Free Download

Fewer than a quarter of college and university technology leaders are very confident that their institutions can prevent ransomware attacks. Most are struggling to hire and retain technology employees. And just four in 10 say they believe senior administrators at their institution have made digital transformation a high priority, even after the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the importance of agility and adaptability.

Those are among the findings of Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 Survey of Campus Chief Technology/Information Officers, its first-ever such survey. The technology survey, conducted in partnership with Hanover Research and released in conjunction with the Educause annual conference that begins today, joins Inside Higher Ed’s studies of other key campus leaders, alongside those of presidents, provosts, chief academic officers and admissions directors. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

Technology has played an increasingly important role at most colleges and universities in recent years, reshaping how institutions communicate with employees and students, manage their business processes, operate their facilities, and, to varying degrees at different institutions, deliver their education. At most colleges, technology isn’t the strategy but is increasingly an enabler of it.

The survey sought to gauge how the seniormost technology leaders on campuses—most of whom carry the title of either chief information officer or chief technology officer—view their institutions’ efforts to use the ever-growing array of technological tools and capabilities to carry out their educational and other missions and operate more effectively and efficiently. (This article uses the terms “CIO” and “CTO” interchangeably to refer to the survey’s respondents.)

More About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed’s 2022 Survey of Campus Chief Technology/Information Officers was conducted by Hanover Research. The survey included 175 chief technology or information officers from public, private nonprofit and for-profit institutions. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

On Wednesday, Nov. 9, at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Please register here.

The Survey of Campus Chief Technology/Information Officers was made possible in part by advertising support from Class Technologies, Huron Consulting Group, Jenzabar and Ready Education.

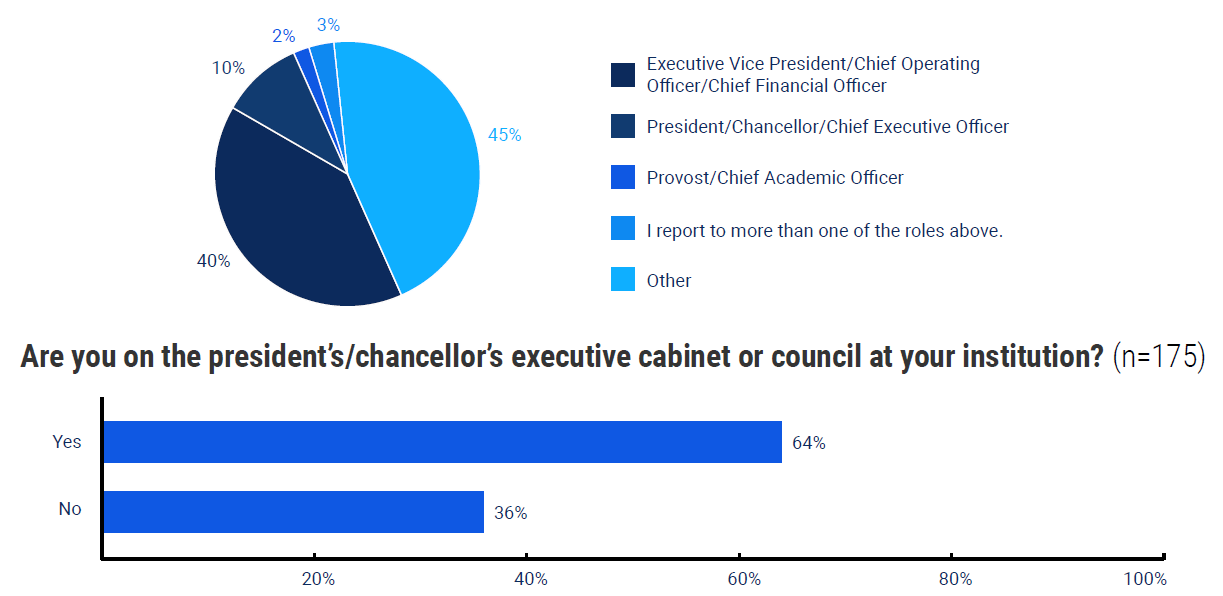

A bifurcated picture emerges from the 175 respondents. At about two-thirds of colleges, the chief technology or information officer is on the president’s cabinet, with about one in six of those added during the pandemic. Technology leaders at those institutions are far likelier than their peers to say that their institution has made digital transformation a priority (52 percent versus 24 percent), and far less likely to agree that senior administrators at their college treat the IT unit “more like a utility than a strategic partner” (42 percent versus 70 percent).

IT leaders who are in the executive cabinet are significantly likelier to agree that their institution “makes data analytics a strategic priority” (68 percent versus 45 percent) and “has buy-in across departments regarding the importance of sharing and analyzing data” (60 percent versus 38 percent).

