You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

We still know surprisingly little about Ph.D. career pathways. So the Council of Graduate Schools’ data-collection effort on Ph.D. outcomes continues to yield valuable information. This time, the information is about recent jobs changes among Ph.D.s.

The council’s new research brief -- the fourth since it began releasing data on its Ph.D. Career Pathways project last year -- says that many Ph.D.s switch jobs in their early careers and even into midcareer. That could reflect postdoctoral training opportunities, the brief says, but it also “signals that earning a Ph.D. is just the beginning of one’s career, and job changes continue throughout the next 15 years in the workforce.”

In other words, according to the council, “a first job is certainly not the last job. This underscores the importance of preparing Ph.D. students not only for their first job searches but also for preparing them to navigate different job opportunities and careers as a whole.”

Some Ph.D.s move between academe and business, government and nonprofit work, and their career pathways are “not always linear, through a single employment sector.” Nor are they unidirectional, as some Ph.D.s move from outside academe to faculty and administrative positions. So Ph.D. programs should help prepare students to navigate job opportunities and understand the value of their degrees across across sectors.

There is “no singular pathway to faculty and administrative positions at colleges and universities, even if this fluidity is more pronounced in some fields than in others,” reads the council’s new brief, which divides Ph.D.s into cohorts: those who earned their doctorates three years ago (Cohort A), eight years ago (Cohort B) and 15 years ago (Cohort C). The council focused on job changes within the last three years to determine which cohorts were most job-mobile.

