You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Courtesy of Berklee College of Music

Berklee College of Music’s online program, priced at just over a third of tuition for the Massachusetts institution’s face-to-face degree offerings, raised eyebrows when it got off the ground in 2013. Conventional wisdom that online programs require more resources to produce had taken hold, and pricing models that favor online students were few and far between.

Five years later, Berklee remains an anomaly in higher ed, as most institutions continue to charge the same or more for online programs as for their face-to-face equivalents. Some arguments hinge on a philosophical belief that online education should be valued equivalently to face-to-face programs, while others emphasize the significant financial burden of designing and launching online courses from scratch.

In the face of a shifting landscape, Berklee has held firm. Online tuition for a bachelor's degree will go up half a percentage point this fall, from $1,479 per course ($59,160 for a 40-course degree program) to $1,497 per course ($59,880 total), but it still remains more than 60 percent less than face-to-face tuition -- $171,520. In the last few years, on-ground tuition has increased by a few thousand dollars while online tuition has stayed the same, widening the gap between the two even farther, according to Debbie Cavalier, Berklee’s senior vice president of online learning and continuing education.

More from “Inside Digital Learning”

State legislatures are looking for ways to reduce fees for students.

One institution has eliminated all student fees and textbook costs, absorbing them into online tuition.

A recent study offers insight into the return on investment for online programs.

As of fall 2017, Berklee Online's undergraduate enrollment stood at 1,138 students, up from 244 just two academic years earlier. Though Cavalier’s team had worried early on that the online program would cannibalize existing offerings, campus enrollment has instead increased from 4,490 undergraduates in 2013 to 4,532 in 2017, even as online has grown more popular.

“We’re of the mind that we’d rather cannibalize ourselves than run the risk of someone else doing that,” Cavalier said. “But whenever we entered into any kind of space online, whether it was nondegree, MOOCs, master’s, demand for our campus-based programs continues to grow and increase.”

The institution sees its online programs as a low-cost, flexible alternative for students who can’t or don’t want to commit the resources to a full-fledged residential experience. A handful of students who have come close to leaving the face-to-face program because of financial difficulties or professional opportunities have been able to transfer to the online format. Berklee hopes to formalize that pathway in the coming years -- “perhaps a semester online before attending in the fall, that kind of thing,” Cavalier said.

Berklee's president, Roger Brown, believes the institution has hit on a demographic that wants a music education but is willing to sacrifice the on-campus experience for a lower price.

"If we have an alternative that doesn’t require you to move to Boston and live in a fairly expensive city and allows you to get an education at a much lower cost, but an excellent education nonetheless, I think the demand is much greater," Brown said.

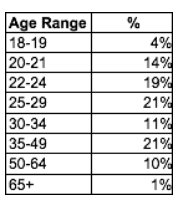

California is most represented among the home states of Berklee Online students, with 17 percent, followed by Texas with 7 percent and Florida, Massachusetts and New York with 5 percent each, according to data provided by the institution. Transfer students make up 66 percent of the Berklee Online population, according to Rachael Denison, manager of strategic research for marketing and recruitment for Berklee Online. This list provided by Denison illustrates the online program's diverse population.

The online program has attracted several distinct groups that wouldn’t have enrolled in a face-to-face program, according to Cavalier. Aside from federal financial aid requirements, students can complete their online degree at their own pace. Some students who dropped out as many as 40 years ago have resumed their degree programs in the online format, Cavalier said.

- Professional musicians looking to beef up their skills. Notable alumni include Stefan Lessard, bassist for the Dave Matthews Band, and Fraser T. Smith, a keyboardist who produced and co-wrote Adele’s “Set Fire to the Rain.”

- Entrepreneurs, like Jim Kerr of Orbitz and Walgreens, looking to indulge their latent music passions as a side pursuit.

- Military students nearing completion of their duties and looking for a new career path. “This is the best part of their week,” Cavalier said of their online classes.

- Teachers and professional musicians who have had successful careers and even won Grammy awards, but who eventually realize they don’t have the degree qualifications to shift to teaching in higher education. “A lot of people who are known for one thing are taking courses with us to bone up on areas they’re not well versed in,” Cavalier said.

