You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Fans cheer on the Alabama Crimson Tide at a home game against Louisiana State University in 2019. “Yea Alabama!” is played any time the Crimson Tide scores.

Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

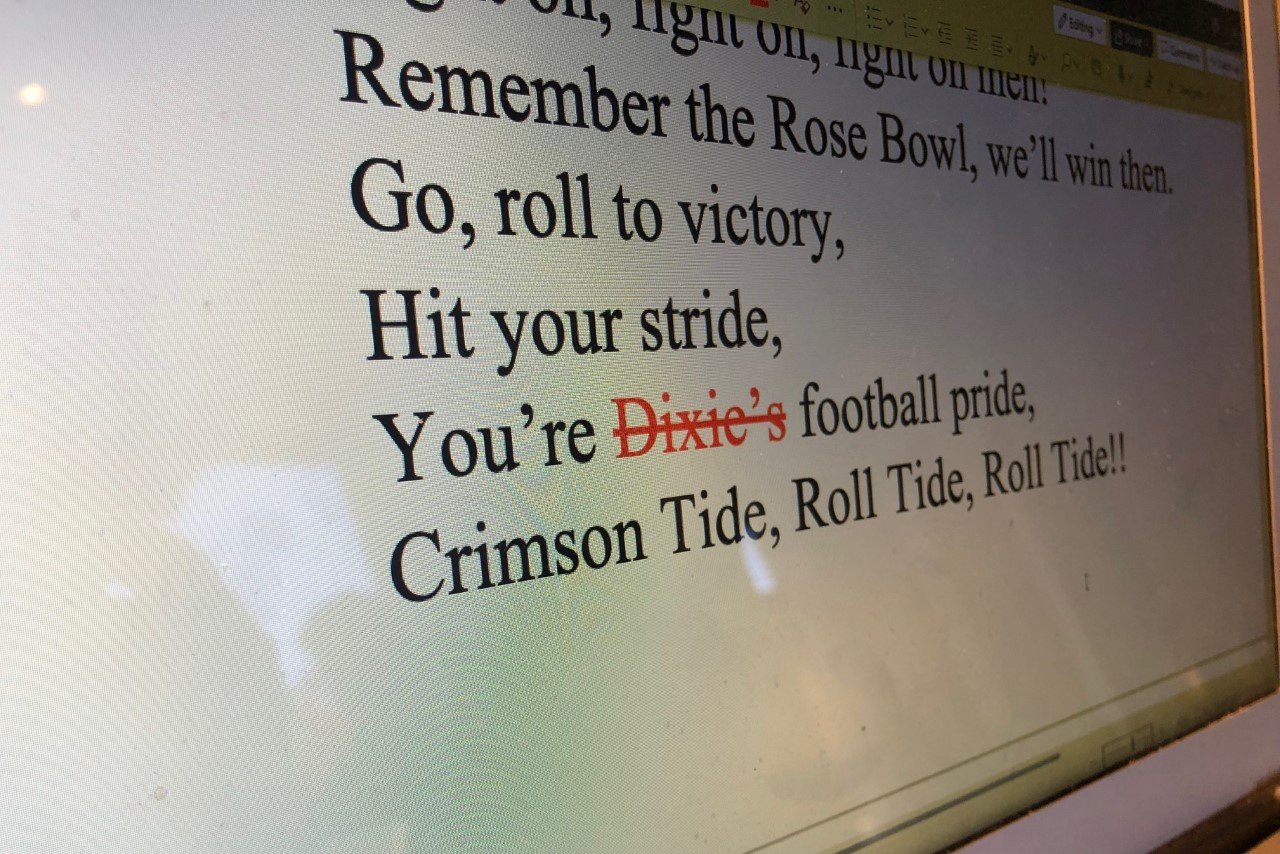

Cassandra Simon, an associate professor of social work at the University of Alabama, has never attended a university football game in her 22 years working there. She was put off by the penultimate lyric in the university’s fight song: “You’re Dixie’s football pride.”

The fight song, “Yea Alabama!” is largely associated with the Crimson Tide, one of the most successful football programs in NCAA history. But it isn’t exclusively played at football games; according to Alabama’s website, it plays “after every score at a sporting event.”

