You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Tima Miroshnichenko/Pexels.com

The Association of American Colleges and Universities’ newest report, "How College Contributes to Workforce Success: Employer Views on What Matters Most," is something of a mixed bag for higher education.

First the good: employers generally have confidence in higher education and value the college degree. They believe that a liberal education -- or preparation for more than a specific job -- provides knowledge and skills that are important for career success. And increasingly, employers say, college graduates are more effective at explaining what they bring to the table.

Personal aptitudes and mind-sets also play a role in career success, employers say. Breadth and depth of learning are essential to longterm performance. Completion of active and applied learning experiences in college gives job applicants a clear advantage in the hiring process, as well.

Now the not-so-great findings: employers see room for improvement in how colleges and universities prepare students for work. Views on higher education and perceptions of recent graduates also vary significantly by employer age and educational attainment. Younger employers -- those under 40 -- place a higher value on civic-related learning outcomes and experiences than do employers over 50.

The AAC&U is a staunch proponent of liberal arts education and what it can do for individuals as well as society. But what does this particular set of findings mean, especially at a time when higher education, and society, are facing all manner of upheavals related to COVID-19?

‘The Bottom Line’

Ashely Finley, vice president for research and senior adviser at the AAC&U, and author of the report, said Monday that “the bottom line is that at a time when colleges and universities might be tempted to retrench resources, specifically to limit breadth of learning and skill development, they should not.”

Employers continue to find high value in students developing a “broad skill base that can be applied across a range of contexts,” Finley said. “Our results also point to how much fostering mind-sets -- like work ethic and persistence -- matter for workplace success,” as far as employers are concerned.

Not necessarily related to the pandemic, Finley also said that the consistent differences of opinion expressed by employers under 40 and those over 50 suggest that liberal arts-related skills and civic and community mindedness are becoming more important to employers, not less.

The AAC&U surveyed nearly 500 executives and hiring managers from businesses of varying size in October. Technology was the most represented sector, at 27 percent of respondents, following by banking or financial services (12 percent), manufacturing (9 percent), professional services (9 percent), health care and medicine (9 percent), construction (9 percent), and more. Most companies (72 percent) were private. They were roughly split between having local, regional, national and multinational profiles.

The AAC&U did ask employers about COVID-19 and how it’s changed their thinking and hiring preferences. But Finley said the answers were so mixed that they were essentially a “wash.” Those questions are therefore not reflected heavily in the report. Yet COVID-19 would certainly have been top of mind for respondents, given the timing of the survey. Other events, such as the 2020 presidential election, may have been, as well.

To that last point, the AAC&U found -- as have other recent surveys -- that higher education has a “public trust problem.” In 2018, for example, the report says, Gallup found that the percentage of American adults who had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education had dropped from 57 to 48 percent in just three years, a bigger drop than any other U.S. institution saw over the same period.

Interestingly, and by contrast, the AAC&U found that employer confidence in higher education remained relatively high in 2020, and had even improved since 2018: some 67 percent of employers had a great deal or a lot of confidence in higher education, compared to 63 percent two years earlier.

As for the college degree itself, which here includes a credential, 87 percent of employers said it is “definitely” or “probably” worth the investment of time and money. The percentage of those who believe it is “definitely” worth it actually rose seven points since 2018.

“At a time of great change in American higher education and in the global economy,” the report says, data strongly suggest that “a liberal education will pay off for students on the road ahead.”

