You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A high school student collects her diploma at Bradley-Bourbonnais Community High School in Illinois in May. A new analysis sheds additional light on college enrollment among new high school graduates amid the pandemic.

KAMIL KRZACZYNSKI/Contributor/Getty Images

College-going rates among high school graduates declined across the board this fall, but far fewer graduates of low-income and high-poverty high schools, and of high schools with many Black and Hispanic students, enrolled in college during the pandemic, new data show.

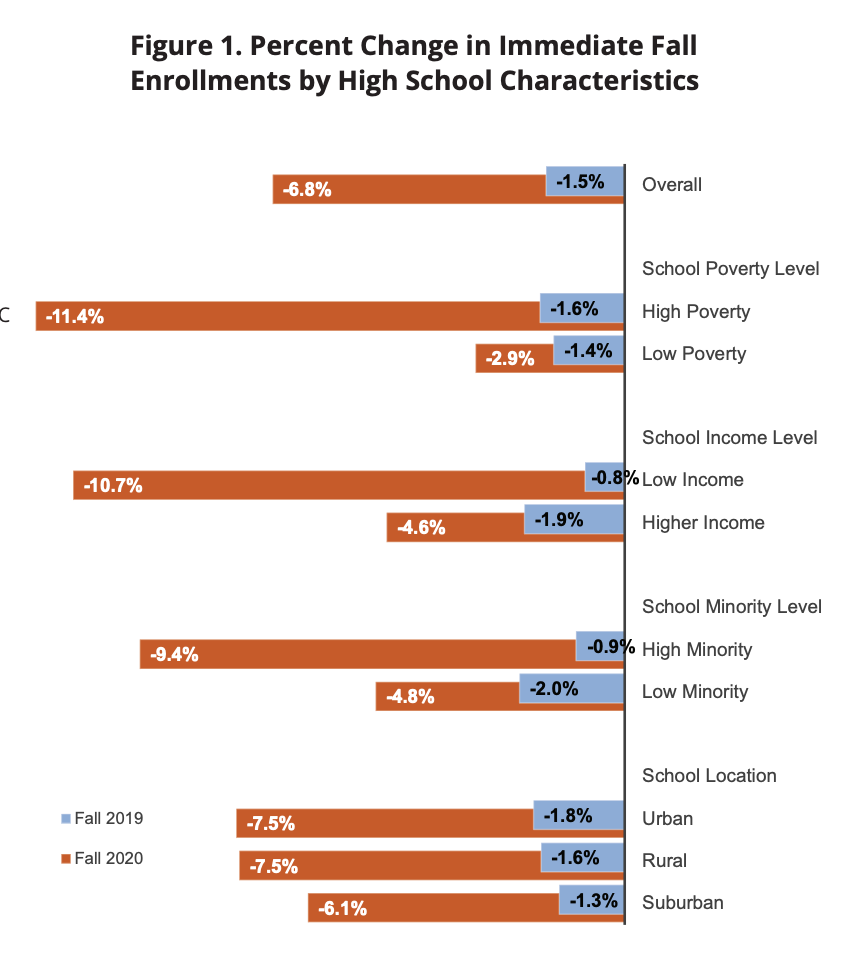

Immediate college enrollment fell by an unprecedented 6.8 percent this fall, compared with a 1.5 percent year-over-year decline in fall 2019, according to a new special analysis of the High School Benchmarks report from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. While a 6.8 percent decline is far better than an earlier estimate of 21.7 percent, it is still 4.5 times larger than the 2019, pre-pandemic rate.

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center puts together annual reports on high school graduates’ postsecondary enrollment, persistence and completion outcomes. It has also released several analyses of college enrollment amid the pandemic. The latest analysis updates preliminary results posed in December. It also corrects a process error that resulted in an overestimate of the rate of decline in college enrollment counts throughout the December report.

The new report includes data on 860,000 high school graduates from nearly 3,500 high schools who upon graduating enrolled at 87 percent of the institutions that participate in the Clearinghouse.

Before the pandemic, college-going rates among graduates of high-poverty and low-poverty high schools kept pace with each other, the research center report shows. The same is true for graduates of urban, rural and suburban high schools.