Though some observers would assume the program’s quality must be lower than that of the face-to-face program, Cavalier insists that’s not the case, thanks to a homegrown learning management system, a robust student success and advising team, and a highly qualified stable of instructors.

Brown says the gap in cost between face-to-face and online at the institution is much larger than the gap in quality between the two modalities -- though online programs do sacrifice certain features.

"I think there’s no way around the fact that when you study online, you don’t get the same physical resources, you don’t get to be in a classroom with your classmates," Brown said. "If I were an online student I’d say, why am I paying for that?"

Making It Work

Berklee Online's administrative setup affords flexibility to experiment in ways that can filter out to the entire institution. Its application process, marketing automation and online learning platform have all been adopted on Berklee's physical campus.

“Even though we’re priced very affordably, we run a very efficient business and our costs are really in check with course development,” Cavalier said.

How does Berklee accomplish this feat when so many other institutions don’t even come close? Cavalier credits the massive reduction in cost that comes with not having to furnish recording studios, ensemble rooms and other high-maintenance buildings, particularly in the ritzy Back Bay neighborhood of Boston where Berklee’s campus is located. Physical spaces represent a quarter of the cost of producing a face-to-face program, according to Brown. Student activities and in-person advising and counseling centers also drive up on-campus program costs, Brown said. The institution doesn't save money by hiring adjuncts for online courses, as its online programs are led by Berklee's on-campus faculty.

How does Berklee accomplish this feat when so many other institutions don’t even come close? Cavalier credits the massive reduction in cost that comes with not having to furnish recording studios, ensemble rooms and other high-maintenance buildings, particularly in the ritzy Back Bay neighborhood of Boston where Berklee’s campus is located. Physical spaces represent a quarter of the cost of producing a face-to-face program, according to Brown. Student activities and in-person advising and counseling centers also drive up on-campus program costs, Brown said. The institution doesn't save money by hiring adjuncts for online courses, as its online programs are led by Berklee's on-campus faculty.

Each 12-week online course at Berklee costs between $80,000 and $100,000 to produce, according to Brown. He sees that expenditure as modest compared with what some other institutions pay for MOOCs, which can cost upward of $250,000.

The institution invested $8 million when launching its online programs and lost money for the first several years, according to Brown. He credits the turnaround to an increasingly efficient course development process that emphasizes “planning well, knowing what you want to do, shooting [videos] you need and not having to do a lot of work and then redo the work.”

“You can spend a whole lot of money if you're not well organized and don’t know what you’re doing,” Brown said.

All of the institution’s materials are hosted with Amazon’s cloud services, and the college hasn’t entered into revenue-share agreements with any for-profit companies, Cavalier said.

Berklee sees competition coming from “upstream” (courses and certificates at rival institutions) and “downstream” (MasterClass.com, subscription-service courses). The latter is currently more contentious, according to Cavalier. She believes Berklee’s for-credit courses are more appealing for students than more informal options.

“When you move upstream to degree programs online, we’ve been pretty deliberate to develop majors where there’s little to no competition but really strong market demand: songwriting, production, guitar,” Cavalier said.

View from the Outside

Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, thinks the institution has based its pricing model on marginal costs of the program (adding a certain number of online students to its existing operations) rather than average cost, which would add up all of the resources used by students and divide by the number of students.

"I expect the cost would be much higher if they were not able to piggyback on their existing infrastructure," Seaman said.

Cavalier said she and her team got advice on launching successful online programs from the UPCEA network, Southern New Hampshire University and Drexel University. The latter recommended Berklee switch to using Salesforce for all student-facing communication, including advising, technical support and the finance office.

“It just makes for a more streamlined experience so they can focus more on their education,” Cavalier said.

Susan Aldridge, senior vice president for online learning at Drexel University and president of Drexel University Online, advised Berklee to stay focused on its niche market, where it would face far less price competition than with disciplines that are more widely available online. Rather than creating a program based on faculty interest, Berklee stayed true to its core mission and simultaneously expanded its audience, Aldridge said.

Paul LeBlanc, president of Southern New Hampshire University, said the key to Berklee's success was its focus on the "job to be done" -- what students hope to accomplish in the program.

"A lot of schools are getting into the online market now," LeBlanc said. "The smart ones will look closely at Berklee’s good work."