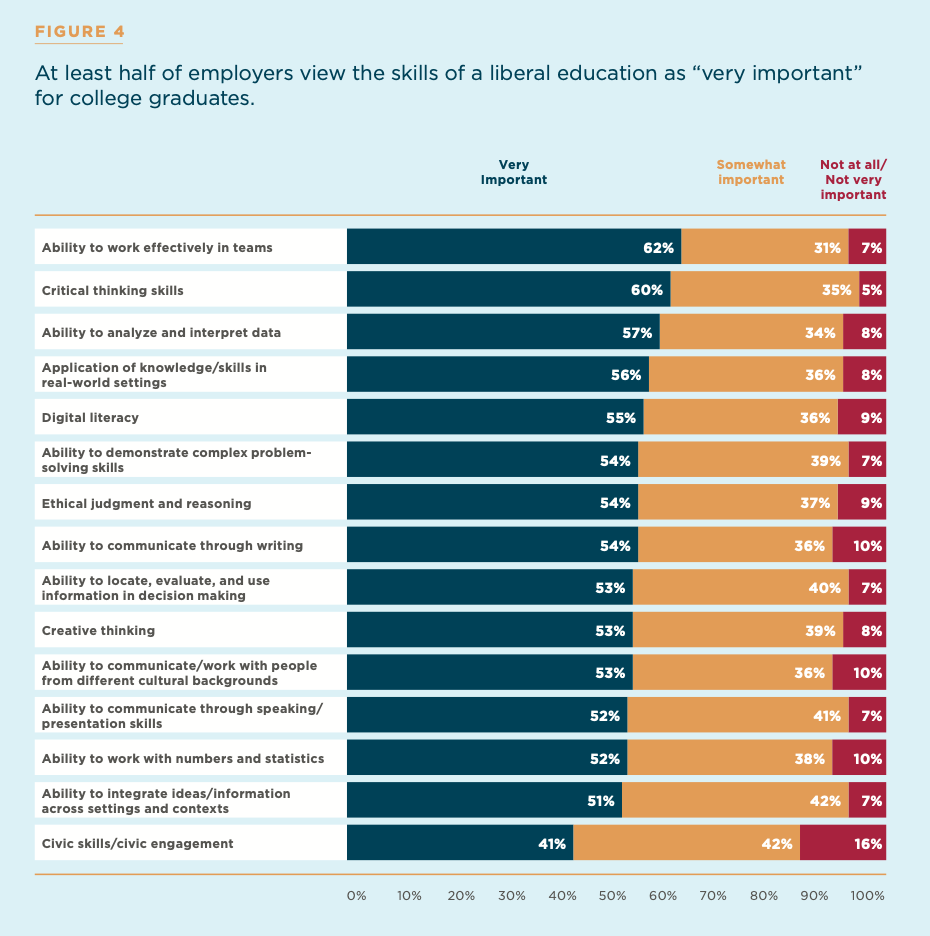

The AAC&U has long worked with employers to see which essential learning outcomes they value. Consistently top ranked are critical thinking and analysis, problem solving, teamwork, and communication through writing and speaking. Civic-oriented outcomes usually rank lower, but more important than how all these outcomes rank is that they always matter to employers, the report says.