Other highlights of the survey’s findings include:

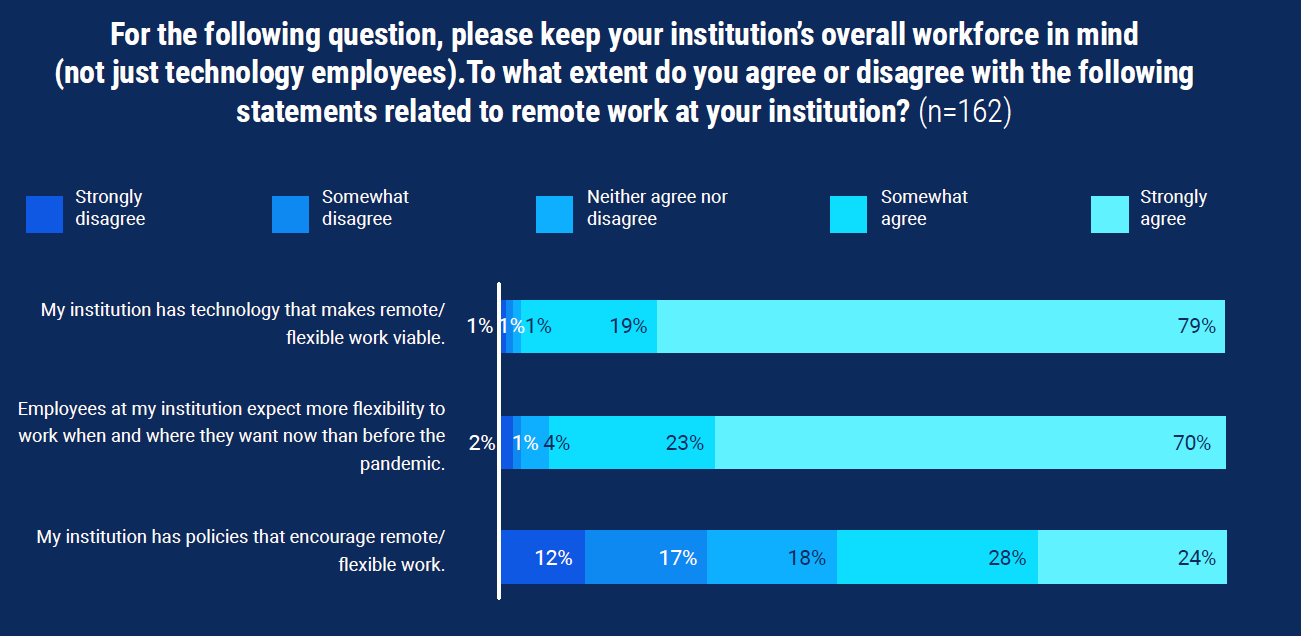

- Most respondents strongly agree that their institution has technology that makes remote/flexible work viable for employees, but only half agree that their institution has policies that encourage remote/flexible work.

- CIOs are generally upbeat about their colleges’ ability to offer high-quality virtual instruction, and most agree that their institution upped its game during the pandemic. Tech leaders also generally agree that their institutions provide technical and instructional design support for faculty members but don’t believe they give instructors credit for digital pedagogy or teaching with technology.

- Fewer than a quarter of tech leaders are very or extremely confident that their cybersecurity policies can prevent ransomware attacks.

- Few CIOs report that their institution has made meaningful investments in cutting-edge technologies such as virtual reality or immersive learning (38 percent say they have at least begun investing) or adaptive learning (44 percent say they are considering investing).

Why Structure Matters

The survey’s questions and results can be divided into several broad categories: how technology is managed and prioritized within institutions, including budgetarily; campus technological infrastructure and support; and the role technology plays in campus work and in teaching and learning.

Reporting lines and structures are rarely newsworthy. But in many organizations, including colleges and universities, how decisions are made and who is involved in making them can help determine what decisions are ultimately made, which matters a lot. So in crafting this initial survey of chief technology/innovation officers, Inside Higher Ed and Hanover sought to understand institutions’ structure for managing the role of technology.

Two key questions suggest that CIOs and CTOs are generally well positioned to be influential in their institutions: the vast majority report to either the most senior administrative officer (45 percent) or directly to the president (40 percent), with most of the rest to the provost/senior academic officer. About two-thirds are on the executive cabinet or council at their institution, with 15 percent of those joining the president’s team of closest advisers during the pandemic.

CIOs at public doctoral universities are the likeliest to report directly to the president, at 52 percent, followed by those at private master’s and baccalaureate institutions (41 and 44 percent, respectively). CTOs at community colleges (54 percent) and private doctoral institutions (57 percent) are likeliest to report to the executive vice president or chief operating officer. Four in five tech leaders at public doctoral institutions (79 percent) are on the president’s cabinet, with the other sectors all in the 60 to 65 percent range.

CIOs at nondoctoral universities and the central IT units they lead tend to have a wider set of responsibilities than their peers at public and private research universities.

Virtually all CTOs are responsible for administrative technology, telecommunications and academic technology. But while between two-thirds and three-quarters of CIOs over all say they provide support for online education, media services, institutional research and campus teaching and learning centers at their institutions, tech leaders at two-year and four-year nondoctoral institutions are much more likely to do so than their doctoral university peers.