Before the pandemic, college-going rates among graduates of high-poverty and low-poverty high schools kept pace with each other, the research center report shows. The same is true for graduates of urban, rural and suburban high schools.

The pandemic blew those disparities wide-open. In the fall of 2020, the rate of decline in high-poverty high schools dropped at about four times the rate of the decline at low-poverty high schools -- by 11.4 percent and 2.9 percent, respectively.

Enrollment among graduates from low-income high schools declined by 10.7 percent this fall, compared with 4.6 percent for graduates of high-income high schools. The report defines low-income schools as high schools where at least 50 percent of students -- not just graduating seniors -- are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. These data break pre-pandemic patterns, when enrollment among graduates of high-income high schools fell more steeply year over year than enrollment among graduates of low-income high schools, by 1.9 percent and 0.8 percent, respectively.

At high-minority-enrollment high schools, the number of college enrollees declined year over year by 9.4 percent, compared with a 4.8 percent decline at low-minority-enrollment high schools. The report defines high-minority schools as high schools where at least 40 percent of the students are Black or Hispanic.

Immediate college enrollment among graduates of both urban and rural high schools each declined by 7.5 percent in fall 2020, compared with a 6.1 percent decline among graduates of suburban high schools, the report shows. The report uses the National Center for Education Statistics' urban-centric locale code to define urban, rural and suburban high schools.

Without some intervention, it’s unlikely that college enrollment rates will snap back to pre-pandemic patterns when the pandemic has ended, said Audrey Dow, senior vice president at the Campaign for College Opportunity, an organization working to improve college completion rates and expand access to higher education in California.

“The data is sobering,” Dow said about the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center analysis. “The most vulnerable students who have the most to gain from a college education are bearing the brunt of the pandemic effects. If the federal government, states, colleges and universities do not step up in intentional ways to support low-income students of color to enroll in and stay in college, we will see these disparities in college enrollment persist.”

The research center data only include information from participating colleges, but some state-level trends paint a similar picture of college enrollments.

The Class of 2020 at Hawaii’s public high schools achieved a record graduation rate, but fewer of them enrolled in college after graduating than did in the past, The Honolulu Star-Advertiser recently reported. Only half of graduates went straight to college after high school, compared to 55 percent the previous year. That 5 percent difference is the steepest year-over-year drop ever recorded in the state.

College-going rates among Hawaii’s high school graduates also varied based on ethnicity and socioeconomic factors. Just 35 percent of Native Hawaiians enrolled in college right after graduation -- a 44 percent drop compared with the Class of 2019. Only 29 percent of Pacific Islanders enrolled in college upon graduating, compared with 35 percent the year prior.

Experts expected this. Numerous reports have shown that low-income and minority students have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.

Additional financial aid will be essential in helping those students return to higher education, Dow said. She recently spoke in favor of a proposal to expand the Cal Grant -- California’s statewide financial aid program -- and is a strong advocate of doubling the federal Pell Grant.

“If we are going to curtail college enrollment disparities, a premium must be placed on financial aid; ensuring applying for aid is further simplified and that ALL students are supported to apply,” Dow wrote in an email. “The doubling of Pell will go a long way to giving students the economic peace of mind to choose college as well as the availability of emergency aid that states and colleges and universities can prioritize.”

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center analysis broke down college enrollment rates of decline by sector. As many other reports have also shown, community college enrollment was hit hardest by the pandemic. Immediate community college enrollment fell by 13.2 percent this fall, compared with a 1.3 percent enrollment increase the previous year. Immediate enrollment at public four-year colleges declined by 3 percent in fall 2020, compared to a decline of 2.6 percent in 2019. Enrollment at private, nonprofit four-year colleges fell by 5.2 percent in fall 2020 versus a 3.8 percent decline in fall 2019.