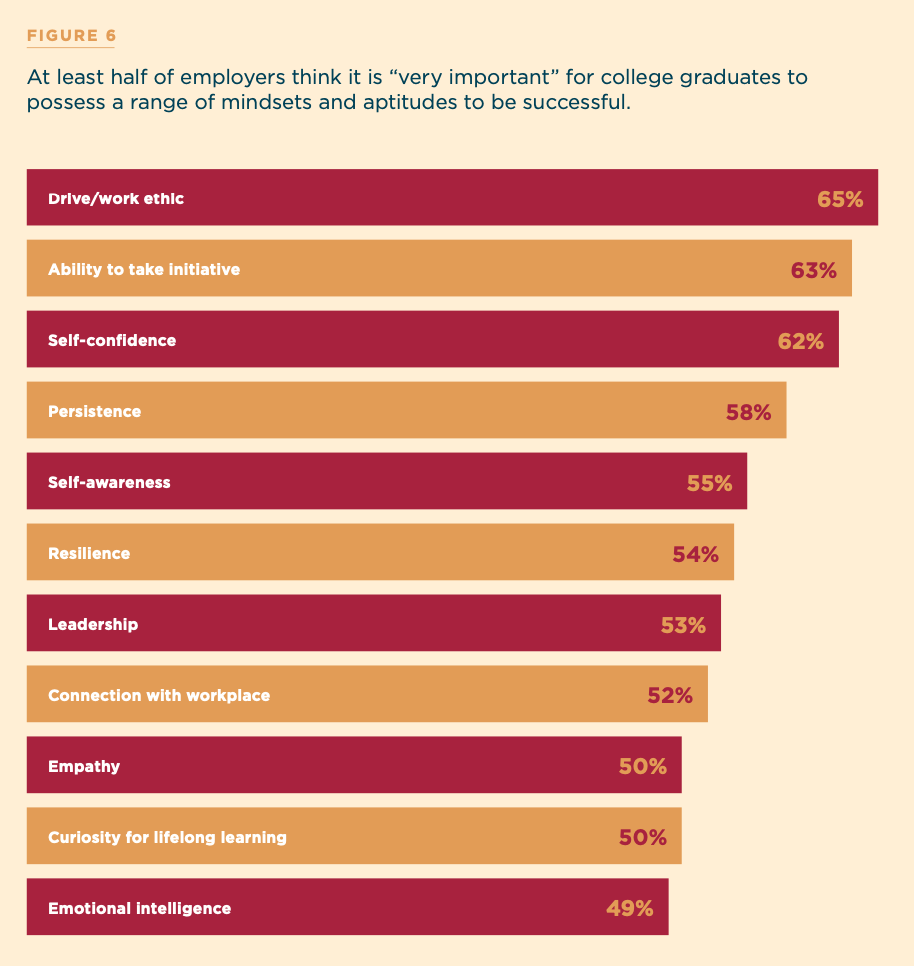

For this report, in addition to outcomes, the AAC&U asked employers about which and how mind-sets and aptitudes matter in hiring and the workplace.

Depth, Breadth and Mind-Sets

“We wanted to understand the degree to which employers value college graduates’ dispositions toward capacities such as expanding their learning, being self-motivated, engaging constructively with feedback, and persisting through failure,” the report says.

Results suggest that employers value these mind-sets and personal capacities like they value essential learning outcomes. At least half of employers view the skills of a liberal education as “very important” for college graduates. And at least half of employers think it is “very important” for college graduates to possess a range of mind-sets and aptitudes to be successful.

Results suggest that employers value these mind-sets and personal capacities like they value essential learning outcomes. At least half of employers view the skills of a liberal education as “very important” for college graduates. And at least half of employers think it is “very important” for college graduates to possess a range of mind-sets and aptitudes to be successful.

