You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Super Age: Decoding Our Demographic Destiny by Bradley Schurman

The Super Age: Decoding Our Demographic Destiny by Bradley Schurman

Published in January 2022

As a social demographer (nonpracticing), I’m hardwired to vibe with The Super Age.

The aging of the U.S. population is the megatrend that all of us, including those of us in higher education, should be talking about.

We can mostly stop worrying about robots taking all the jobs or about colleges closing as precipitously as early-2000s Blockbuster stores. Instead, we should be worried—or at least thinking about—population aging.

The Super Age builds on the observation that the future belongs to the old. In the U.S., the 65-plus population is projected to climb from about 17 percent today to 21 percent in 2030. By 2050, the 65-plus population could make up a quarter of all Americans.

This trend matters a great deal to higher education. Near-term declines in the size of high school–age cohorts are already top of mind for most academic leaders. Still, today, the percentage of Americans age 18 and under (roughly 22 percent) is larger than the over-65 population. By 2035, those relative percentages will reverse, with those of traditional retirement age outnumbering the 18-and-under crowd.

The tipping point of when the old outnumber the young has already been reached in many countries. In Japan, almost three in 10 people are now elderly. By 2050, the proportion of elderly Japanese will increase to four in 10, while the ratio of young Japanese (0 to 14) to the entire population will fall to one in 10.

The author of The Super Age, Bradley Schurman, has given himself the professional label of “demographic futurist.” While I’m suspicious of anyone besides Bryan Alexander who describes themselves using the F word (Bryan is the real deal)—I have to hand it to Schurman for writing a terrific book in The Super Age.

Unlike most of us in higher ed who worry (I’d say legitimately) about a rapidly aging population, Schurman is mostly upbeat. While recognizing that there are reasons to worry about a growing older population—including worrying about low retirement savings with the demise of the pension system—Schurman is optimistic that an older society can be a good society. He argues that what is needed is a re-orientation of cultural assumptions and a redesign of workplace practices that are pro-aging and older-person friendly.

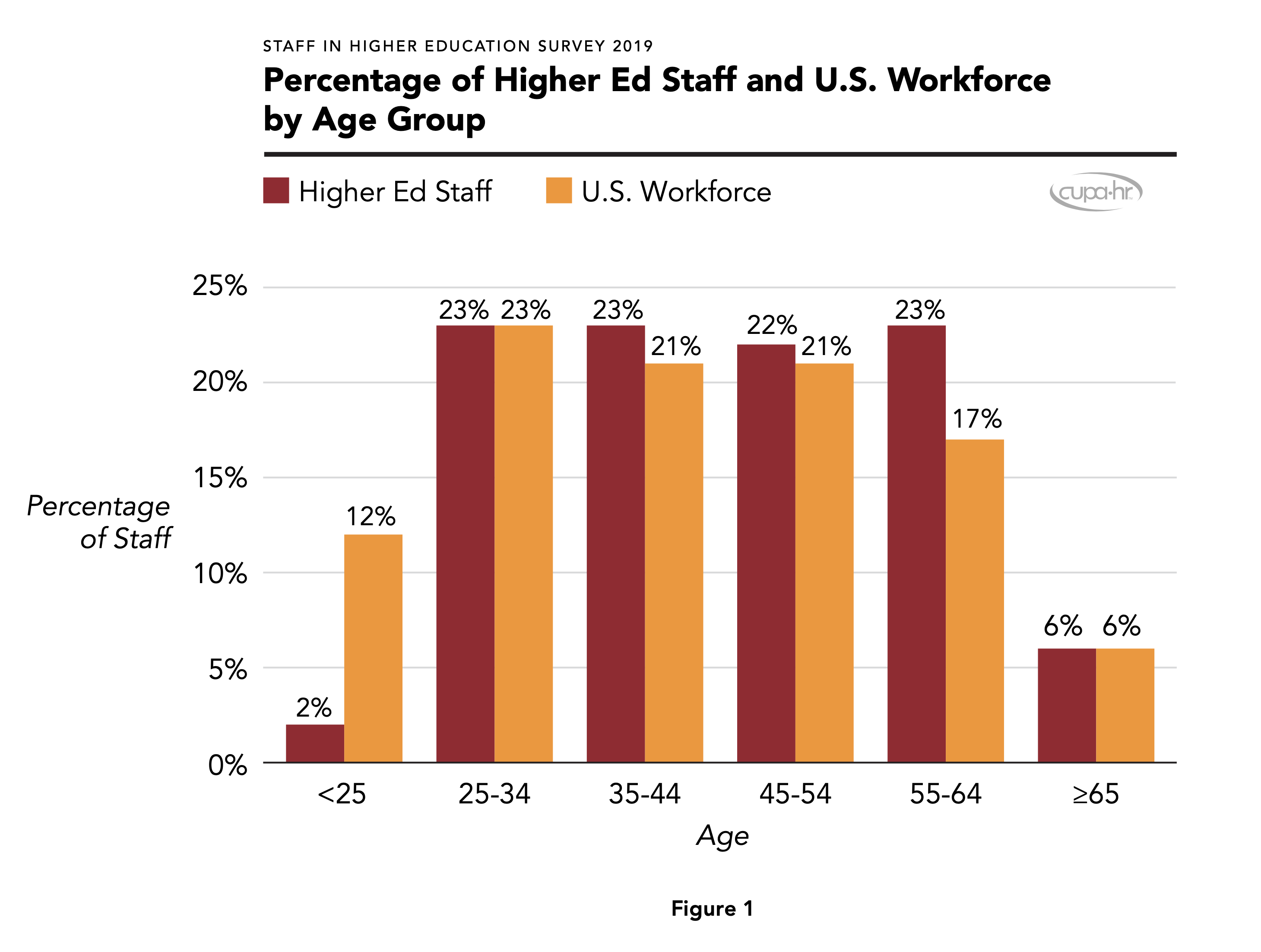

On the issue of aging and work, higher education is due for a rethink. The 2019 CUPA-HR report “The Challenges of an Aging Higher Ed Workforce” documents a higher ed staff that is already older than the U.S. workforce as a whole. Over half of all staff at colleges and universities are today 45 and older, compared to a quarter under age 35.

Nearly three in 10 (29 percent) of higher ed staff are 55 and over and are therefore either thinking about or actively planning for retirement. The pipeline for skilled nonfaculty academic leadership seems way too anemic in the face of these numbers. Who knows how many additional higher education professionals have chosen to step away from our campuses during the Great Resignation?

In The Super Age, Schurman argues that employers should be thinking about ways to attract and retain older workers. He argues that older workers are often the most productive workers but are too often given too little credit for their contributions. He wants to see more opportunities for older people to enter the labor force in quality part-time roles and more full-time jobs that allow flexibility to care for grandchildren or travel.

Colleges and universities may want to be especially aggressive in redesigning professional academic jobs that appeal to older workers. When an older higher ed employee leaves, decades of institutional knowledge and connections also walk out the door. Often, the key to getting things done in higher education is knowing how to navigate institutional structures that operate under principles that are imperfectly aligned with organization charts and published policies. Academia runs on relationships, and those with the deepest networks are our colleagues who have been around the longest.

We should figure out how to create desirable roles to bring back those who may have left during the Great Resignation and do much more to keep those one-third of our colleagues who may actively be thinking about postacademic life.

In an industry such as higher education that is aging even faster than the U.S. average, a book such as The Super Age might be just what we need to begin a conversation on planning for the future of an older academic workforce.

What are you reading?