Free Download

Most faculty members say data-driven assessments and accountability efforts aren’t helping them improve the quality of teaching and learning at their colleges and universities, according to the 2016 Inside Higher Ed Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology. Instead, instructors and a large share of academic technology administrators say the efforts are mainly designed to satisfy accreditors and politicians -- not to increase degree completion rates.

It has been another tumultuous year in educational technology. The past 12 months have seen new ways to deliver education and course materials, new start-ups promising to revolutionize teaching and research, and new questions about the role of technology in and outside the classroom.

In the midst of those new developments, old concerns remain. Faculty members are still worried that online education can’t deliver outcomes equivalent to face-to-face instruction. They are split on whether investments in ed-tech have improved student outcomes. And they overwhelmingly believe textbooks and academic journals are becoming too expensive.

The findings also show faculty members are creating new opportunities with technology. Through experimentation with online education, for example, faculty members say they are able to serve a more diverse set of students and think more critically about how to engage students with course content, and with free and open course materials, they say they are increasing access to education.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2016 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Tuesday, Nov. 29, at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webinar to discuss the results of the survey. Register for the webinar here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology was made possible in part with support from Barnes & Noble College, Explorance, Knowlura, Mediasite by Sonic Foundry, and VitalSource.

Inside Higher Ed teamed with Gallup to hear from faculty members and academic technology administrators on these and other issues. The survey results are based on responses from instructors and administrators from all over higher education -- public, private and for-profit institutions, from two-year colleges to major research universities. The final sample of 1,671 faculty members and 69 administrators who oversee academic technology is therefore meant to create a representation of higher education as whole.

The free report can be downloaded here. Other highlights include:

- Fewer administrators and faculty members this year said technology in the classroom has led to significantly improved student outcomes, and more of them are having a harder time justifying investments in ed tech.

- Faculty members are conflicted about the scholarly publishing landscape. About half of surveyed instructors said they have more respect for research published in subscription journals than in open-access journals, but on the other hand, they strongly believe subscription journals are too expensive, for individuals and libraries alike. They are also concerned about adequate compensation for authors and peer reviewers.

- Both administrators and faculty members believe colleges are taking appropriate steps to protect personal information and intellectual property from cyberattacks. Few believe those security measures infringe on their privacy.

- Even in this unusually polarized election year (or perhaps because of it), most faculty members aren’t taking to social media to talk politics. In fact, most faculty members don’t even talk about their scholarship on social media.

Data Disillusionment

Colleges collect troves of data. When students log in to their learning management system, when they earn a grade in a course and when they check in with their adviser, each event creates a data point. By connecting that data to other information gathered about students, colleges hope to become more informed about where they are excelling and where they are falling short. And beyond using the data for evaluating the past, colleges are building data models for the future, for example by being able to flag when students are headed down a path that could lead to them missing an intended graduation date or dropping out.

This year’s survey asked administrators and faculty members to consider the efficacy of data-driven assessment efforts. The responses suggest a sense of disillusionment among administrators and faculty members about whom those efforts are meant to benefit.