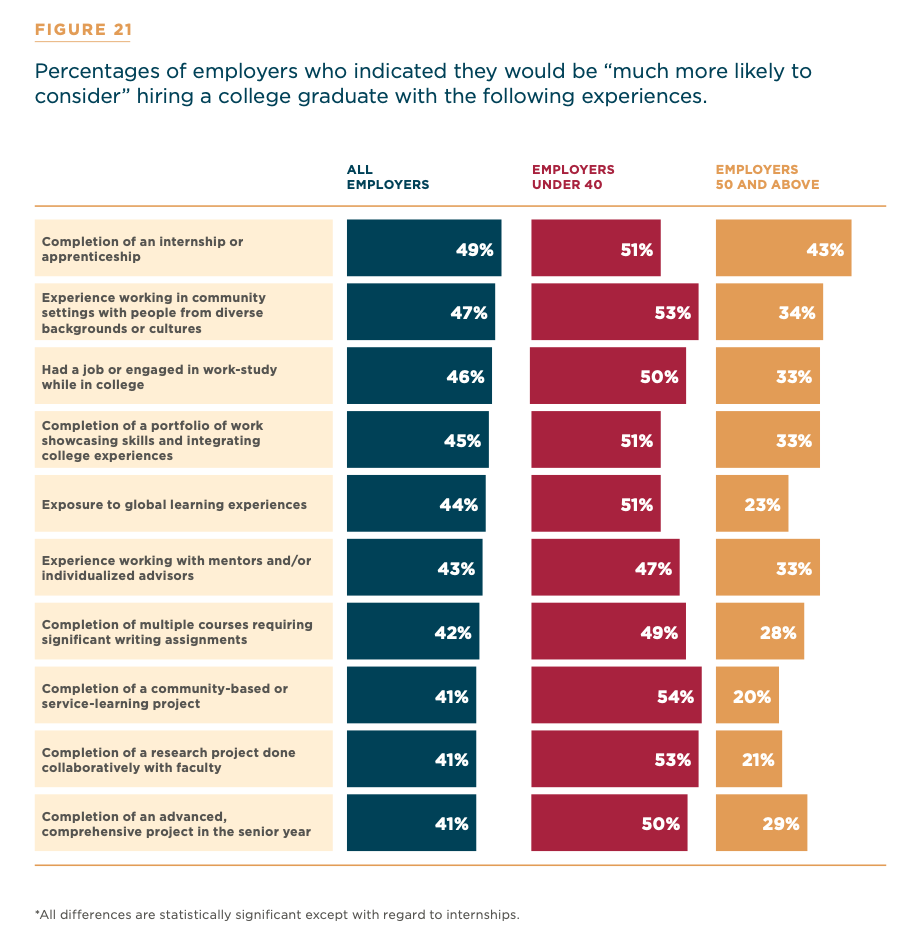

On high-impact practices, the AAC&U found that more than four in five employers would be either “somewhat more likely” or “much more likely” to consider hiring recent college graduates if they had completed an active or applied experience in college. Internships and apprenticeships top the experience list, followed by working in community settings with diverse community partners. Employers value work-study experiences and portfolios, along with global learning and mentored experiences. Comprehensive research and writing experiences stood out, too.