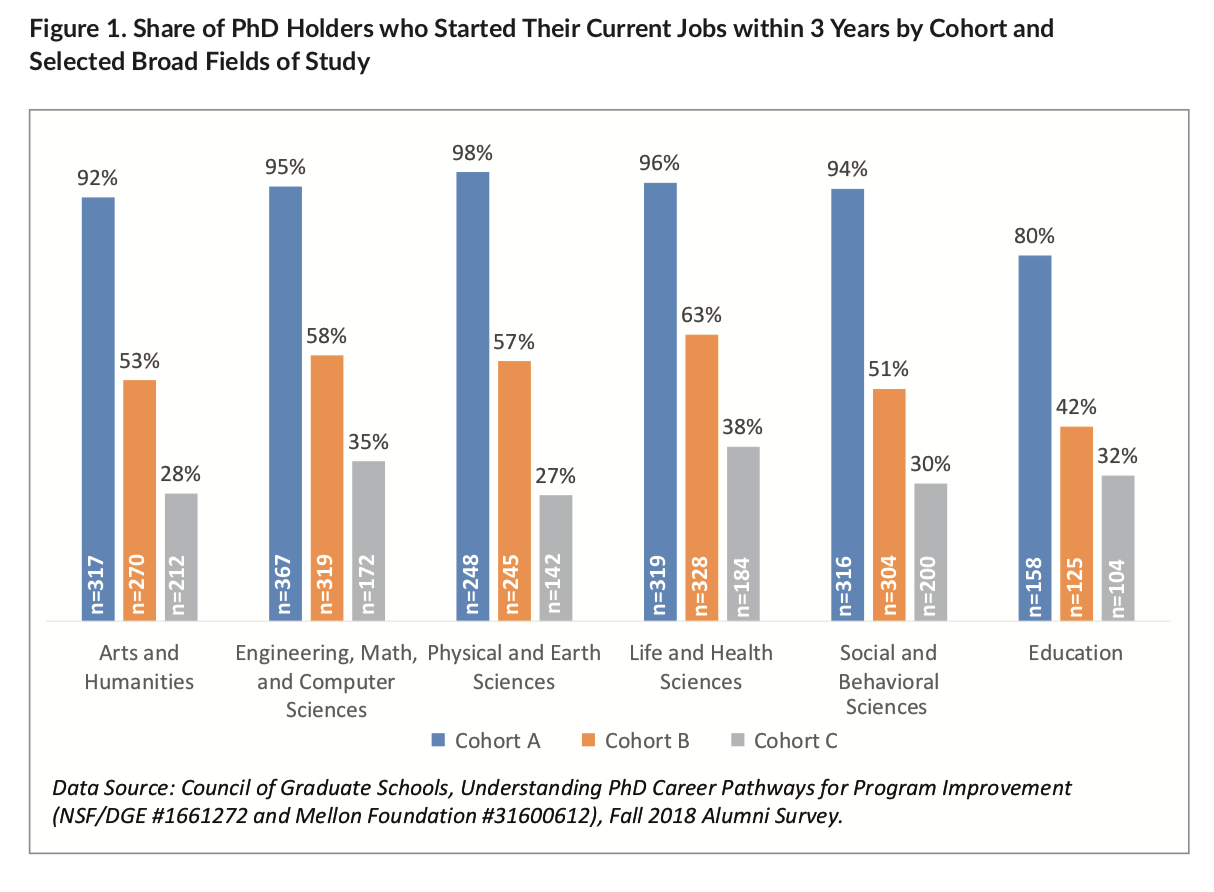

Unsurprisingly, almost all respondents who earned their Ph.D.s three years ago changed jobs within those last three years: in every broad field of study except education, over 90 percent of Ph.D.s indicated that they switched to their current jobs within the last three years. Education Ph.D.s in this cohort switched recently, too, just at a lower rate -- 80 percent (CGS assumes that more education Ph.D.s held jobs while pursuing their doctorates than the cohort as a whole).

Source: Council of Graduate Schools

Fewer Ph.D.s who graduated 15 years ago changed jobs recently. In every broad field except life and health sciences -- where there was more movement -- about one-third of these respondents said they changed jobs within the last three years. Most respondents moved to jobs within the same sector.