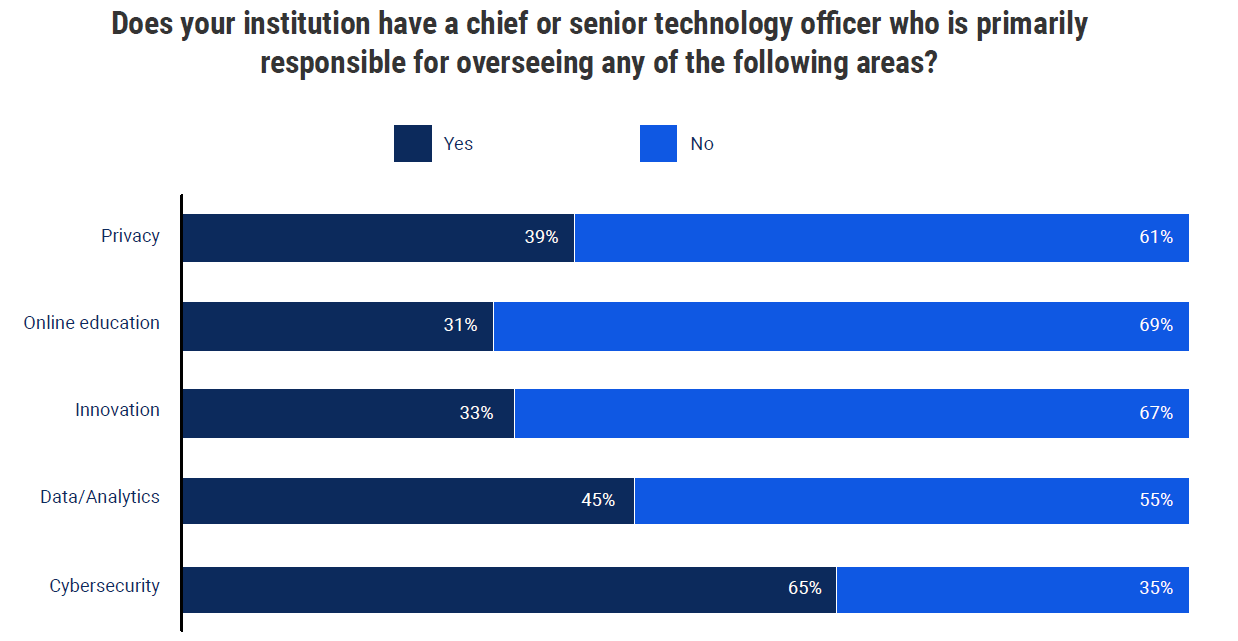

Bigger (and wealthier) institutions are also much more likely to have specific senior officers responsible for key functions such as cybersecurity, data analytics and online education. The overall proportion of institutions with a chief point person on these issues can be seen below.

But the gaps between institution types are significant: 43 percent of public doctoral university CIOs say their institution has a chief officer responsible for online education, compared to 24 percent of community colleges and 29 percent of private baccalaureate colleges. Nine in 10 public doctoral universities and eight in 10 private doctoral institutions have a cybersecurity czar of sorts, compared to 70 percent of public master’s institutions, 59 percent of community colleges and about half of nondoctoral four-year private institutions.

Budgets and Human Effort

Another set of questions sought to understand the scope (and cost) of campus technology resources and how they were distributed across the institution.

The budget data showed enormous, and unsurprising, variation, given the great differences in size and complexity of institutions in the higher education ecosystem. A majority of colleges and universities reported centralized IT budgets of between $1 million and $5 million (37 percent of the total pool of institutions) or $5 million and $10 million (22 percent), with 12 percent of institutions (and a quarter of four-year baccalaureate colleges) spending less than $1 million and 16 percent (68 percent of public doctoral institutions) spending at least $20 million.

The 2021–22 academic year was one in which many colleges faced enrollment challenges but benefited from federal aid to help institutions and students navigate the COVID-19 pandemic.

About four in 10 CIOs (42 percent) said the central IT functions at their institution experienced a budget cut in the 2021–22 academic year. Those reductions were disproportionately reported at public master’s universities (by 65 percent of CTOs at those institutions) and at private doctoral universities (57 percent).

Those institutions were also likelier than their peers to expect their 2022–23 budgets to shrink below their 2021–22 levels. Over all, more technology officers expected their 2022–23 budgets to increase (31 percent) than to decline (22 percent), but the reverse was true for private doctoral universities (26 percent expected the 2022–23 budget to be lower versus 17 percent higher) and public master’s institutions (35 percent predicted lower versus 15 percent higher).

For many years, Kenneth C. (Casey) Green published the Campus Computing Survey, which was last produced in 2019; Inside Higher Ed’s new survey aims to partially fill the gap left in its wake. Green said the anticipated reductions in IT budgets are “striking—and disappointing … given that IT assumed an even larger and even more essential role in instruction and campus operations during the pandemic.”

One of the perennial discussions about how technology is managed on campuses is about the degree to which it should be centralized as opposed to left to individual campus departments and units to oversee. Many discussions about shared services and other attempts to centralize technology and other services run aground amid arguments by faculty and staff in individual departments that their needs take a back seat.

This survey sought to gauge how colleges and universities are currently allocating their technology resources, centrally or dispersed through the institutions.