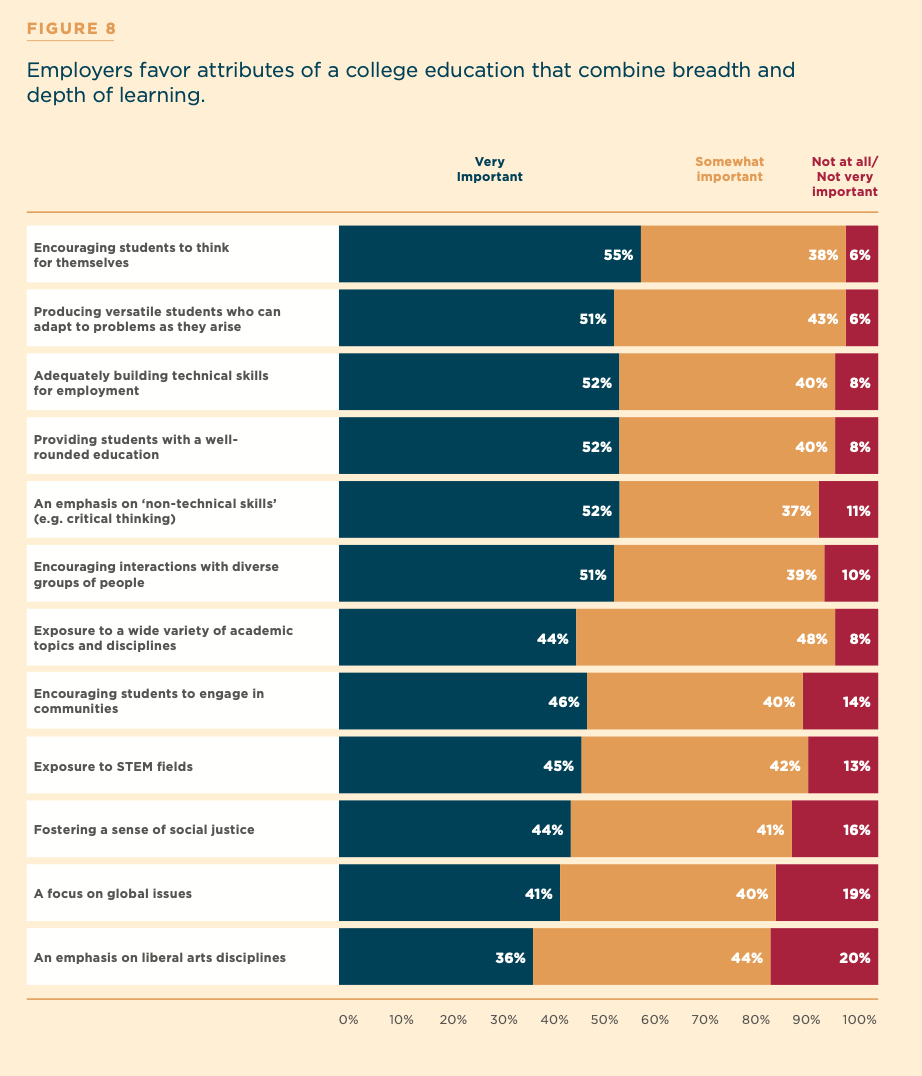

Employers said they appreciate breadth and depth of learning, too, as reflected in their desire that students learn to think for themselves, to be adaptable and versatile, to be technically capable and well-rounded. Ninety-two percent of employers said it’s very important or somewhat important that students have been exposed to a wide variety of academic topics and disciplines.

However prepared for work graduates may be, they need to communicate what they know to employers to get in an organization's door. Nearly nine in 10 employers said that recent college graduates are either “somewhat effective” or “very effective” in communicating what they learned in college. That’s a significant increase since 2018, when just 67 percent of employers said graduates were “at least fairly effective” at this.

While transcripts are still the primary written tool for communicating outcomes, the AAC&U has found again and again that employers do appreciate electronic portfolios in the hiring process. Nine in 10 employers said so in 2020, up from 2018. About half of employers would be “very likely” to click on an applicant’s portfolio if a link were provided.

“An ePortfolio is a personal website used to deepen student learning through reflection on, and curation of, work products produced across the college experience,” the report says. “These portfolios can be used by graduates to showcase and communicate their educational achievements.”

Room for Improvement

While nearly nine in ten employers (87 percent) said that they are at least “somewhat satisfied” with the ability of recent college graduates to apply the skills and knowledge learned in college to complex problems in the workplace, just 49 percent are “very satisfied.”

Six in 10 employers said that college graduates possess the knowledge and skills needed to succeed in entry-level positions, and 55 percent believe graduates have what it takes for advancement and promotion.

