professors object to the university’s embrace of HyFlex instruction as an inappropriate, one-size-fits-all solution to a complex problem. The union, for instance, says discussion sections are difficult to teach with part of the class in person and the rest online. Foreign languages are also difficult to teach in masks, members says.

Beyond pedagogical issues, some professors and graduate students report that they either had to jump through administrative hoops to get a medical waiver to teach remotely or that they were denied one.

Amid these discussions, rumors began to fly around campus about professors possibly teaching their in-person courses remotely instead. The university responded to this chatter, and other concerns about the student experience, by adding a function to the pre-existing GatorSafe public safety app for students to log their concerns about spring courses.

Under the app’s initial function for reporting concerns this term, students were prompted to choose from dropdown menu options, including “Instructor modified class to virtual.”

Under the app’s initial function for reporting concerns this term, students were prompted to choose from dropdown menu options, including “Instructor modified class to virtual.”

"If there are any inconsistencies with course delivery for your face-to-face or online courses, such as not being provided the opportunity to meet in person for your face-to-face class, you can use the GatorSafe app to report concerns," D'Andra Mull, vice president for student affairs, wrote to students in a Jan. 11 memo. "UF staff will review every concern and follow up as appropriate."

The faculty was not pleased, with some professors saying that this kind of surveillance and undermining of their professional expertise would push them over the edge into resigning, or crying.

Paul Ortiz, president of the faculty union and director of Florida’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, told The Gainesville Sun that the function “smacks of McCarthyism.”

"We work hard to do our jobs," Ortiz said. "And then we have a university that's treating us as if we're morons. That's why a lot of people are upset."

Last weekend, in response to some of the negative feedback, Florida amended the function so that students would have to write in their concerns, without having ready-made suggestions about what their professors had done wrong.

Steve Orlando, university spokesperson, said the university had received 12 legitimate reports through the function thus far, including two reports that professors teaching in person were not wearing their masks properly or at all. No report involved a professor teaching remotely instead of in-person.

Regarding the change, Orlando said that deans offered faculty feedback about the original function to the provost, and the administration ultimately decided it would be more comfortable “with it simply being an open-ended question.”

“As long as students still have the ability to let the university know of concerns that they have, that’s the key thing,” Orlando added.

Regarding outstanding concerns about in-person teaching, Orlando said the university did make exemptions based on medical necessity. He said the request for in-person instruction by some 25,000 students is proof of the demand for such instruction.

Hegeman got a medical waiver to reach remotely after appealing an initial rejection, she said. She did not share her condition but said it should have been a “no-brainer” and that too many of her colleagues who are over 60, suffering from asthma or are cancer survivors are being forced to return to the classroom prior to being vaccinated.

The changes to the reporting function don’t help those colleagues or anyone else who feels professionally affronted by the very concept, she said.

“They should give us the professional courtesy of letting us determine how to best teach our courses under difficult circumstances,” Hegeman said, adding that she’s not sure if students really are aching to return to the classroom while the coronavirus is still raging. “And [the university] should have been more flexible about the medical accommodations for sure.”