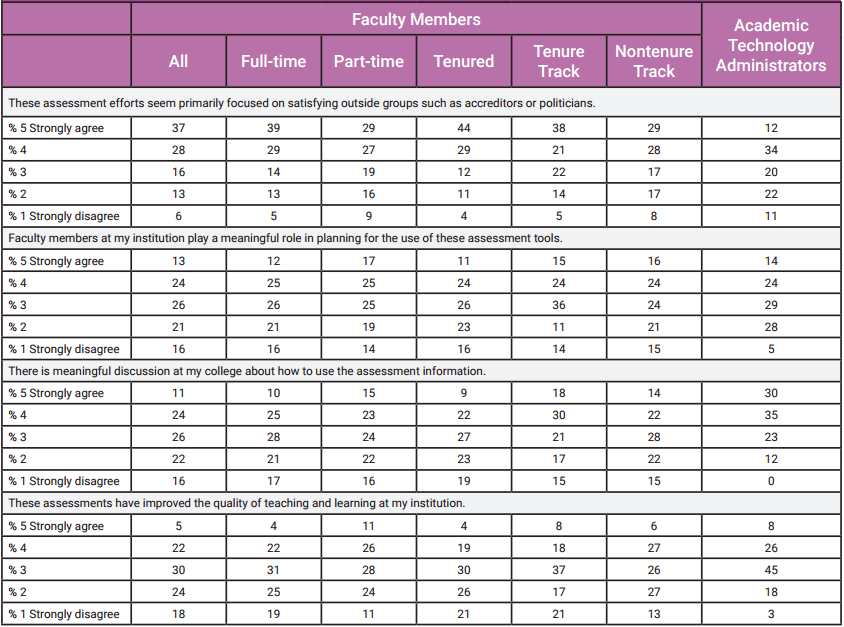

Only about one-quarter of faculty members (27 percent) and one-third (34 percent) of administrators said the efforts have improved the quality of teaching and learning at their institutions. Similar proportions of respondents said the same about the impact on degree completion rates. In comparison, nearly two-thirds of faculty members (65 percent) and about half of administrators (46 percent) said the efforts are meant to placate outside groups such as accreditors and politicians.

Faculty members’ responses to another question may explain why so few of them feel the assessment efforts are having a measurable impact. More than half of the instructors surveyed (54 percent) said they don’t receive data gathered by their colleges meant to help them improve their teaching. Only 24 percent said they do.

The responses also revealed that many respondents feel faculty members aren’t being properly included when colleges plan how they will use the assessment tools. Only 37 percent of faculty members, backed by 38 percent of administrators, said they play a meaningful role in those conversations. The remaining respondents either disagreed or said they weren’t sure.

Administrators and faculty members didn’t agree on everything, however. Most administrators (75 percent) said meaningful discussions are taking place at their colleges about how assessment data should be used, but a plurality of faculty members (38 percent) disagreed. None of the administrators surveyed disagreed strongly.

Ed Venit, a senior director at the Education Advisory Board, a research and consulting firm based in Washington, said the results are an example of that all-too-familiar dynamic between administrators and faculty members.

“Once again you have these two groups that don’t seem to be on the same page,” Venit said in an interview.

The issue isn’t simply that administrators and faculty members aren’t communicating with one another, Venit said, adding, “It’s an ownership issue.”

The EAB runs the Student Success Collaborative, a membership organization for colleges and universities using data-assisted research to improve student support, retention and graduation rates. Venit said the best examples of institutions that have closed the gap between administrators and faculty members are colleges that have recruited the expertise available on campus -- statisticians, social scientists and others -- both to determine how data should be used for assessment purposes and to evaluate the efforts.

“It enfranchises them,” Venit said. “It brings them into the fold.”

Publishing: Compensation, Price and Respect

The proliferation of open-access journals -- publications that don’t charge a subscription fee -- has increased the diversity of the scholarly communications landscape and given researchers new outlets to publish their work. Not all of the growth has been beneficial to scholars, however. Open-access publishing has also enabled “predatory” journals, which scam authors out of publication fees while offering them little in the sense of peer review or prestige.

Predatory publication has increased dramatically in the last five years, according to a recent study. This fall, the Federal Trade Commission began cracking down on publishers that mislead authors.

This year’s survey included a new section on scholarly communication that explored faculty members’ views on publishing and their interactions with journals, including whether where an article is published affects their opinion about the work.

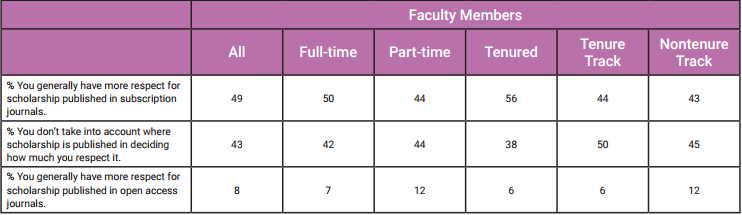

Over all, faculty members are divided on the question: they either say they have more respect for scholarship published in subscription journals (49 percent) or that it doesn’t matter where the research is published (48 percent). The gap was at its widest among tenured faculty members, 56 percent of whom said they favored research published in subscription journals. Very few faculty members said they have more respect for scholarship published in open-access journals (8 percent).

Heather Joseph, executive director of the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, a group in favor of open access, said she wasn’t surprised that faculty members said they have more respect for scholarship published in journals with subscription fees. Not only do those journals benefit from having been around much longer than open-access journals, she said, but they are also closely tied to higher education’s traditional incentive structures.