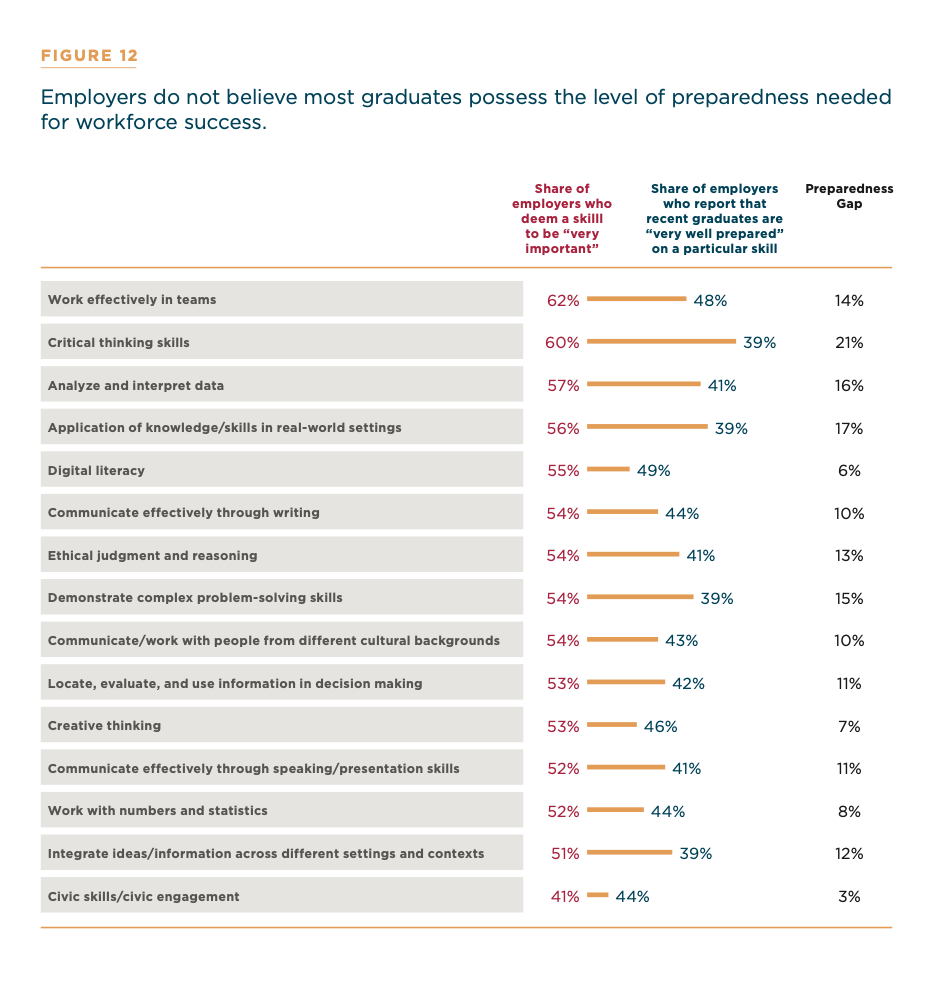

The AAC&U found both findings on perceptions of preparation striking. To better understand where employers were coming from, the association asked respondents to assess college graduates’ level of preparedness with regard to each of the learning outcomes deemed essential for success in the workplace. The difference between the two values is what the AAC&U considers to be the “preparedness gap.”

Whereas 62 percent of employers said working in teams is a very important skill, for instance, just 48 percent of employers said recent graduates were very well prepared to do it. The 14-percentage-point difference is the preparedness gap. The largest such gap was for critical thinking skills, at 21 percent. Analyzing and interpreting data was another big gap, as was applying knowledge and skills to real-world settings.

The report contains interesting findings about employers themselves. Employers under 40 are more racially and ethnically diverse than those over 50, and they are less likely to identify as white (69 percent versus 82 percent, respectively). Younger employers are also more likely to be women (41 percent versus 27 percent).