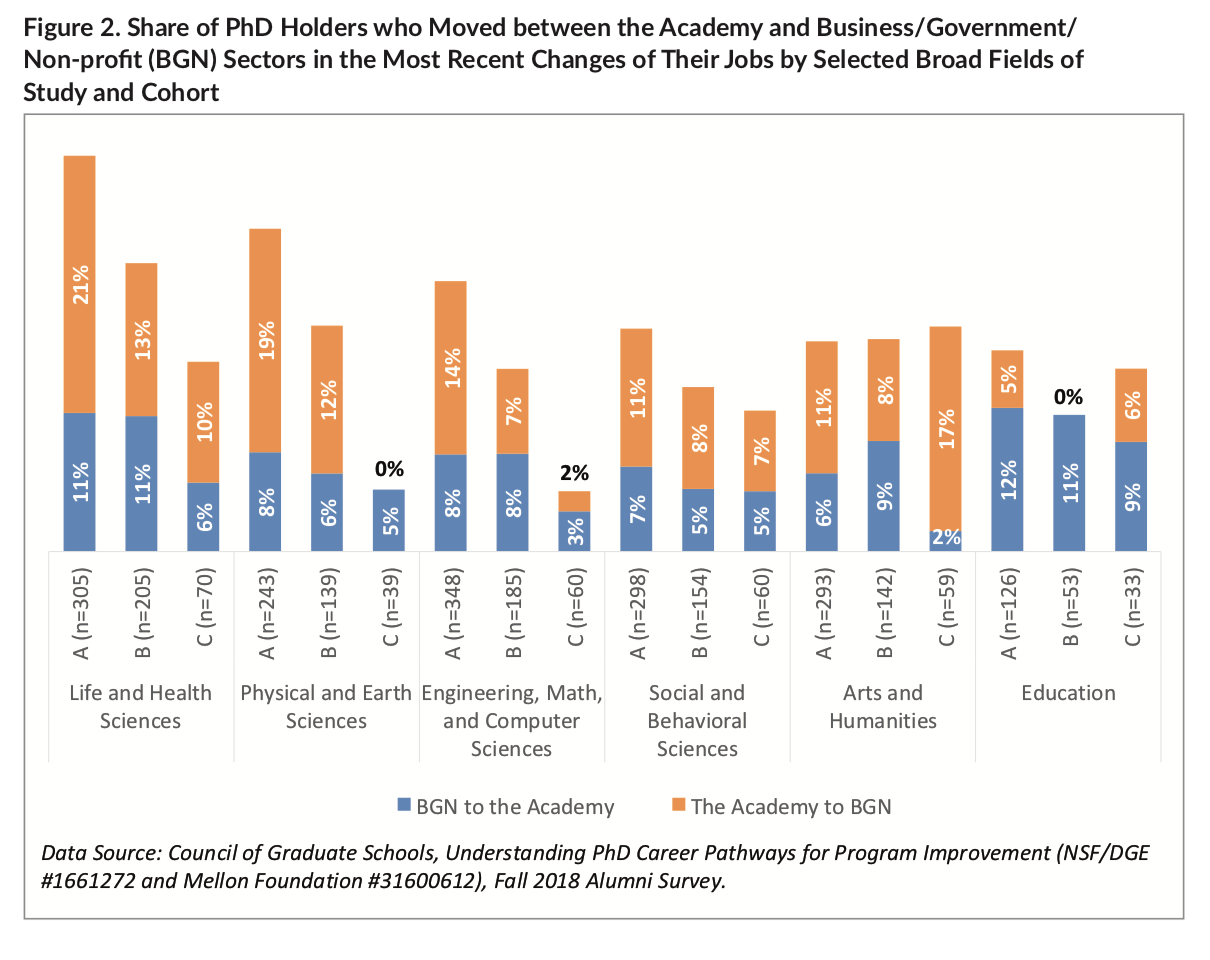

Over all, most intersector job changes among science, math, technology and engineering Ph.D.s occur in the three years after graduation. Thirty-two percent of life and health sciences Ph.D.s, 27 percent of physical and earth sciences Ph.D.s, and 22 percent of engineering, math and computer science Ph.D.s who graduated three years ago have moved between business, government and nonprofits and academe.

In the arts and humanities, movement across sectors within the last three years was consistent across all groups of graduates (three, eight and 15 years out), at 17 to 19 percent. The majority of all the moves happened in one direction: from academe to outside. The most moves to academe from other sectors happened for education Ph.D.s.