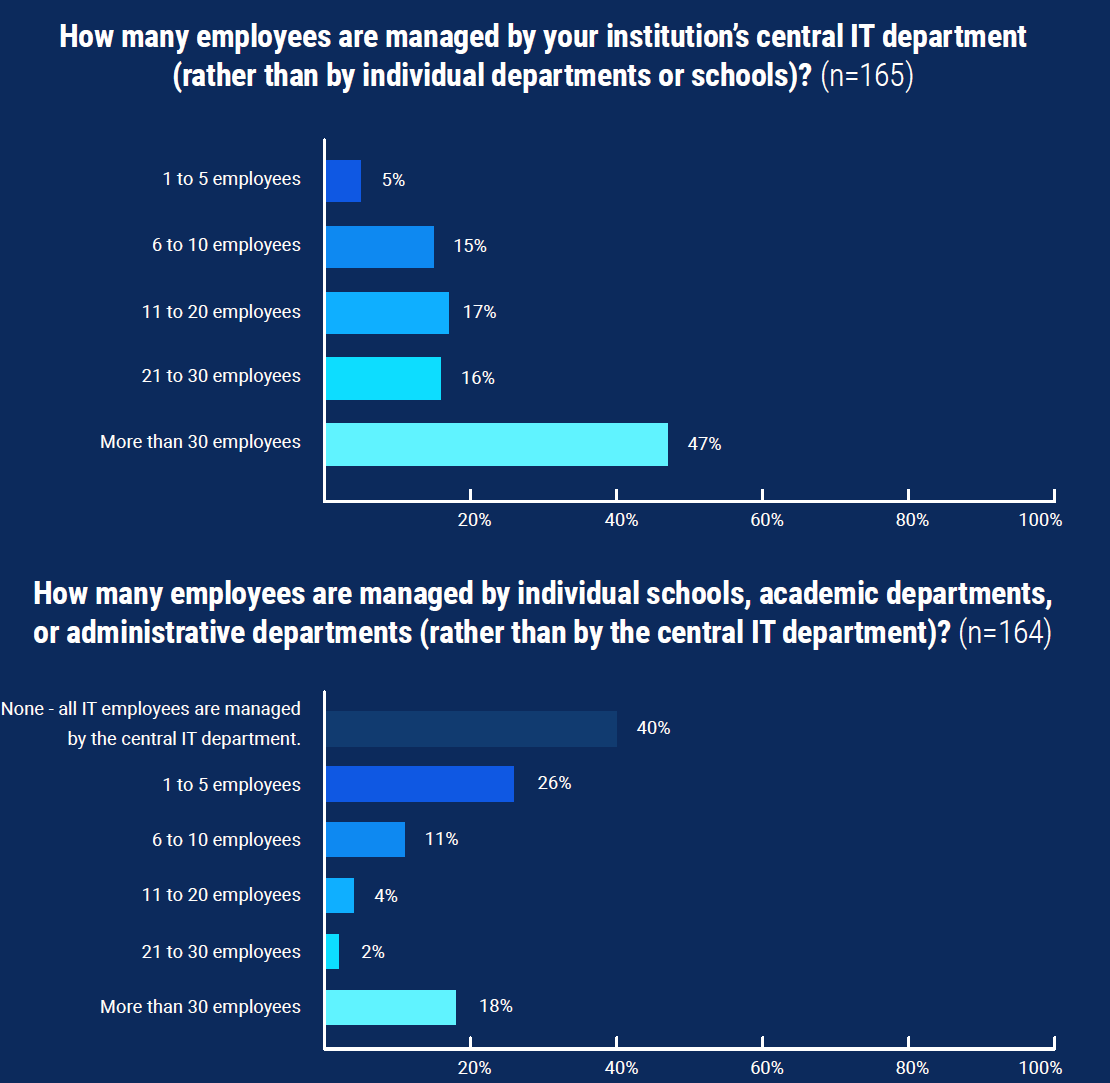

CIOs were asked how many technology employees were managed through the central IT unit as opposed to by individual academic departments and administrative units, as seen in the charts below.

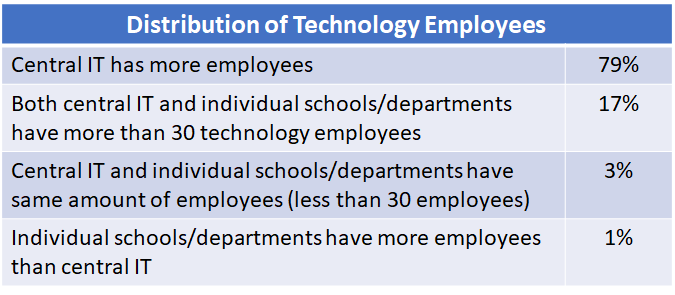

About four in five CTOs (79 percent) reported that their central IT unit had more employees than were managed by disparate units at the institution. But about a fifth of CIOs—mostly at larger institutions with dozens of technology employees—said individual units employed as many or more employees than did central IT.

At most institutions, the central IT unit manages most key technology functions, such as setting technology policy and ensuring cybersecurity (90 percent each), managing infrastructure (82 percent) and personal devices (64 percent), and providing tech support for students (69 percent).

But functions such as hiring of technology employees, managing specific technology applications for both academic and nonacademic purposes, and technology support for faculty members are split more equally between central IT and the individual units in question.

CIOs from public doctoral institutions are much likelier than their peers to say that functions such as tech support for students and professors and application management are joint responsibilities between central IT and departments, reflecting the comparatively significant authority of academic and other departments at those institutions.