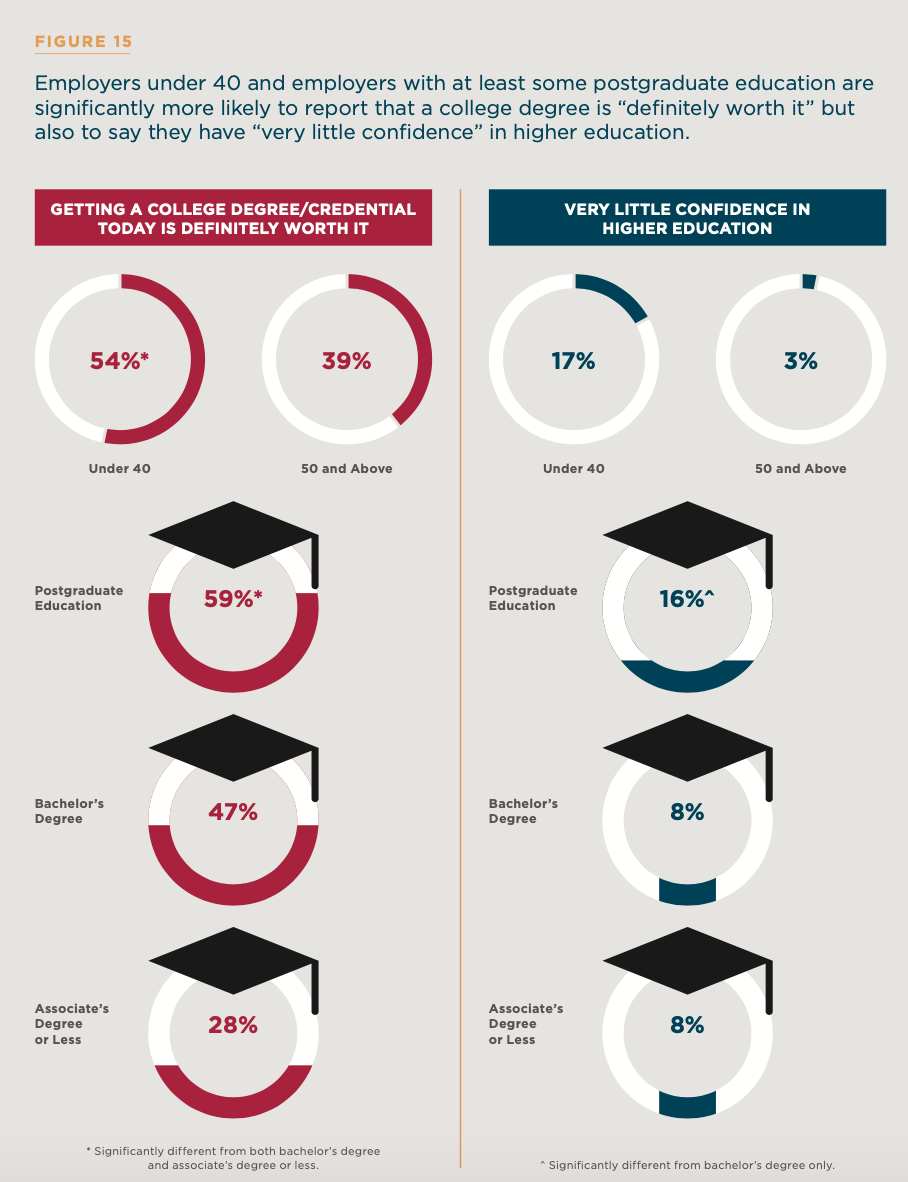

Beyond these demographics, younger employers and employers with higher levels of educational attainment have more favorable perceptions of both the value of the college degree and graduates’ preparedness for workforce success, according to the report. Interestingly, younger employers simultaneously have less confidence in higher education. Some 17 percent of those under 40 have “very little confidence,” compared to 3 percent of those over 50.

What employers value varies by age, as well. Drive and worth ethic matter more to older employers than younger ones. Younger employers value employees’ ability to work with numbers and data, their creative thinking, civic skills and engagement more. Leadership and empathy also matter more to younger employers than older ones.

Younger employers and employers with higher levels of educational attainment also see greater value in “civic skill-building, community-based and global experiences, and the civic and liberal arts emphases of a liberal education,” the AAC&U found. “With regard to the attributes or characteristics of a college education that most contribute to long-term career success, the largest differences between employers under 40 and those 50 and older were with regard to an ‘emphasis on global issues,’ ‘community engagement,’ fostering a sense of ‘social justice,’ and exposure to ‘liberal arts disciplines.’”

Younger employers and employers with higher levels of educational attainment also see greater value in “civic skill-building, community-based and global experiences, and the civic and liberal arts emphases of a liberal education,” the AAC&U found. “With regard to the attributes or characteristics of a college education that most contribute to long-term career success, the largest differences between employers under 40 and those 50 and older were with regard to an ‘emphasis on global issues,’ ‘community engagement,’ fostering a sense of ‘social justice,’ and exposure to ‘liberal arts disciplines.’”

The report ends with a series of recommendations for campuses. As employers widely endorse the skills developed via a liberal education, students must be equipped to “name and reflect” upon those skills -- particularly how they connect to workforce needs. Students must also be given a way to “tell employers their story,” according to the AAC&U. Transcripts are good here, “but ePortfolios are better.”

Educators must also make mind-sets and aptitudes an explicit part of learning, inside and outside the classroom. “Dispositions, ways of knowing and habits of mind are not solely innate traits,” the report says. “As with other skills and abilities, a college education cultivates these capacities through both curricular and cocurricular learning.”

Educators should assess students’ skills and mind-sets to ensure their preparation for not only securing a job but advancing once in that job, the paper says, noting the finding that employers doubt many students’ preparation for advancement. This is about outcomes and assessment, the AAC&U says: “The only way for campus leaders and educators to truly know if students are prepared to enter the workforce is to assess where students are on outcomes -- at the beginning, middle, and end of the college journey.”

Regarding equity, the report says that colleges and universities must make sure that high-impact learning experiences can be accessed by students from all backgrounds, and that all students are “supported to succeed” in these experiences.