“For me, it would be difficult to be there rah-rahing and the team makes a touchdown, and then they start playing the song, and then I have to stop,” said Simon, who is Black.

In March 2021, she, along with other members of the Black Faculty and Staff Association, officially requested that the university remove the word “Dixie” from the lyrics.

The word refers to the antebellum South and is often seen as offensive for “evok[ing] a very nostalgic and romanticized view of slavery,” historian Tammy Ingram explained to CNN in 2020. Though its origins are disputed, it was used in minstrel shows beginning in the mid-1800s, solidifying its racist connotations, she said.

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests following George Floyd’s murder in 2020, "Dixie" was excised from names across the country. The iconic New Orleans Dixie Brewery changed its name to Faubourg Brewing Co.; Dixie State University, improbably located in St. George, Utah, became Utah Tech University; and, perhaps most notably, the country band the Dixie Chicks dropped the word entirely, rebranding themselves simply as The Chicks.

Now Simon wants the University of Alabama to follow the trend. “Yea Alabama!” was adopted in 1926, “pointedly before persons of African descent were allowed to be here at any time as anyone, except as laborers, paid and unpaid and enslaved persons,” her letter to the administration read. “Thus, we recognize that the use of the term ‘Dixie’ in the fight song is reflective of those times and was not written to send a direct message to Black Americans today. But it does. And not a pleasant one.”

She suggested the word be replaced with ’Bama, which is used as a descriptor earlier in the song: “Yea, Alabama! Drown ’em Tide! / Every ’Bama man’s behind you.”

She suggested the word be replaced with ’Bama, which is used as a descriptor earlier in the song: “Yea, Alabama! Drown ’em Tide! / Every ’Bama man’s behind you.”

Her letter prompted several meetings with administrators but not much else; according to Simon, Alabama’s leaders wanted to see more evidence that students wanted the change before moving forward—a request that Simon sees two ways.

“I know that it is important for our students to have a say in what is present on campus, what is happening on campus,” she said. “But keep in mind students rotate out every four to five years, and so that’s a way the university can continue to not address issues.”

University officials also countered that “Dixie” wasn’t an inherently racist word because there are people named Dixie and companies with the word “Dixie” in their name, she recalled. And they argued changing the lyrics might raise issues with the song’s copyright, Simon said.

“It was stuff like, ‘But what about people named Dixie?’” she said. “I was like, that doesn’t have anything to do with this.”

The University of Alabama declined to respond to a list of questions from Inside Higher Ed regarding efforts to remove “Dixie” from the song.

Student Activism

Students became involved in the project, now dubbed the Delete Dixie Initiative, through a course Simon teaches called Honors Oppression and Social Injustice, which requires completion of an activism or advocacy project. When she told her fall 2021 class about her attempts to get the lyric changed, several students decided to take on the issue as their advocacy assignment. They have since created an informational video, a website and a petition to have the name changed. (This paragraph has been updated to correct the semester in which students got involved in the project.)

Elizabeth Prophet, a junior majoring in social work who took part in the project, said that she didn’t know the connotations of the word “Dixie” when she first arrived at Alabama. Now that she has researched its history, she wants everyone to know.

“I wasn’t aware of the history, like I think many of the people on this campus aren’t, but now that I am, I feel that it’s my responsibility … [to] hear that information and take that information and act on it,” she said.

Another student involved in the effort, Eyram Gbeddy, a sophomore studying political science, said he knew about the “Dixie” connotations before he came to Alabama but didn’t believe he had the resources to tackle the fight song on his own. He became involved in Simon’s effort as a member of the Black Faculty and Staff Association Ambassadors, a student group that aims to bridge the gap between Black employees and students at Alabama.

Alabama officials have yet to respond to the students’ efforts, Prophet said—which is why the group decided to take the campaign public. Now they are planning to conduct presentations for different student organizations about why the word is considered offensive, in the hopes of getting more supporters to sign the petition, which currently has 256 signatures.

Still, it’s unclear how many students need to sign on before administrators will consider the proposal. Prophet worries that the only thing the university will respond to is negative attention and press.

“It seems that, to cut through a lot of that red tape, you have to start a stink on campus,” she said. “Unfortunately, until you put that sort of pressure on the university, they’re not going to listen to the faculty and staff, and they aren’t going to listen to students.”