The Role of the CTO and Technology Decision-Making

Arguably more important than the details of how institutions’ technology operations are structured and supported is the question of how they make decisions about the role of technology, which ultimately is what matters most.

But the survey’s data suggest that the two issues are interconnected.

Several questions sought to gauge how technology leaders envision their roles and that of technology and innovation at their institutions—and, importantly, how they think others view it.

CTOs answered one set of queries about how leaders at their institution viewed the central IT unit.

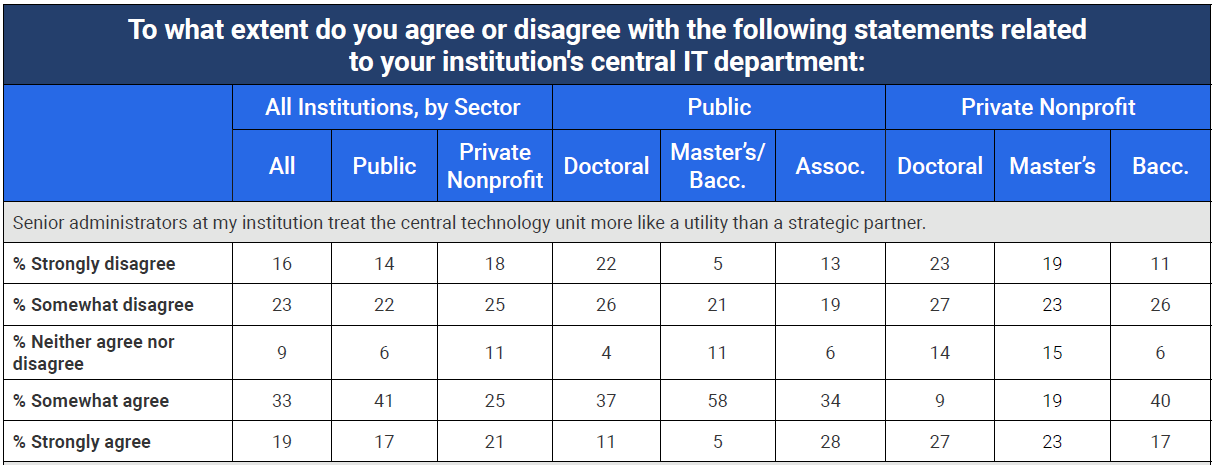

Over all, about half of respondents strongly (19 percent) or somewhat agreed (33 percent) that “senior administrators at my institution treat the central technology unit more like a utility than a strategic partner.” Thirty-nine percent disagreed.

There were sharp divisions by sector: tech leaders at community colleges, public master’s universities and private baccalaureate colleges were likeliest to believe leaders saw technology departments as units to carry out specific functions rather than as influential in setting direction.

The gaps were particularly wide based on campus structure. A full 70 percent of CIOs at colleges where they were not in the cabinet and 60 percent who did not report to the chief executive officer said administrators viewed them as utilities, compared to about 40 percent where the reverse was true.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, behavior follows perception. The survey asked CTOs whether their units performed more like utilities or like strategic partners at their institution, and while nearly six in 10 over all said their unit played a key role in strategy setting, technology leaders at public master’s universities (64 percent) and community colleges (41 percent) were most likely to agree at least somewhat that their department operated more like a utility.

CIOs who sat on administrative cabinets or reported directly to the president were also much more likely to say their department behaved like a strategic partner.

“Every tech leader at a higher education institution has as a primary obligation the responsibility to identify ways to ensure that the maximum proportion of resources are going to the academic enterprise.”

Similar patterns emerged around a set of questions about “digital transformation.” That buzzword means many things to many people. Educause defines it as “a series of deep and coordinated culture, workforce and technology shifts that enable new educational and operating models and transform an institution’s operations, strategic directions, and value proposition.”

A project at Brown University characterizes it as “the purposeful creation of a cohesive digital ecosystem that provides faculty, staff, students and alumni with the tools and capacities needed to support education and research, business operations, volunteer engagement, and communications, and which are optimally integrated with each other to support data-sharing and efficient maintenance.”

The survey takes as a starting point—though certainly some people in higher education may dispute it—that most colleges are (or need to be, to varying degrees depending on their missions) on a path to preparing for a more digitally focused present and future.

The survey doesn’t ask CIOs whether they think digital transformation is necessary at their institutions; it’s taken for granted that they do. But they were asked how important digital transformation is for leaders at their institution. Roughly four in 10 said it was either essential (10 percent) or a “high priority” (32 percent), while about one in six said it was either a “low priority” (12 percent) or not a priority at all (4 percent).

There were some differences by sector: the proportion saying it was either essential or a high priority ranged from 31 percent at private master’s universities to 49 percent at public doctoral and private baccalaureate colleges.

But as with the question about utility versus strategic partner, the differences based on the technology structure at the institution were far sharper.

More than half of the CIOs who were in the cabinet at their institution (52 percent) said digital transformation was a key priority at their institution, compared to 24 percent of those who were not in the executive group. And 59 percent of technology leaders who reported directly to the president or chancellor said digital transformation was highly important to their leaders, compared to 32 percent who reported to someone else.