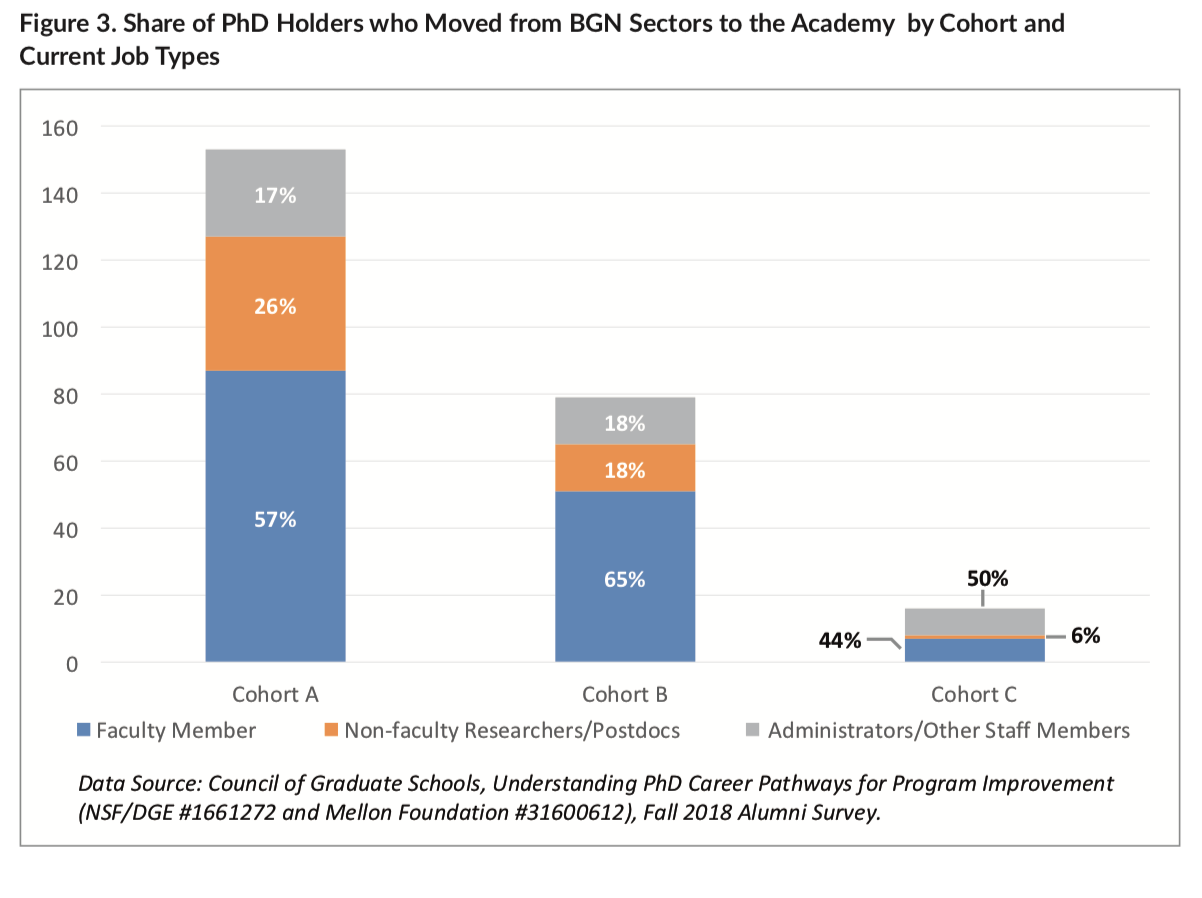

The majority of Ph.D.s in both the three- and eight-year cohorts who moved into academe moved into faculty positions. The 15-year cohort respondents were more likely to move into administrative jobs.

Data are based on the council’s Career Pathways Project Fall 2018 Alumni Survey. The questionnaire was sent to Ph.D.s three, eight and 15 years post-Ph.D. in selected programs at 51 institutions. Universities administered the survey and shared the results with the council, making for 4,766 respondents total.

The council’s brief includes “conversations starters” for Ph.D. programs, to “ensure that career diversity is seen and celebrated. Culture change happens incrementally and requires active participation of students, faculty and administrators.”

A good first step is understanding “how your campus community communicates about career options for Ph.D.s,” the council says. Some related questions for graduate school staff members and program directors and unit deans, among others, include, “What kind of professional development opportunities does your institution provide Ph.D. students to help them imagine and navigate into their second jobs and beyond?” and “What kind of resources and guidance does your institution offer to faculty members and advisers, so that they talk to their students about a range of job opportunities and career pathways for Ph.D. holders?”

Suzanne Ortega, president of the council, said Wednesday that Ph.D. career pathways “are less linear than is often supposed,” with movement across sectors among all alumni groups.

As for the Ph.D. Pathways project as a whole, Ortega said that more universities contributed data to this year’s survey than even last year’s, “and we continue to see a high level of interest” from member institutions.

Beyond graduate programs, professional organizations want more information about what Ph.D.s end up doing, for how long and where. Some have started their own data-collection efforts. The Association of American Universities also launched the Ph.D. Education Initiative, in part to promote data transparency on these issues.

Steven R. Smith, executive director of the American Political Science Association, said his organization has been spending a lot of time thinking about Ph.D. pathways. Currently, he said, the APSA has good data on job placements a year after Ph.D. completion. But it would like to investigate further and might apply for a grant to do so in the coming months. He called the council’s new brief “informative and timely,” especially “given the growth of contingent faculty and changes in the academic labor market for political scientists.”