You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

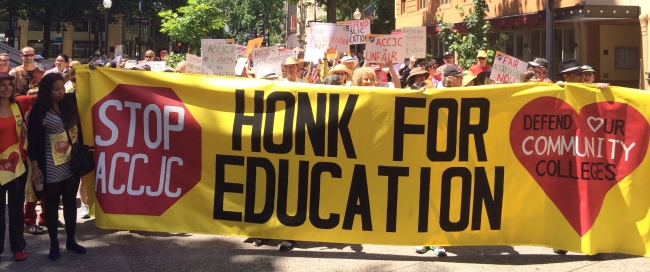

Protest of accreditor in Sacramento in 2014

AFT Local 2121

An uprising has been taking place in California.

The state’s 113 community colleges are breaking with their accreditor in an effort to reform the system of checks and balances that determines the institutions' quality.

This summer the two-year system will begin formally pushing away from the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges while also attempting to change that agency. This push is due to a number of reasons, ranging from the poor relationship and animosity between ACCJC and its member colleges to the need for the community colleges to have an accreditor that isn’t limited to overseeing two-year institutions.

“It is really, extremely complicated when you think about 113 of our institutions and upwards of 150 institutions altogether in ACCJC. Change is not something you can do with the flip of a light switch,” Brice Harris, the system's chancellor, said in an interview.

Harris and a system-convened task force have recommended that the colleges find a new accreditor. This month the system's board will decide whether or not to follow that recommendation, as well as how to make the move.

Yet instead of jettisoning the agency completely, some within the state are discussing how to change the ACCJC's leadership, at least as a temporary fix until the colleges transition to a new agency. For example, the task force recommended that the chancellor’s office enter a new agreement with a regional accreditor, but also operate under new ACCJC leadership.

“For ACCJC to fill the role of transitional accreditor, given the current uncertainties at the state and federal level, it must operate under new leadership with specific and significant structural and operational changes and use the authority of a special administrator or administrators to provide ongoing collaboration between ACCJC and the chancellor’s office,” said the task force report.

ACCJC President Barbara Beno has been a controversial figure among some of the state's community colleges, and there are some people who think getting rid of her or changing ACCJC's board could alleviate the problems.

“It’s appropriate to put on the table moving to a new accrediting body, however, we shouldn’t take off the table the option and opportunity to try and improve the current commission,” said Eloy Oakley, superintendent and president of Long Beach City College. “It seems easier and more rational to try and improve the current system rather than to completely throw it out and start over again. You just never know what you’re going to get, and no one is certain there is an accrediting body willing to take on 113 community colleges.”

The view that ACCJC has been unfair to some California colleges in its evaluations was upheld as recently as last month when the Obama administration rejected ACCJC’s appeal of two of the U.S. Department of Education’s 2014 findings against the accreditor. Education Secretary John King confirmed the department's view that ACCJC is not widely accepted by educators and doesn't assign enough academics to evaluation teams. ACCJC has until January 2017 to resolve the department’s findings.

But reforming the agency from the inside also may be easier said than done.

“What we have found and what the task force has found at the same time is that, bottom line, the culture of ACCJC is so toxic that it’s not really possible to transform internally and it’s not clear, short of replacing everybody, that that toxic culture would change,” said Fred Glass, communications director for the California Federation of Teachers, a union representing many faculty members at the California colleges.

For more than a decade the system, college leaders and faculty groups have called for the ACCJC to improve its relationship with colleges, but nothing has changed, Glass said.

“This needs to be a culture of collaborative improvement rather than compulsory compliance and there needs to be a positive working relationship between ACCJC and the colleges,” he said, “not the harsh, punitive relationship that has existed now for over a decade.”

Tensions between the colleges and ACCJC came to a head in 2013, when the agency sought to revoke the accreditation of City College of San Francisco. That move led to a number of lawsuits and complaints from the state's faculty unions, political leaders and the Education Department.

Still, Oakley said some within the system are urging caution as the move away from ACCJC picks up steam.

"Our faculty representatives have been very vocal about their dissatisfaction with the current system and I understand and empathize with their concerns," he said. "However, the commission and accrediting system serves more than just one constituent group, and we have to look at it from all angles."

The situation creates an interesting dilemma for the colleges -- and the system. On one hand, the system is clearly pushing away from the accreditor and working through the process of finding a new one. Yet at the same time it must continue working with ACCJC in order to maintain the accreditation status of its colleges.

Although no one has done this before, at least on this scale, there is a way for the colleges to remain accredited through ACCJC and to transition away from the agency as they each go through their periodic reaccreditations, Glass said. “It will take time … it’s never been about getting out of accreditation, it’s been about re-establishing a fair accreditation process.”

Glass said he’s optimistic that, under the transition, college site review teams will feel more incentive to take ownership of the accreditation process and see that it is carried out in a stable, efficient and credible manner.

“We’re all nervous about how it’s going to move forward because it hasn’t been done before, but we do know one thing and that is we cannot continue with the accreditation regime that we’ve had. That’s become clear to everybody,” Glass said.