Gbeddy said he is “cautiously optimistic” that their movement will eventually produce results, but he agreed with Prophet that the university doesn’t seem particularly eager to address the issue.

“If they wanted to, they could very, very easily meet with us. We want to meet with them, but I think they’re trying to avoid us,” he said.

A ‘Woke Agenda’

Not everyone on campus is enthusiastic about updating the fight song. In fact, those who want to “protect” the current lyrics may outnumber those who want to change them. A counterpetition, started when its creator saw an article in Alabama’s student newspaper about the Delete Dixie Initiative, has garnered 631 signatures—more than twice as many as the original petition.

“The word Dixie has nothing to do with racism. It has everything to do with being proud of where you’re from,” wrote the petition’s creator, Henry Roberts. “Dixie is nothing more than a synonym for the South with the connotation of home for millions of people. If we have to do away with Dixie in our fight song, then surely they’ll try to do away with “Dixieland Delight’ next, eroding one Alabama tradition after another, an outcome most every fan would oppose.”

(“Dixieland Delight” is a 1983 song by the country band Alabama that plays during the fourth quarter of University of Alabama football games. According to the Delete Dixie Initiative’s website, the coalition is not asking the university to stop using “Dixieland Delight” because it is not “officially associated” with the university, as “Yea Alabama!” is.)

Commenters on Roberts’s petition have echoed his argument that “Dixie” is not an inherently racist term. They equate removing it with erasing history and caving to a “woke agenda.”

“The term here represents our region, to me. When I think ‘Dixie’s football pride,’ I think ‘Alabama is the top-tier of the [Southeastern Conference Football].’ Use of the word in our fight song has no correlation to slavery,” wrote one signatory, Greg Keeton.

“A few woke students at the University think they are the majority,” wrote another, Kent Montginery. “Hopefully, the real majority won’t cave in to these clowns.”

Removing Offensive Terms

Students at other colleges have successfully pressured administrators to remove offensive language on campuses, including the names of buildings or programs, as a result of the racial reckoning prompted by Floyd's killing. For example, in 2020, a student government proposal at James Madison University in Virginia resulted in the renaming of three buildings that bore the names of Confederate military leaders. Bowling Green State University removed actress Lillian Gish’s name from the campus’s theater in 2019 after students complained about her role in the 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, which contains blackface and other racist imagery. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Board of Trustees lifted a moratorium on renaming buildings in 2020 and, prompted by student and faculty activists, subsequently voted to remove the names of three proponents of white supremacy from campus buildings.

According to Matthew Dennis, an emeritus professor of history and environmental studies at the University of Oregon, altering the fight song is slightly different from changing a building name on campus. Its association with athletics means that it may affect fans beyond the immediate University of Alabama community.

“I have no intimate knowledge of Tuscaloosa, a place I’ve never been, but I imagine that if it’s part of their fight song, then that fight song is probably used to celebrate their football team, and when you start getting into athletics, especially in football in Alabama, you’re getting into a public arena with much higher stakes,” he said.

Still, as more universities face similar demands, the process for evaluating such name changes is becoming more formalized. The process now often involves a committee of stakeholders, including students, alumni, faculty, staff and others, who research the name to determine whether it reflects the college’s values.

Dennis believes that’s the best option in this case as well.

“Make a decision based on knowledge and equity, and whatever that is is going to be defensible,” if controversial, he said.

It’s unclear whether the University of Alabama has an official process for evaluating proposed name changes and similar student requests. In February, officials changed the name of Graves Hall—the College of Education building named after former Alabama governor and Ku Klux Klan leader Bibb Graves—to Autherine Lucy Hall, in honor of Autherine Lucy Foster, the first Black student to attend the university. CNN reported at the time that the process involved consulting with numerous scholars of Alabama history but not with “students and others on campus.”

According to Prophet, removing “Dixie” isn’t the only effort the group plans to undertake to address institutional racism at Alabama. Both she and Gbeddy said the university lags behind peer institutions in tackling its own history of racism; Gbeddy noted that the sororities on campus were only required to desegregate nine years ago.

“Deleting ‘Dixie’ is sort of our first step,” Prophet said. “This is starting a conversation about the legacy of slavery, the legacy of the Confederacy and just the legacy of racism on campus.”