You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

COVID-19 has widened the prosperity divide among Australian universities, leaving richer institutions with the means to keep expanding while their poorer cousins are downsizing—perhaps permanently.

A Times Higher Education analysis of Australian universities’ financial accounts suggests that the pandemic and other global disruptions may have reset the higher education power balance even more in larger institutions’ favor.

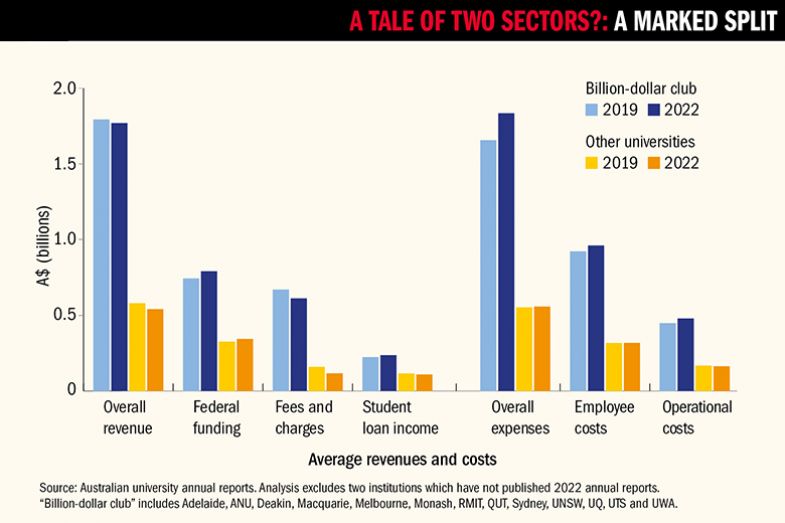

While the 13 wealthier universities—those with total revenues exceeding one billion Australian dollars ($650 million USD) in 2022—have been unsettled by the upheavals of the past few years, the financial impacts have been far from catastrophic. On average, they attracted just 1 percent less funding in 2022 than they had in 2019. Increased income from federal government grants and the Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) more than compensated for the deterioration in earnings from tuition fees and other charges.

It has been a different story for around two dozen sub-billion-dollar universities, whose average revenue declined by 7 percent between 2019 and 2022. The increase in direct federal funding over that period amounted to slightly over one-third of the income they lost through reduced fees, charges and HELP receipts.

The richer institutions found the wherewithal to spend 11 percent more in 2022 than in 2019, with their outlays rising by an average of 4 percent on personnel and around 7 percent on operational expenses such as travel, consumables, professional services, information technology and student scholarships. The poorer universities’ average spending on operating expenses was 3 percent lower in 2022 than in 2019, while their employee-related expenditures grew by just 0.06 percent—suggesting that their human resources have almost certainly shrunk, given the recent inflationary pressures on salaries.

The analysis is based on data from the annual reports of all Australian universities that had published detailed 2022 financial accounts at the time of writing, including every public institution apart from Flinders University and the University of Canberra. THE chose 2022 as the post-COVID reference year to avoid confounding factors such as the 2021 injection of an extra A$1 billion of research funding, which mostly went to richer institutions, and wild fluctuations in the investment markets in 2021 and 2022.

Among the 36 universities included in this analysis, the poorer institutions educate 71 percent of domestic students from low-socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds, according to the latest available Education Department data. In other words, the segment of the sector that caters to the bulk of equity students—the Labor government’s policy priority—may have had its capacity severely weakened by recent global disruptions, unlike the segment that caters predominantly to students from well-heeled backgrounds.

Ant Bagshaw, a senior adviser with LEK Consulting, said institutional financial accounts did not reveal how much some universities may have delayed or shelved efforts to maintain and renew their facilities.

“The headline figures of revenue and expenditure can often mask delayed maintenance activities or missed opportunities for investment, as institutions come under more financial stress,” Bagshaw said. “We need to be cognizant that the situation might be worse than what is revealed in the immediate financials.”

The Universities Accord panel’s interim report notes that some Australian universities have substantial endowments and “valuable property holdings,” while their lofty international rankings help attract overseas students in large numbers. Other institutions “do not have access to these benefits and face challenges to their financial stability,” the report observes. “As a result, many universities are in a precarious financial position.”

While the accord panel has yet to produce its substantive recommendations, ideas floated in the interim report suggest a move away from market-based policies toward mechanisms that could benefit smaller suburban and regional universities. One proposal under consideration is a “needs-based” funding model that recognizes the additional costs involved in teaching equity students.

“The implication of the interim report is that the government has recognized that it is much harder going for a whole swath of our universities, and that some corrective action is therefore needed to support those institutions that are doing the most to support students from diverse backgrounds,” Bagshaw said.

Tertiary education consultant Claire Field said there was evidence that the pandemic had disproportionately harmed low-SES communities, eroding parents’ capacity to support their offspring at university, and increasing pressure on school leavers to immediately start earning. COVID also disproportionately affected the school experience of people in disadvantaged areas, leaving them less academically prepared for higher education.

“In another year or two, when we look at schooling data, I suspect we’re going to see more students from low-SES backgrounds going straight into work,” Field said.

She said the less resource-rich universities’ stagnant salary spending could reflect an overall reduction in staff numbers or a shift to cheaper casual staff. Alternatively, these institutions may have cut back on key revenue-generating employees such as the people who recruit and support international students.

She said Chinese students, who gravitated to wealthier Australian universities with globally recognized brands, had Beijing’s approval to study online during the pandemic. The government in India, the primary market for more modest Australian institutions, did not recognize the validity of qualifications obtained remotely from abroad. While more data would be needed to build a clear picture of staffing patterns, the indications were that changes during the pandemic—including the extra research funding, now expired—enabled the richer institutions to make choices unavailable to the others.

“No one had a fantastic pandemic, [but] all the factors that make the research-intensive universities financially stronger played into their favor. [They] receive more research funding [and] attract a different type of international student, who is wealthier. They didn’t have to restart their international education in quite the same way as poorer universities, and they attract different domestic students,” Field said.

“The non-research-intensive universities got less research income. [They] attract more low-SES students and poorer international students, so they need more of them to generate the same levels of revenue. Those students were less likely to be studying online during the pandemic. All of those factors may have made the pandemic a much harder experience.”

Australian National University policy analyst Andrew Norton said it was “too early to tell” whether COVID had changed the institutional balance in a lasting way. He said the past three years were also tough for the richer institutions, with earnings falling at all but three and spending rising at all but two. “Lower revenue and higher expenses is a bad match,” he observed.

Norton noted that some “high-prestige-brand” institutions attracted lower amounts from student loans, notwithstanding overall fee increases that should have increased their HELP receipts. He said that while there was “striking” variation in institutional earnings from the different income streams, it was difficult to tease the pandemic’s impacts apart from the “normal cyclical effects” of the economy, as strong job opportunities lured people away from study.

Paul Harris, executive director of Innovative Universities Australia, agreed that more data were needed to unpack COVID’s impacts on the sector. “There are all sorts of other things going on under the surface that these numbers don’t help us get at,” he said.

Nevertheless, examining pre- and post-pandemic institutional finances was a “useful exercise,” particularly as a major higher education review tackles questions about how the government should apportion public funding to universities.

“How do you best allocate your public dollars to maximize the return on investment for the public good? I think you need to take into consideration other sources of revenue. Should [government] be giving less public money to institutions that [have] lots of other sources of revenue? That’s a key part of the accord discussion that we’re going to have to come to grips with.”