The Push for Four-Year Degrees

Although animosity between ACCJC and the California institutions appears to have been the impetus behind the break, some say the system's decision to embrace an identity beyond the traditional two-year degree is a key factor.

The discussion has shifted far beyond just fixing ACCJC, said David Morse, president of the Academic Senate for California Community Colleges and an English professor at Long Beach City College. “The more recent focus of the conversations has been on the benefits of aligning our accreditation structure with that of the four-year institutions.”

The community college system has spent the past few years developing its transfer agreements with the California State University and University of California systems. A handful of the colleges also began offering their own bachelor's degree programs. ACCJC is a two-year accreditor, according to its recognition status with the Education Department. But in 2014, the agency earned permission to approve bachelor's degrees on a limited basis. But the ongoing problems between the colleges and ACCJC led to the agency losing that authority.

“The simple fact is that students have always moved back and forth among the segments of higher education in California, so we have begun to question whether a separate accreditor for the community college system makes sense,” Morse said. “No other region of the country has this same division between two-year and four-year institutions, and the overall feeling is that our systems would all benefit from greater alignments of our accreditation structures.”

Changing the ACCJC's leadership or reforming its practices would accomplish that alignment of the state’s higher education systems, he said.

Constance Carroll, chancellor of the San Diego Community College District, said she’s in favor of one single accrediting commission that serves both the state’s two- and four-year institutions.

“This is especially important in view of the emergence of community college bachelor's degrees, specialized degrees for transfer and other developments that argue for a closer knowledge and collaboration among the segments of higher education,” she said.

But is there any guarantee that a new accrediting system will be better for the colleges than just fixing ACCJC?

“I don’t think it could be worse -- that’s why I think everyone involved is willing to make the leap into the void,” Glass said. “We’re very hopeful whoever ends up becoming the accreditor for California’s community colleges, it’ll work better.”

The Next Accreditor

The most likely suspect to receive the community college system could be the WASC Senior College and University Commission. WASC Senior is the regional accreditor for all of California’s four-year public universities.

“The reason we have ACCJC is because WASC Senior didn’t have the capacity to handle all of these two-year institutions, so unless a major change happens with WASC Senior in terms of capacity, I don’t see how it can take on 113 colleges,” Oakley said. “It’s a difficult task, and it takes a lot of manpower to keep up with the needs of the system.”

Under WASC Senior’s current department recognition, the accreditor couldn’t accept a community college applicant because the senior college commission is only for bachelor's degree-granting institutions, said Ralph Wolff, who formerly served as president of WASC Senior and now sits on the federal panel that advises the Education Department about accreditation, in a January interview with Inside Higher Ed.

WASC Senior would have to go before the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity in order to make that change, Wolff said.

But there are other options available to the colleges, he added. One would be to choose a national accreditor like the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools. But Wolff admits that national accreditors are not treated the same as regional ones and there’s no guarantee that they can embrace the 2.1 million students who attend California’s community colleges.

A third option would be the creation of a new, major accrediting agency. But that agency would be required to gain federal approval and go though an entire accrediting cycle for at least one or more institutions under the current regulations, he said.

Robert Shireman, a senior fellow with the Century Foundation and a former Education Department official, said creating a new accrediting agency would take the longest amount of time. And using an existing national accreditor would be a difficult move politically, he said, since many associate them with for-profit colleges.

“A fourth option is for the state of California to create its own accrediting body and get it recognized similar to the New York Board of Regents,” Wolff said. “But that would take many years and money.”

Wolff said he’s not certain there is even support for California to create its own agency.

One last option, Shireman said, would be for another regional accreditor besides WASC Senior to expand its geographic scope to include two-year degrees in California.

"The colleges could become subunits of Cal State campuses. Those campuses are already approved to offer certificates, so the community colleges could change their transfer degrees to transfer certificates," he said.

But Harris said it’s premature to look at how transitioning to a new accreditor would happen, since it will take anywhere from six to 10 years to make the transition.

“If WASC were to be the receiving accreditor, you’d be more than doubling their size. That’s not something you could do in a hurry,” Harris said, adding that looking at other accreditors would be an equally “gargantuan task” and he is not aware of conversations about how to make it happen. However, Belle Wheelan, president of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, another regional accreditor, recently spoke to the California colleges about the future of accreditation, he said.

A move to an existing accreditor also could increase the number of institutions involved, Harris said, since the opportunity to leave ACCJC would be extended to Hawaiian and Pacific Island institutions that currently are accredited by ACCJC.

Oakley said much of the debate depends on whether the Board of Governors and the new chancellor can strike a balance between repairing and removing ACCJC in a way that maintains the quality of the colleges’ accreditation status. Harris is retiring from the chancellor position in April.

Harris makes his recommendations to the Board of Governors this month. He expects that by July, the direction the colleges are heading will be much clearer.

"I don’t think ACCJC will go away tomorrow," Harris said. "They’re our accreditor and will be in the near term. There are changes we’d like to see take place in ACCJC to better serve our institutions."