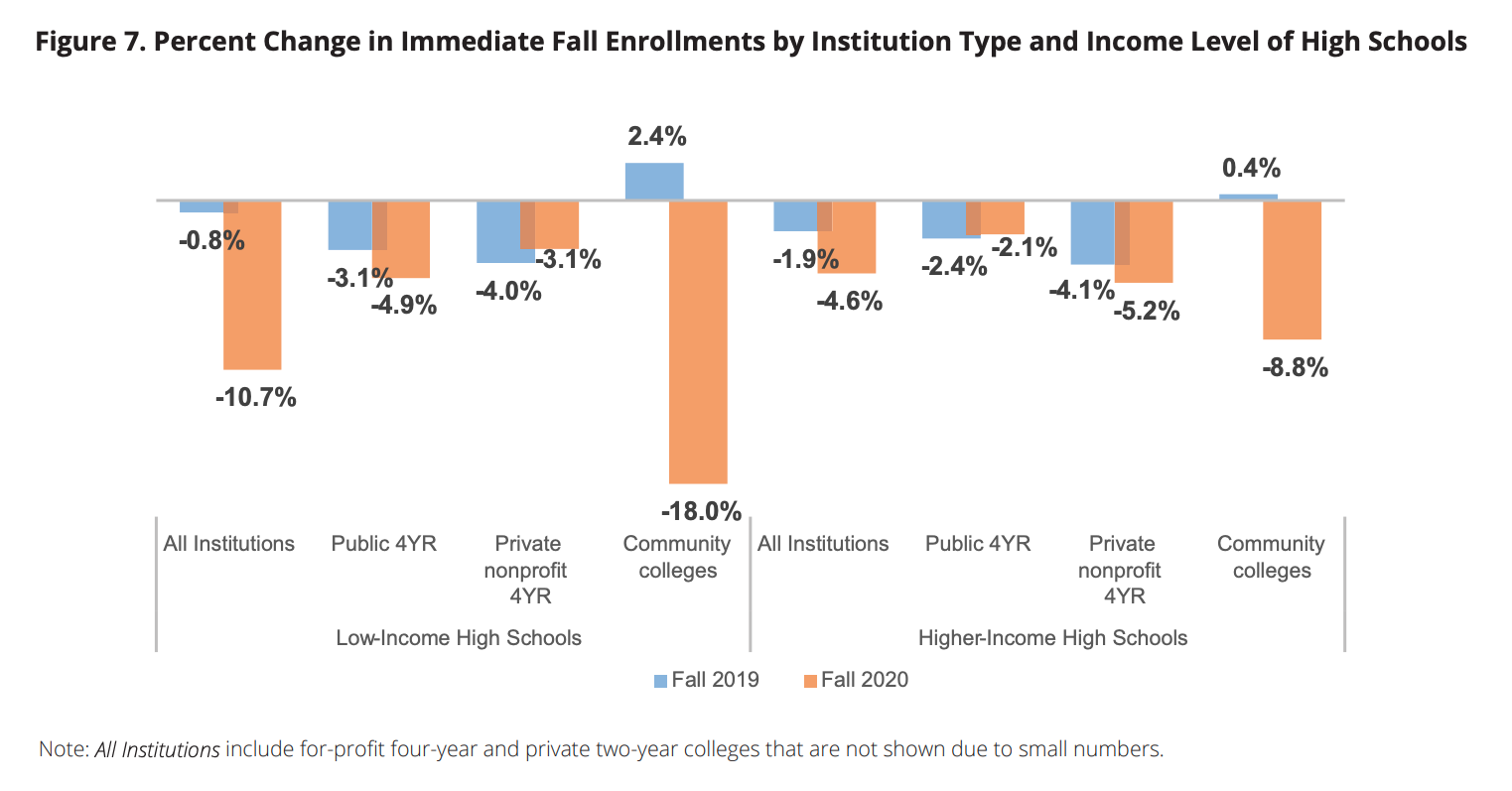

The report also goes a step further, breaking down sector-level declines by high school income level. Immediate enrollment at public, four-year colleges declined by 2.1 percent among graduates of high-income high schools and by 4.9 percent among graduates of low-income high schools in fall 2020. At private nonprofit four-year colleges, immediate enrollment numbers fell by 5.2 percent among graduates of high-income high schools this fall, and by 3.1 percent among graduates of low-income high schools.

Community college enrollment this fall revealed the largest differences between graduates of low-income and high-income high schools. Immediate community college enrollment among low-income high school graduates declined by 18 percent in fall 2020, compared with a 2.4 percent gain in fall 2019. Among high-income high school graduates, community college enrollment declined by 8.8 percent in fall 2020, compared with a 0.4 percent gain in fall 2019.