Mark McCormack, senior director of research and insight at Educause, said the organization has tried in reports such as this one to explore how CIOs can be most effective and influential.

Educause’s own research has shown that technology leaders benefit when they report directly to the president or sit on cabinets.

But he said via email that “when institutional leadership fosters a healthy culture of collaboration and partnership, those positions of power and direct access become less essential, and it frees us up to think creatively about other alternative institutional structures and reporting lines (like reporting to the academic officer, which more closely aligns the CIO with the institution’s missional priorities and activities around student success).”

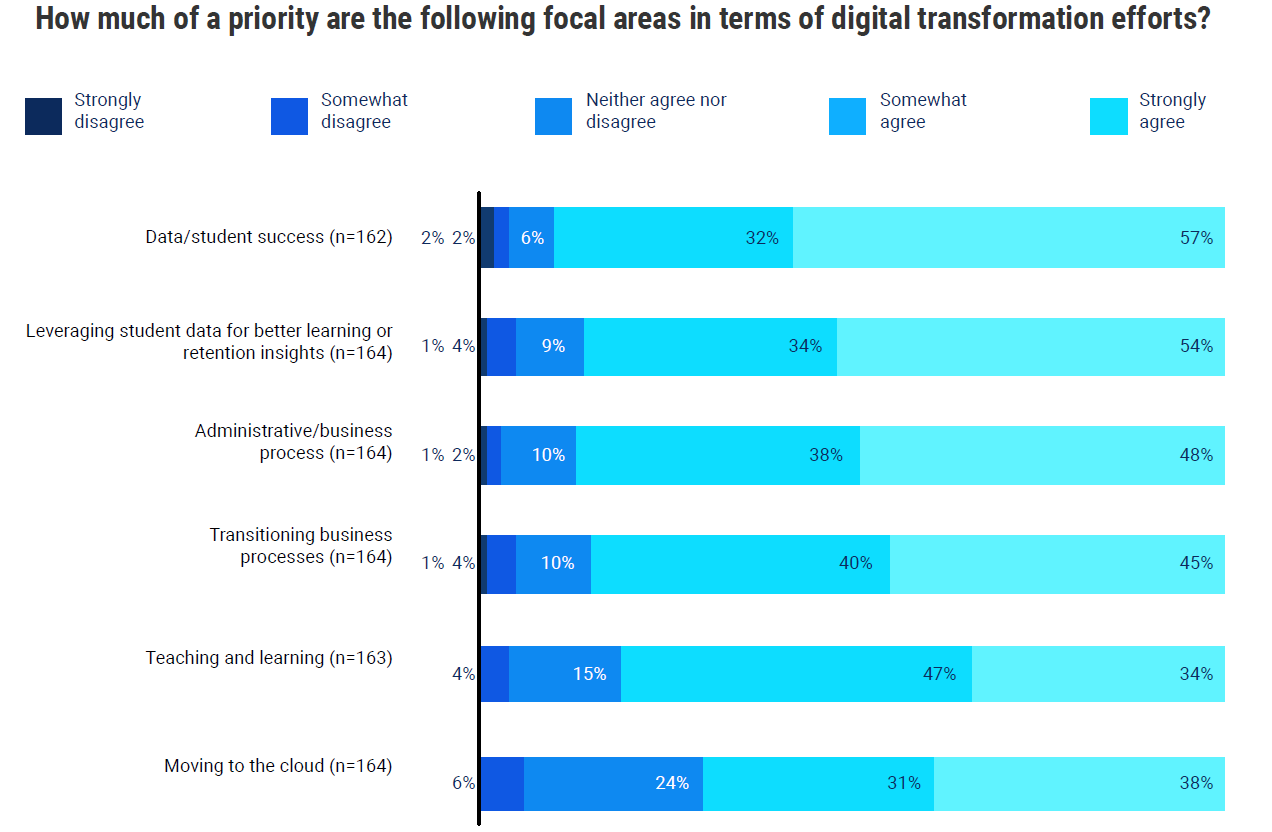

Where do CTOs and their institutions see the most opportunity for digital transformation? The top two priorities relate to ensuring student success, followed by improving business processes and then teaching and learning.

But fewer than two-thirds of CIOs say their institutions have set specific goals for making their institutions more digitally focused, and those who have say insufficient financial investment (65 percent) and resistance among faculty and staff members (60 percent) pose the biggest obstacles.

About a third of CTOs cite goals that are incomplete or ineffective and lack of senior administrative support.

Mark Cianca, who joined Huron Consulting Group as a specialist in higher education last spring after serving as a CIO and in numerous other roles over 35 years at the University of California, said he was surprised that more tech leaders didn’t identify moving their operations to the cloud as a major focus.

Asked which of their core technology systems they had migrated from being run on their own campuses to being run in the cloud through a web-based software-as-a-service platform, 87 percent of CTOs chose their learning management systems and 70 percent cited their customer relationship management software (for communicating with students and other constituents), and just under half identified their human resources and fundraising systems. Far fewer said they’d made that move for budgeting, research administration and student information systems.

Cianca said CIOs increasingly need to be “identifying activities and behavior” their institutions are engaging in that “do not add value to the organization” and are not core to the academic mission. “Every tech leader at a higher education institution has as a primary obligation the responsibility to identify ways to ensure that the maximum proportion of resources are going to the academic enterprise,” he said.

