You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Declaring that Cardinal Stritch University is in a “no-win situation,” officials announced Monday night that the private, Roman Catholic institution in Wisconsin will close at the end of the spring semester.

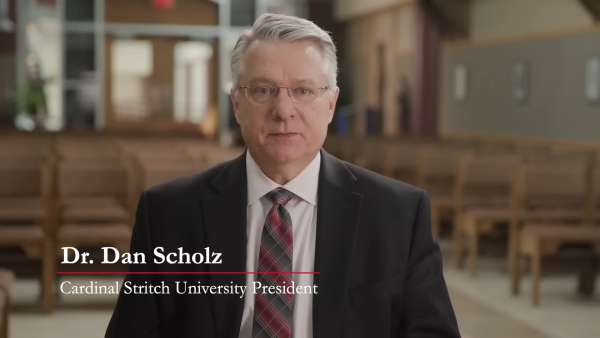

President Dan Scholz said in an announcement posted to YouTube that a number of factors prompted the closure, including “fiscal realities, downward enrollment trends, the [coronavirus] pandemic, the need for more resources and the mounting operational and facility challenges.”

Scholz added that the Board of Trustees had made the recommendation to shutter the university because it “could no longer continue to provide the high-quality educational experiences our students deserve.”

The Sisters of Saint Francis of Assisi, the Franciscan order that established the university in 1937, accepted the board’s recommendation to end operations, Scholz said. Now the institution is poised to cease operations in late May, following commencement, and is developing transfer pathways to help current students enroll elsewhere.

Plunging Enrollment

Scholz’s message echoed many of the statements released by other colleges that have recently announced plans to close, hitting such common themes as financial strain, declining enrollment and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cardinal Stritch University President Dan Schulz announces closure.

YouTube

“We are all devastated by this development. But after examining all options, this decision was necessary,” Scholz said in a somber announcement detailing the reasons for the closure.

The college has been shedding head count for years, with enrollment plunging from more than 5,000 students in 2011 to 1,365 in fall 2021, according to the most recent data from the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. While the lingering effects of the coronavirus pandemic have contributed to anemic enrollment nationwide, Cardinal Stritch’s numbers have been in free fall for a decade.

The university’s most recent financial composite score from the Department of Education was 2.2, above the 1.5 threshold that indicates financial responsibility on the 1.0 to 3.0 scale. However, publicly available tax documents show the university has been running at a financial deficit for roughly a decade, which coincides with the enrollment decline that precipitated the closure.

University officials declined to answer questions from Inside Higher Ed. But one former employee, speaking on the condition of anonymity, questioned the roles that revolving executive leadership and a deal with a for-profit enrollment company may have played in the demise of Cardinal Stritch.

The insider argued that operational and academic issues were not adequately addressed over the last decade as Cardinal Stritch shuffled through three presidents and saw turnover at various other top executive posts as well. In that time, donations to the university slowed, the source said, yet it continued to offer generous athletic scholarships even as declining enrollment shrank much-needed tuition revenue.

By the time Scholz was installed as president in 2021, many of the problems were irreversible, the source said: “I believe his heart was always in the right place, but he inherited quite a mess.”

Another factor, the anonymous former insider said, was “a sticky relationship” established in 2013 with Synergis, a for-profit recruitment and enrollment company. The source suggested the company’s recruiting failures led to significant enrollment losses, which “wrecked the financial projections.” Ultimately, Cardinal Stritch paid to break the contract with Synergis, the source said.

Synergis CEO Norm Allgood dismissed the idea that his company played any role in the closure.

"Our agreement with Cardinal Stritch ended eight years ago. Cardinal Stritch University made a decision to pursue a more traditional approach to student recruitment and therefore reached an agreement with Synergis to buy out the contract," Allgood wrote by email. "For anyone to suggest we played a role in the university’s downfall is misguided."

Closures and Mergers Continue

The closure of Cardinal Stitch University comes as many other institutions—secular as well as religious—struggle with market forces that have battered the higher education sector in recent years.

“This is a sadness for many of us who know and love the Sisters of St. Francis and the good work they’ve done through Stritch,” Dennis Holtschneider, president of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “Catholic higher education is facing the same challenges as all of American higher education, but perhaps just a bit more as colleges like Stritch stretch their budgets to educate students who wouldn’t have an opportunity otherwise. Putting aside money for a rainy day hasn’t always been a priority for groups like the Franciscans. It’s a noble mission and a challenging business model.”

In recent months, several other colleges with a religious affiliation have announced plans to close, including Iowa Wesleyan University, Presentation College, Finlandia University, Holy Names University and Living Arts College. Others, like Medaille University, have been absorbed by more financially viable institutions. And some institutions are clinging to life amid ongoing business issues, such as The King’s College and Birmingham-Southern College, both of which have announced serious financial concerns that may lead to eventual closure if not immediately addressed. (This paragraph has been updated to clarify Finlandia University's religious affiliation.)

Cazenovia College, which is nonsectarian but was originally sponsored by the Methodist Church, has also recently announced it will close, citing financial and enrollment issues common across the sector. (This paragraph has been updated to reflect Cazenovia's religious roots.)

Those closures are set against the backdrop of ominous findings from Fitch Ratings, released in December, that predicted “more operating woes” for U.S. colleges and universities. The agency described the sector outlook for higher education in 2023 as “deteriorating,” due to rising costs and wages alongside sluggish enrollment—a downgrade from its neutral outlook for higher education in 2022.

Despite the market forces driving closures and mergers, many leaders remain optimistic, according to the results of the annual Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Presidents, released this week. While 27 percent of presidents surveyed said their college should consider a merger within the next five years, most were positive about their institution’s financial state, with nearly eight in 10 respondents indicating they believe their college will be financially stable over the next decade.