You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

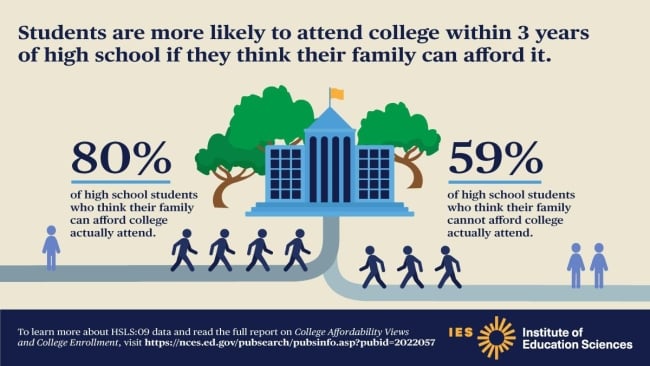

Courtesy of the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics

In 2012, when most students in a new study were juniors in high school, researchers asked them whether they agreed with the following statement: “Even if you get accepted to college, your family cannot afford to send you.”

Nearly a third of the students—32 percent—agreed or strongly agreed with that statement.

Three years after high school, 59 percent of this group—“the non-afforders”—had ever attended college, compared to 80 percent of their peers, “the afforders,” for whom perceived affordability was not an issue.

The study results are presented in a new analysis, “College Affordability Views and College Enrollment,” being published today by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics.

“College affordability is a major concern for families, and paying for college looms large for students, particularly students who would be the first in their families to earn a degree,” NCES commissioner Peggy G. Carr said in a written statement. “This new analysis reveals that students are more likely to enroll in college if they believe their family can afford to send them. A student’s belief in their ability to afford college may have important implications for how they search for information on paying for college while in high school or whether to apply.”

The study also looked at the relationship between perceptions of affordability, parental education level and college enrollment.

The group most likely to enroll in college were students who believed they could afford college and had at least one parent with a bachelor’s or other college degree. Ninety percent of those students had ever attended college within the first three years after high school.

The group least likely to enroll in college were students who believed they could not afford college and had at least one parent with a high school diploma or less. Just 55 percent of those students had ever attended college within the first three years after high school.

Across all levels of parental education, students who perceived college to be affordable when they were high school juniors were more likely to have ever enrolled in college within three years of high school than their peers who did not, as shown on the chart below.

Sandy Baum, a nonresident senior fellow at the Urban Institute, a think tank focused on socioeconomic mobility and equity, said that in evaluating the NCES study, it would be useful to know to what degree the students’ perceptions of their inability to afford higher education correlated with their actual family circumstances. Without that, she said, “We don’t know if whether what we found out is whether it's perceptions that matter or whether it’s actual circumstances that matter.”

Baum, who studies college finance and affordability, said she was heartened nonetheless by the fact that even among students who felt they couldn’t afford college, and who came from family backgrounds where a parent did not go to college, more than half still enrolled.

“That’s encouraging to the extent that it means that somehow it’s possible to overcome those circumstances,” Baum said. “Maybe later they learned about financial aid. Maybe they learned it’s not as expensive as they thought. You can be very discouraged by the gap between the different groups, but it’s not at all surprising there’s such a gap. I think it’s pretty encouraging so many go to college. That means we should be able to raise that number.”

Terri Taylor, strategy director for innovation and discovery at the Lumina Foundation, which focuses on expanding access to higher education and other post–high school learning opportunities, said one thing the study makes clear is how early students start to develop ideas about the affordability of higher education.

“It’s not necessarily if their family could actually afford it—it’s if they thought they could, and it’s if they thought they could when they were a junior in high school,” Taylor said. “It just shows that perceptions of all of this are formed earlier than when students are filling out a FAFSA [Free Application for Federal Student Aid]. A lot of financial aid information happens senior year, but I think what this study shows is perceptions are there earlier. And if you know anything about human behavior, you know perception matters with the steps that you take later.”

Joni E. Finney, a professor of practice at the University of Pennsylvania and director of the Institute for Research on Higher Education, said it’s not just a matter of perception. “I don’t think we have a messaging problem,” she said. “We have a real cost problem on our hands.”

A report Finney co-authored in 2016, “College Affordability Diagnosis,” found that across states with high proportions of families earning less than $30,000 annually, low-income families would, on average, be required to spend between 28 and 47 percent of annual family income for a member of the family to attend a public two-year college, between 41 and 73 percent of annual family income to attend a public four-year nondoctoral institution, and between 39 and 89 percent to attend a public research university.

The report also found that for families making $30,000 or less, basic living expenditures exceed family income.

“For these families the high cost of college is not a perception but a reality that they must deal with,” Finney said.