“Higher education institutions and the research enterprise as whole typically emphasize publication in subscription access journals in the research evaluation, promotion and tenure process,” Joseph said in an email. “If a faculty member is more likely to be rewarded for publishing in a subscription access journal, I would think their level of respect for those titles can’t help but be affected.”

But if open-access journals have a respect issue, subscription journals have a price issue. Faculty members said journal prices are “prohibitively high,” both for individual subscribers (82 percent) and academic libraries (70 percent). The survey did not ask faculty members if they believe the publication fees charged by open-access journals are too high.

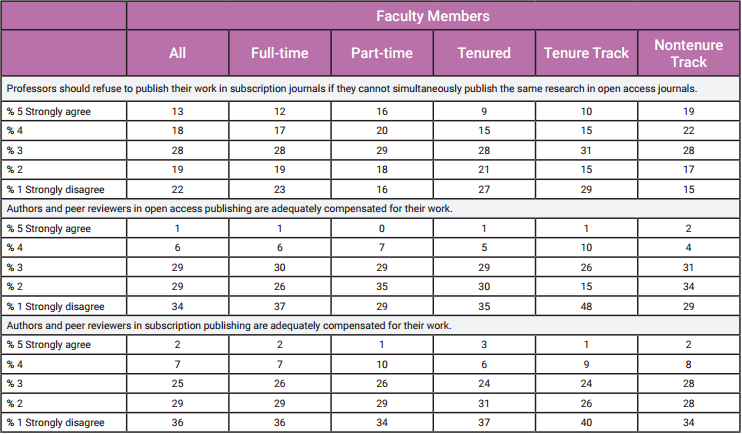

Whatever qualms faculty members have with subscription journals are not enough for them to support the idea of a boycott, though. About one-third of respondents (31 percent) said professors should refuse to publish an article in a traditional journal unless they were simultaneously able to publish the article in an open-access journal. Tenured faculty members were especially opposed to the idea, with 48 percent of respondents opposing it.

Faculty members also signaled their dissatisfaction with how authors and peer reviewers are compensated for their work. About two-thirds of respondents said journals don’t provide adequate compensation (65 percent for subscription journals, 63 percent for open-access journals), while those saying they do numbered in the single percentage points.

That finding points to a “systemic issue” that cuts across all journals, no matter which business model they follow, Joseph said. “It begs the question of revisiting the incentives that faculty are given by [higher education] and research institutions; perhaps at least discussing the notion of faculty being credited for their peer review work in the promotion and tenure process is an idea whose time may finally have arrived.”

Beyond publishing, the question of whether to use social media for scholarly purposes continues to divide faculty members. Like last year, a plurality of respondents (42 percent) said social media isn’t a good way for professors to communicate with the public, and about two-thirds of them (63 percent) are concerned about attacks on scholars who are active on Facebook, Twitter and other platforms.

Most faculty members (70 percent) said they are staying away from social media altogether, though some use it to express their views on their scholarship and teaching (10 percent), politics (5 percent) or both (15 percent).

Cybersecurity Confidence

This year alone, the personal information of hundreds of thousands of university employees has been exposed as college after college -- the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Central Florida; and Rowan University, to name a few -- has experienced cybersecurity breaches or malicious attacks.

The cases themselves are varied. In some examples, a university employee may have placed files in the wrong folder or clicked on a link in an email and unwittingly handed a hacker his or her login username and password. Some colleges have seen their systems infected with ransomware, malicious software that threatens to delete information unless the target pays to remove it. Some universities have even been infiltrated by rogue actors -- in some cases backed by foreign governments -- who have stolen intellectual property.

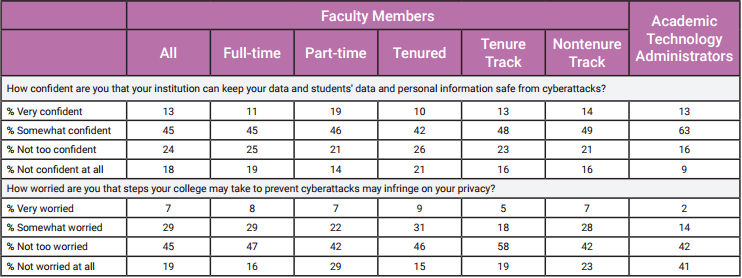

Administrators and faculty members aren’t terribly concerned by those threats, the survey results show. Most administrators (76 percent) and a slight majority of faculty members (58 percent) said they are confident their colleges are doing enough to ward off cyberattacks and protect sensitive information.