“Job candidates with applied learning experiences have an edge in the hiring process,” AAC&U says. “It is not enough simply to make these learning experiences available on campus. Equity in access to, and success in, these experiences must be a priority for campuses that are committed to enabling students to flourish in college and in their careers.”

On general education, the report says it must reinforce breadth as well as depth of learning. “The skills that matter to employers are not developed within a single course or even within a single major,” the report says. “General education provides the entry point and foundational pathway for developing the skills, mindsets, and aptitudes that matter for workplace success. But that pathway must be aligned with majors to promote ongoing skill development, from cornerstone to capstone.”

The AAC&U has worked hard to end the perceived divide between what prepares someone for a well-paying job versus what prepares them for an enriching career. But job-ready rhetoric typically surges during economic downturns, like the one the global economy has experienced over the last year. Twenty-twenty was extraordinary in many ways, though, including that it delivered not only a recession but a racial reckoning, hard-to-swallow lessons about public health and health disparities, disinformation on overdrive, prolonged periods of isolation, and more.

Liberal Arts Skills Will Matter More Post-2020, Not Less

Asked about 2020 and hiring trends, Finley, at AAC&U, said the pandemic “has only increased the need for adaptability, problem solving, civic consciousness and perseverance. I suspect we will see much more of this in jobs, not less.”

Lynn Pasquerella, president of the AAC&U, said COVID-19 demonstrated “the ways in which the complex challenges we will be facing in the future, as individuals, as a nation and as members of a global community, will require the integration of skills and competencies across disciplines and the examination of issues from a diversity of perspectives.”

As just one example of these kinds of challenges, Pasquerella reflected on the “moral distress” experienced by doctors and other health-care providers over the last year: decisions about who gets a ventilator when those and other resources are scarce, how to treat patients without the proper personal protective equipment, and how to restore trust in the communities disproportionately affected by the virus.

“Their medical and technical training was insufficient when it came to grappling with the fundamental questions of human existence and how to meet their professional responsibilities in the context of pervasive issues of structural racism and classism,” Pasquerella said of these essential workers.

More generally, with 51 million Americans filing for unemployment within the first three months of the pandemic, Pasquerella said it’s “clear that students need the critical thinking, communication, creative and interpersonal skills that will enable them to become innovators in their own lives. A liberal education "fosters the adaptability and flexibility necessary to apply skills in a variety of contexts and respond to a rapidly changing world.”

Citing the Florida Legislature’s “troubling,” ongoing efforts to limit scholarship funding to majors that lead to "direct" employment, Pasquerella said one’s discipline “isn’t as important as the skills, outcomes and dispositions arising from integrative, applied learning -- which can be practiced in the context of the workforce.”

Things didn’t stop at 2020, either, Pasquerella continued. There are ongoing debates about when and how to reopen states, the January attack on the U.S. Capitol, and more. All have “raised a new sense of urgency around educating for democracy," for "preparing students for work, citizenship and life.”

Matt Sigelman, CEO of Burning Glass Technologies, a labor market and job skills analytics software firm that was not involved in the report, said his own data support much of those gathered by the AAC&U, especially in light of COVID-19.

"COVID has led to an increased demand for advanced skills generally," Sigelman said, adding that he's seen an increased employer emphasis on automation. The demand for advanced skills has also "stimulated demand for bedrock liberal arts skills."

Jobs that are the "most data-driven and technology-enabled actually request more liberal arts skills than the average job," he continued. These jobs are 50 percent more likely to require writing, 50 percent more likely to request research skills and 40 percent more likely to ask for problem solving, for instance, he said.

Liberal arts skills "are the ticket up, regardless of the profession," Sigelman said. "The further north in one’s career arc, the more valuable liberal arts skills, such as communication, prove to be."

Employers are also willing to pay a salary premium for liberals arts skills, he said. Engineering and information technology professionals can expect to make an additional $14,000 annually for leadership skills, $12,000 for presentation skills and $2,000 for writing skills, based on a median salary of $81,000, according to information from Burning Glass.