You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Elizabeth Aries’s book chronicles the effects of affirmative action on dozens of students, Black and white, high and low income, as they move from college into their 30s.

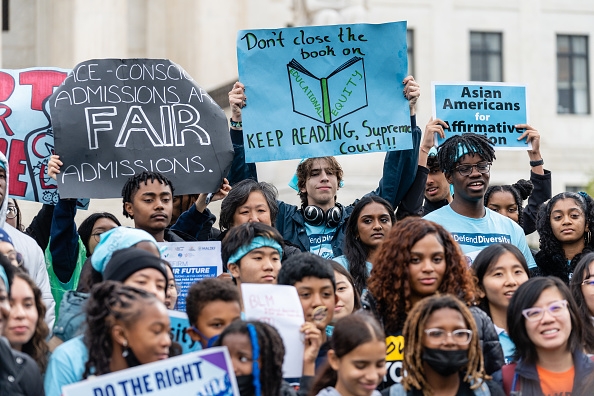

The Washington Post / Contributor / Getty Images

In 2005, Elizabeth Aries started work on a book that chronicled what 58 first-year Amherst College students—Black and white, affluent and lower income—learned from racial and class diversity. Her study, which references other groups but doesn’t focus on them, emphasized the value of campus diversity at elite colleges. Her work was published as Race and Class Matters at an Elite College (Temple University Press). Four years later, Aries interviewed the same students about their diversity experiences as they graduated. Now she has re-interviewed her participants to see how and to what extent race and class continue to play a role as they move into adulthood.

The results appear in The Impact of College Diversity: Struggles and Successes at Age 30, also published by Temple. In the book, Aries, the Clarence Francis 1910 Professor in Social Science at Amherst, outlines how and why affirmative action matters not just in the admissions decisions of colleges, but in the experiences of Black and white students to age 30.

Aries concludes her study with a discussion of why elite colleges have been beneficial in promoting upward mobility in lower-income students, and the importance of achieving equity and inclusion in making diversity initiatives successful.

She answered questions via email.

Q: Why did you pick 30 as the age of your research subjects?

A: Markers of adulthood such as leaving home, marriage and parenthood are occurring at later ages than they did 50 years ago. Psychological research has shown that for most college graduates, the decade [of] the 20s has become a distinct period of development before adulthood is reached. These years are marked by continued identity exploration; exploration of job options; possible graduate school enrollment; changes of residence; fluctuations between being single, dating and cohabitation before committing to marriage; and a focus on self-development. For most by age 30, this period of instability ends and people feel they have reached adulthood. Thus, I waited to do my follow-up interviews until my participants were age 30 and would be at the end of this transitional period and the beginning of their adult years.

Q: What were your major findings?

A: At age 30, 81 percent of the Black and white Amherst graduates in my study reported having learned about race and racism through their regular interactions with college classmates of a different race. Hearing about Black classmates’ lived experiences of race opened the eyes of white graduates to the harm of racial prejudice and discrimination that their Black classmates had endured, and heightened their awareness of their own racial privilege.

Through experiences with racism on campus, Black graduates acquired coping strategies to deal with racial prejudice. As a small minority, they learned how to be comfortable when they found themselves to be the only Black person in the room. They also learned to be bicultural—to be attentive to and adjust their presentation and behavior in order to fit in and be successful in a predominantly white environment. These skills helped enable their success in facing racism in the predominantly white work world they had entered.

Lower-income graduates reported adjusting to a new, more affluent culture at Amherst and also spoke of becoming bicultural. They learned from affluent classmates the rules of the game—the skills, knowledge, tastes and preferences that would enable them to fit into and function comfortably in an upper-middle-class world. Seeing classmates strive for pre-professional internships and/or acceptance to graduate school increased lower-income graduates’ aspirations to seek such opportunities for themselves. Two-thirds of lower-income graduates reported drawing on connections they made at Amherst with people of a higher social class for access to desired internships, graduate programs and jobs, and those connections helped lead to their upward social mobility.

Q: Were there any surprises?

A: I was most surprised by the data on the upward mobility of the lower-income graduates. Sixty-five percent had gone on to attain graduate degrees. Most had chosen degrees that led to the highest earnings: 57 percent of lower-income white and 22 percent of lower-income Black participants had gone on to attain a doctoral-level degree (Ph.D., M.D., J.D.) at one of the top graduate schools in the country. Another 44 percent of the Black graduates had acquired M.B.A.s from top business schools in the country or had gone into finance and worked for a prestigious investment bank. The upward mobility of the lower-income graduates was particularly striking to me because my earlier research showed that for many of the lower-income graduates, their time at Amherst was a real struggle both academically and socially. When they entered the college in 2005, many fewer resources existed to create an inclusive community and to provide the support needed to help them be successful.

Q: The Supreme Court is expected to rule against affirmative action in two cases it is considering. What should the Supreme Court do, in light of your findings?

A: A decision by the Supreme Court to ban race-conscious admissions would be catastrophic to the attainment of upward social mobility for members of underrepresented groups. We already have data from states—such as Michigan and California—that have banned the consideration of race in admission. A precipitous drop in the proportion of students from underrepresented groups has followed. The enrollment of Black students dropped 44 percent after the ban on the use of race in admission in Michigan. At the most selective state campuses in California, the proportion of African American and Latinx students dropped by 50 percent. Unable to attend the flagship universities, many students from underrepresented backgrounds went on to less selective schools. Without the many resources offered to students at the most selective colleges, they showed lower degree attainment, and ultimately lower wages, thus increasing socioeconomic inequities.

Without allowing for a consideration of race as one factor of many in a holistic consideration in admissions, the Supreme Court would also make it extremely difficult for colleges to achieve the crucial educational benefits that derive from students’ daily interactions with classmates whose racial backgrounds, experiences and views differ greatly from their own. Most white students enter college having grown up in predominantly white communities and having attended predominantly white schools. In my study, interactions with Black classmates awakened them to the realities and harm of racism that Black classmates and their families experience regularly. Thirty percent of the white graduates aspired to raise their children, if and when they had them, in a racially diverse environment because they believed strongly in the importance of intergroup contact and feared the outcomes for their children of growing up in predominantly white environments.

Higher education has an extremely important role to play in helping people see things differently and in potentially helping to reduce racial inequality. But this requires cross-race interaction. A considerable body of research has shown that cross-race interaction decreases intergroup prejudice and that participants in cross-race interaction gain knowledge about and feeling of acceptance for people from other racial groups.