At most institutions, he said, “being in the business of running a data center isn’t part of the academic core.”

Judging Their Own Performance

Another set of questions aimed to gauge technology leaders’ perspective on what they and their institutions do well technologically and where they fall short.

CTOs give themselves the best ratings on elements such as computer networks and data communication (94 percent rate it as excellent or good, 58 percent excellent), user support services (91 percent excellent or good), wireless networks (90 percent), the learning management system (87 percent), and audiovisual-enabled classrooms (86 percent).

They rate themselves least well on IT training for students (24 percent), mobile apps and services for students and employees (45 percent), disaster planning (50 percent), and IT training for instructors (51 percent).

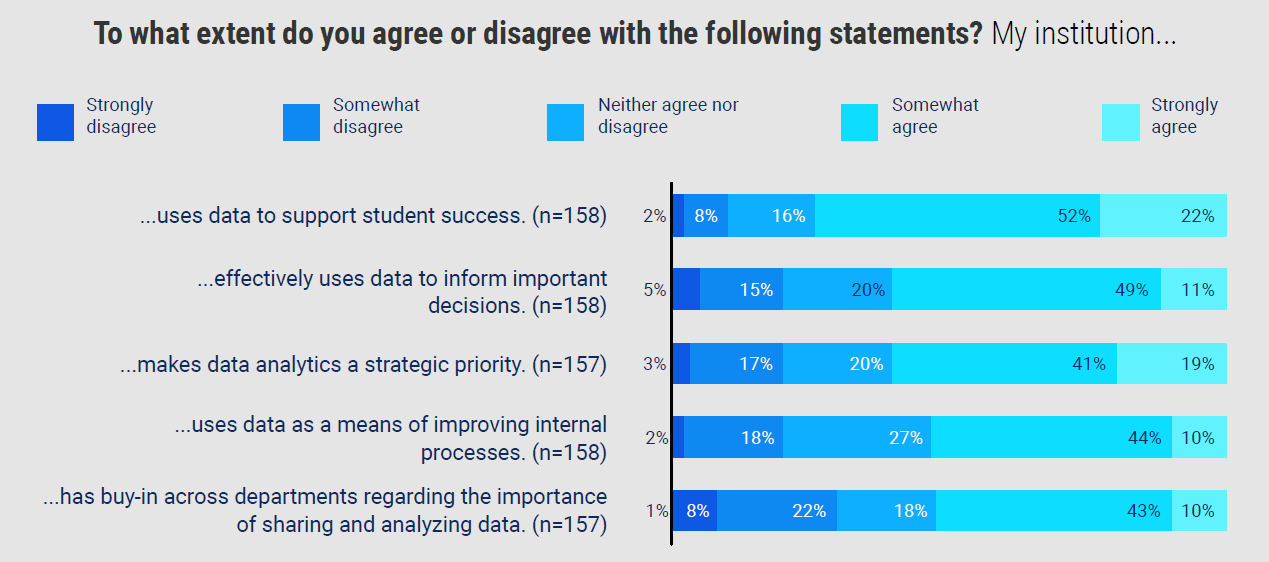

Digging more deeply into a couple key functions, technology leaders acknowledge they have room to improve on how effectively their institutions use and analyze data.

Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) say they believe their institution uses data to support student success.

But only 60 percent say their institutions use data effectively to inform important decisions (only 11 percent strongly agree) or make data analytics a strategic priority (19 percent agree strongly).

Barely half agree that their college or university uses data to improve internal processes or has gained buy-in across the institution about the value of data use and analysis.

Liv Gjestvang, chief information officer at Denison University who previously spent 15 years in learning technology at Ohio State University, said she was heartened by the technology officers’ focus on leveraging data to support student retention and success. But she said via email that areas such as institutional advancement, alumni engagement and enrollment management can all “reap huge benefits from increased data insights in their work, and CIOs and their teams have an opportunity to help align strategies and integrate systems to support data driven insights across the institution.”

Other Findings

The CIO survey produced numerous other important findings. Among them:

Remote work and the IT workforce. Many higher education leaders are worried about employee turnover and burnout, and perhaps no departments are more vulnerable than technology units. While tech employees are comparatively well paid within higher education, gaps between what programmers, engineers and others with digital skill sets can earn on the open market are perhaps wider than is true for most other college and university workers.

More than half of CIOs strongly agree (51 percent, and 33 percent somewhat agree) that they are struggling to hire new technology employees, and 62 percent (27 percent strongly) say they’re struggling to retain employees. Better salaries at other organizations (99 percent) and more flexible remote work policies (53 percent) are the biggest factors in their struggles, with few seeming to think that employees see the work as less meaningful or think the institution is no longer pursuing its mission (9 percent each).

For all employees, CIOs also believe their institutions are well prepared technologically to enable remote work. But the tech leaders are not confident that their institutions have policies that will satisfy the growing number of employees that they believe want more flexible work arrangements, as seen below.

Digital learning and academic technology. Chief technology officers believe their institutions upped their game in digital teaching and learning during the pandemic—with a significant assist from the federal government.