Cybersecurity experts said they were concerned by the responses. Bret Brasso, a vice president at the cybersecurity firm FireEye, said they suggest higher education, like other sectors, is taking the threats facing them too lightly.

“The traditional types of controls that many universities employ -- things like firewalls -- are very easily defeated by highly sophisticated adversaries that have the full backing of a nation-state behind them,” Brasso said in an interview. “How can higher ed institutions ever hope to defend themselves against a nation-state? The answer is they can’t.”

The survey also asked administrators and faculty members whether they believe cybersecurity measures infringe on their privacy, a question inspired by a discovery this past winter that the University of California System was secretly monitoring the activity on its network. Some faculty members in the system called the monitoring a “serious violation of shared governance and a serious threat to … academic freedoms,” though cybersecurity experts later said it is a commonly used tactic.

The privacy issue does not appear to be on most survey respondents’ minds. Nearly two-thirds of faculty members (64 percent) and more than four-fifths of administrators (83 percent) said they aren’t worried about sacrificing privacy for security.

Brasso called the finding “encouraging.” Hackers have typically exploited colleges’ commitment to academic freedom and openness, he said, but the responses show administrators and faculty members may be taking a more pragmatic approach to cybersecurity.

“There just has to be a balance,” Brasso said. “Bad guys are in some cases counting on complacencies or whatever nuances are inhibiting an organization from taking the proper safeguards to protect their assets.”

Impressions of Online Education

Faculty members surveyed for previous editions of this report have traditionally been overwhelmingly skeptical about the ability of for-credit online courses to produce outcomes equivalent to face-to-face education. This year’s sample is no different: a majority of faculty members (52-60 percent) said student outcomes from online courses are worse, even if they were in charge of teaching the courses themselves.

And like last year, faculty members who have taught online disagree. About half of them (47 percent) say online courses can be just as good as face-to-face courses. (The proportion of respondents who said they had taught an online course rose markedly this year, to 39 percent, up from 32 percent last year and 33 percent in 2014.)

Yet faculty members who have taught online share some concerns with those that don’t -- especially when it comes to student interaction. In response to questions that dig into specific features such as grading assignments and communicating with students, a majority of faculty members with online teaching experience said it is more difficult to interact with students outside of class, reach at-risk students and maintain academic integrity in online courses than in face-to-face courses. Those findings were also virtually unchanged from last year.

Justifying Ed-Tech Investments and Other Selected Findings

Unlike last year, however, administrators and faculty members aren’t as certain that investments in and use of educational technology in the classroom have led to significantly improved student outcomes. Last year, the first time these questions were asked, faculty members said by a roughly two-to-one margin that gains in student outcomes justified colleges’ spending on ed tech. This year, faculty members are more evenly divided: 57 percent said yes, 43 percent no.

A majority of faculty members (70 percent) still believe technology in the classroom has led to improved student outcomes, but most of them describe the gains as slight rather than significant. Still, the proportion of faculty members who said ed tech hasn’t improved student outcomes at all this year ticked up a few percentage points, rising to 30 percent from 25 percent last year.

The decline is more pronounced among administrators. They, like faculty members, also believe ed tech has improved student outcomes (87 percent gave that response), but far fewer of them this year said the gains have been significant (15 percent this year, 35 percent last year). However, it should be pointed out that with such a small sample of administrators, larger swings are to be expected.

- Faculty members generally give high marks to their colleges when it comes to technical support, but they are less impressed by other kinds of institutional support for online learning. Just about half of respondents said colleges provide adequate support for creating (49 percent) and teaching online (47 percent), and a plurality (40 percent) said they are fairly compensated for that work. When it comes to providing incentives to encourage instructors to teach online or acknowledging the time demands for those who do, a majority of faculty members said their colleges can do better.

- Most faculty members who have taught online courses, 79 percent, say the experience has helped them develop skills and practices that have improved their teaching in the classroom as well as online. Eighty-six percent say they think more critically about how to engage students with content. Eighty percent also say they make better use of multimedia content, and 76 percent say they better use their learning management system.