You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

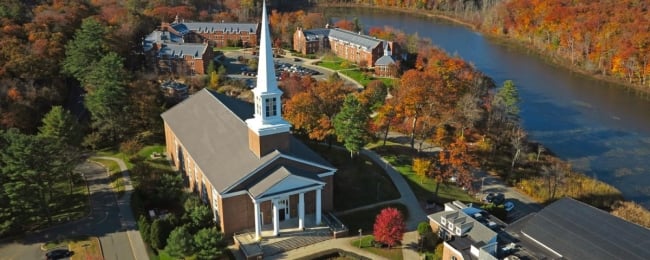

Gordon College

The Supreme Court rejected an appeal Monday by Gordon College of a ruling by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court that its professors who do not teach religion or religious texts are not covered by the “ministerial exception.”

The exception allows religious colleges to be free of governmental scrutiny in how clergy or professors teach religion.

Gordon, a Christian college in Massachusetts, believes it should be protected by the exception from a lawsuit by Margaret DeWeese-Boyd, who teaches social work at Gordon, and who accused the college of discriminating against her when she applied to be a full professor for her support of gay rights.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in March found that Gordon did not deserve to be free of a suit by DeWeese-Boyd because of the ministerial exception.

“Her duties as an associate professor of social work differ significantly from cases where the ministerial exception has been applied, as she did not teach religion or religious texts, lead her students in prayer, take students to chapel services or other religious services, deliver sermons at chapel services, or select liturgy, all of which have been important, albeit not dispositive, factors in the Supreme Court’s functional analysis,” the Massachusetts court ruled.

The court ordered more hearings on the suit. But Gordon appealed the issue of the exemption to the Supreme Court.

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the appeal. Normally such rejections are not accompanied by statements from the justices. But in this case, four conservative justices signed an opinion on the case by Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. questioning the Massachusetts court’s ruling. The other justices who signed are Amy Coney Barrett, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas.

“Although the state court’s understanding of religious education is troubling, I concur in the denial of the petition for a writ of certiorari because the preliminary posture of the litigation would complicate our review. But in an appropriate future case, this Court may be required to resolve this important question of religious liberty,” Justice Alito wrote.

He noted that all faculty members at Gordon are required “to sign a ‘Christian Statement of Faith,’ which affirms that the ‘66 canonical books of the Bible as originally written were inspired of God’ and that there ‘is one God, the Creator and Preserver of all things, infinite in being and perfection.’”

DeWeese-Boyd signed the statement, and she noted in her application to become a full professor that student evaluations said she “did a great job of connecting class materials with Christian faith” and “calling our thoughts to a higher level of Christian responsibility.”

The college denied her request, citing a lack of scholarly productivity. She sued, arguing the real factor was “her vocal opposition to [the college’s] policies and practices regarding individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer.”

The college allows such students and professors to study and teach at Gordon but requires them to follow the college’s code of conduct, which says, “Those words and actions which are expressly forbidden in Scripture, including but not limited to blasphemy, profanity, dishonesty, theft, drunkenness, sexual relations outside marriage, and homosexual practice, will not be tolerated in the lives of Gordon community members, either on or off campus.”

Justice Alito wrote, “The state court asserted that this [teaching] responsibility was ‘different in kind’ from the kind of religious education” in previous Supreme Court’s decisions. “That conclusion reflects a troubling and narrow view of religious education. What many faiths conceive of as ‘religious education’ includes much more than instruction in explicitly religious doctrine or theology. As one amicus supporting the college explains, many religious schools ask their teachers to ‘show students how to view the world through a faith-based lens,’ even when teaching nominally secular subjects.” He added, “An English professor at a secular college might see nihilism and skepticism in Shakespeare’s King Lear, while a professor at a Catholic school might present it as a pilgrimage to redemption.”

Alito noted that if Gordon loses the case in state court, there is nothing to prevent the Supreme Court from hearing it again.

It takes only four justices to agree to hear a case, so Gordon would seem to be assured a hearing at the Supreme Court if it loses in state court. (The other justices did not comment on their rationales for rejecting the Gordon appeal.)

DeWeese-Boyd could not be reached for comment.

Rachel Laser, president and CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, said, “Professor DeWeese-Boyd’s case highlights an alarming trend: religious employers are urging courts to adopt an ever-broader interpretation of the ministerial exception. They want it applied not just to clergy and some private school educators with significant religious duties, but to all employees at religious organizations. The ministerial exception was meant to ensure that houses of worship could freely choose their clergy; it was never intended to be a free pass for any religious employer to discriminate against its entire workforce and sidestep civil rights laws.”