Roughly eight in 10 CIOs agreed that their college or university’s ability to offer high-quality online (84 percent, 42 percent strongly) and hybrid courses (77 percent, 35 percent strongly) “significantly improved” since the pandemic began. Eighty percent also agreed that their institution would “sustain” its ability to offer high-quality virtual learning.

Even more CTOs, 86 percent, agreed that their institution had used money from federal COVID recovery aid to improve its digital learning infrastructure. Most of that money has now been spent, which will force institutions to find other sources of funds to sustain or expand their support for technology-enabled learning.

CIOs rated their institutions much more highly on technical and operational support for learning initiatives than on policies for motivating and rewarding instructors.

Three-quarters or more of tech leaders strongly or somewhat agree that their college provides technical support for teaching (91 percent) and creating (89 percent) online courses and invests in technology and instructional design resources to improve teaching and learning (78 percent).

About two-thirds say their institution has a “climate that encourages experimentation with new approaches to teaching, including with technology” (70 percent) and policies that “protect faculty members’ intellectual property rights for digital work” (67 percent).

The numbers decline further when CTOs are asked whether they agree that their colleges acknowledge the time demands of online courses on faculty workload (61 percent, only 18 percent strongly), provide additional compensation for online course development (45 percent), consider teaching with technology (in-person or online) in tenure or promotion decisions (38 percent), or reward faculty members for contributions to digital pedagogy (35 percent agree, only 8 percent strongly).

Cybersecurity. As colleges and universities face growing numbers of cyberattacks, only 2 percent of CIOs say they are “extremely confident” that their institution’s policies can prevent such attacks, 20 percent are very confident, 59 percent are moderately confident and a full quarter are either “slightly” confident (23 percent) or not confident at all (3 percent).

The vast majority of technology leaders say their institution has cybersecurity insurance, and nearly two-thirds of those (62 percent) say they are satisfied with their coverage. Nearly a third (29 percent) say they have insurance but want to expand it, and about 10 percent don’t have cyber insurance. Most of those say the policies are either too expensive or carry requirements that are too high.

Emerging technologies. Relatively few CIOs say their institutions have gotten serious about cutting-edge technologies. Fewer than one in seven technology administrators say their college or university has made “meaningful” investments in such areas as quantum computing (14 percent), machine learning (6 percent), artificial intelligence (8 percent), adaptive learning (7 percent) or virtual reality/immersive learning (9 percent). Nearly a third of CTOs (29 percent) say their institution has “begun making investments” in virtual reality, more than in any of the others.

Public doctoral institutions are significantly likelier than their peers to have made investments in these areas.

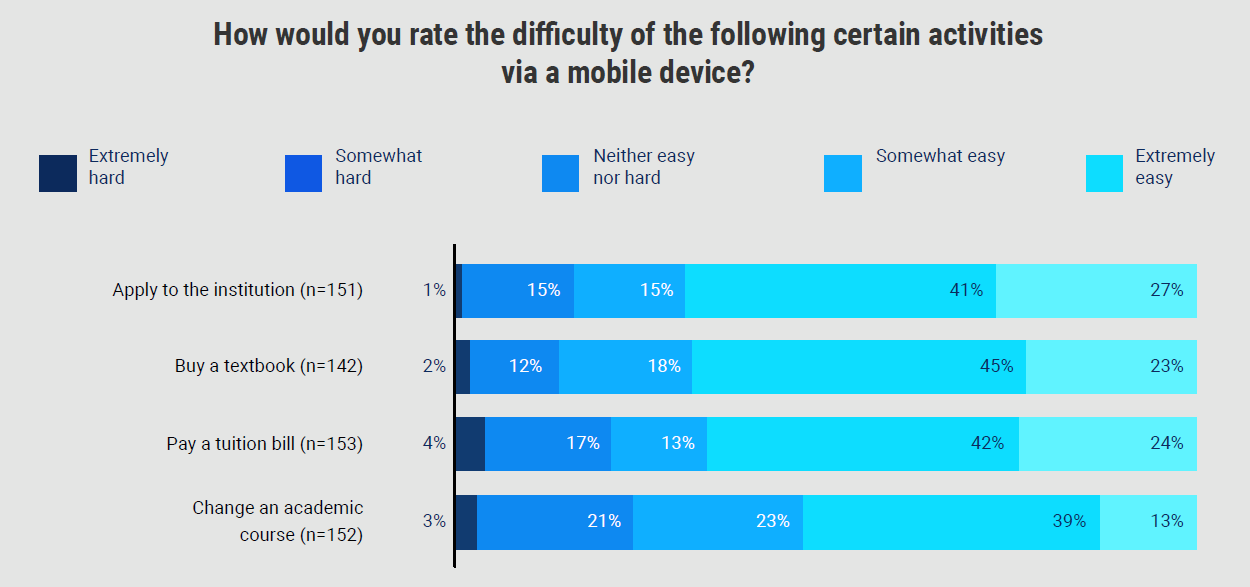

Mobile accessibility. Only about a quarter of CTOs say their college makes it “extremely easy” for students to use a mobile device to perform core functions such as applying, buying a textbook, paying their tuition bill or changing a course. Another four in 10 on average say it is “somewhat easy” to do so.