You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

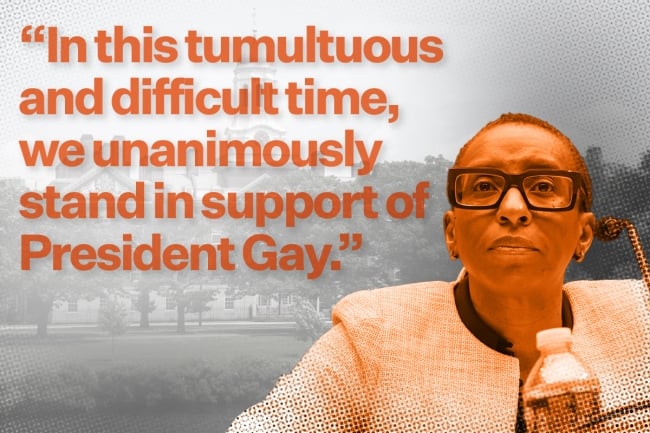

The Harvard Corporation issued a statement of support for President Claudine Gay on Tuesday.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Getty Images

Harvard University president Claudine Gay will keep her job following a firestorm of controversy related to admitted missteps at a congressional hearing and sudden accusations of plagiarism.

The Harvard Corporation, one of the university’s two governing boards, released a statement of support Monday, breaking its silence in the face of critics who have called for Gay’s ouster following her equivocating responses during last week’s House hearing on antisemitism in higher education. The board made clear Monday that it stands behind Gay.

“As members of the Harvard Corporation, we today reaffirm our support for President Gay’s continued leadership of Harvard University. Our extensive deliberations affirm our confidence that President Gay is the right leader to help our community heal and to address the very serious societal issues we are facing,” board members said in a statement Tuesday morning.

The board, which met Sunday and Monday, also addressed Gay’s controversial remarks from the Dec. 5 congressional hearing. Gay—who was questioned alongside fellow presidents Sally Kornbluth of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Elizabeth Magill of the University of Pennsylvania—has been criticized for failing to state directly that calls for the genocide of Jewish people would violate Harvard’s policies. Kornbluth and Magill were blasted for giving similarly evasive answers, prompting the Penn president to resign last week following months of campus tensions.

The Harvard Corporation noted in its statement that Gay has apologized for her responses.

“So many people have suffered tremendous damage and pain because of Hamas’s brutal terrorist attack, and the University’s initial statement should have been an immediate, direct, and unequivocal condemnation,” the statement read. “Calls for genocide are despicable and contrary to fundamental human values. President Gay has apologized for how she handled her congressional testimony and has committed to redoubling the University’s fight against antisemitism.”

Months of Tensions

The congressional hearing generated national headlines, but Gay was already facing criticism for Harvard’s response to a letter signed by more than 30 student organizations that declared solidarity with Palestinians following deadly attacks by Hamas on Israeli civilians on Oct. 7. The letter declared that the “Israeli regime” was “entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.”

Backlash quickly erupted. Employers threatened a boycott on hiring students who supported the Palestinian cause. A doxing truck, sponsored by the conservative organization Accuracy in Media, drove around campus calling students who had purportedly signed the anti-Israel statement “Harvard’s Leading Antisemites.”

As outrage grew, Gay issued a statement in which she condemned “the terrorist atrocities perpetrated by Hamas” but did not criticize student leaders for their rhetoric. She did, however, emphasize that student opinions were not reflective of institutional stances.

“Let me also state, on this matter as on others, that while our students have the right to speak for themselves, no student group—not even 30 student groups—speaks for Harvard University or its leadership,” Gay wrote in a presidential statement issued on Oct. 12.

By the time Gay arrived on Capitol Hill for the House hearing, tensions were high.

Uniform missteps by the presidents—none of whom had been in the job for more than two years—drew immediate ire. Politicians, donors and other critics expressed outrage at the legalistic answers the campus leaders provided. In the aftermath, 74 members of Congress wrote to Harvard, Penn and MIT calling on them to fire their presidents.

Magill, who also faced criticism from Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor over her responses at the hearing, resigned under pressure over the weekend. Critics rejoiced; Republican representative Elise Stefanik, who grilled the three top executives at the hearing, declared on X, “One down. Two to go”—a sentiment former president Donald Trump later echoed.

While MIT’s Board of Trustees was quick to express its full support of Kornbluth, Gay did not receive the same backing right away.

And before the Harvard Corporation issued its statement, a new controversy emerged when conservative activist Chris Rufo accused Gay of plagiarizing her Ph.D. thesis while a graduate student at Harvard. In a series of posts on X, Rufo declared that Gay had lifted passages from other authors “nearly verbatim” when writing her award-winning dissertation in the late 1990s.

Gay batted away the accusations in a statement Monday.

“I stand by the integrity of my scholarship. Throughout my career, I have worked to ensure my scholarship adheres to the highest academic standards,” she said.

Rufo—a trustee at New College of Florida and a well-known critic of diversity, equity and inclusion practices—issued a call for Gay’s firing as he touted the plagiarism allegations. He acknowledged he made the claims the same week as Harvard’s board meeting for “maximum impact.”

Plagiarism Accusations

On social media, academics have largely brushed off the plagiarism claims. Many suggested that the charges were overblown and that Rufo didn’t understand research citation standards.

Two of the authors that Rufo claimed Gay plagiarized weighed in; one, Gary King—a Harvard professor who was Gay’s thesis adviser—dismissed the allegations, telling The Daily Beast that her dissertation “met the highest academic standards.” King added that Rufo’s claims were “ridiculous” and “absurd.”

Carol Swain, another author, argued that the Harvard president had been “sloppy” and that Gay’s body of work drew heavily from her own. Swain, a retired academic who writes about the intersection of race and politics, suggested that Gay had largely copied her research agenda. But in an interview with Rufo, she stopped short of directly accusing Gay of plagiarism.

The Harvard Corporation—which has the power to hire and fire presidents—addressed the plagiarism claims in its statement of support Tuesday.

“With regard to President Gay’s academic writings, the University became aware in late October of allegations regarding three articles. At President Gay’s request, [board members] promptly initiated an independent review by distinguished political scientists and conducted a review of her published work. On December 9, [board members] reviewed the results, which revealed a few instances of inadequate citation,” the Harvard Corporation said in its Tuesday statement.

Ultimately, “the analysis found no violation of Harvard’s standards for research misconduct,” board members wrote, noting that the president is “proactively requesting four corrections in two articles to insert citations and quotation marks that were omitted from the original publications.”

In response, Rufo accused Harvard of academic double standards in a post on X: “During her tenure as dean, Claudine Gay required dozens of students to withdraw from the university for violating academic integrity standards, especially on plagiarism. Now, as president, the board has allowed her to flout those same rules. It’s pure hypocrisy, justified by DEI.”

Swain, who is Black and a conservative, wrote on X that she was “angry” and accused Harvard of “racial double standards,” with white progressives protecting Gay, apparently for ideological reasons.

Supporters of Gay, including Morehouse College president David Thomas, by contrast, have suggested the inverse—that criticism regarding her scholarship lacks legitimacy and derives from discomfort about diverse leadership at acclaimed American institutions like Harvard.

Similar Situations, Different Outcomes

While the Magill and Gay controversies started out similarly, the outcomes were sharply different.

Harvard’s board members stood by Gay, while Penn’s did not have Magill’s back. Immediately after Magill resigned, board chair Scott Bok announced he was also stepping down.

One clear distinction between the cases: the Penn administration allowed a Palestinian literary festival to proceed in September, despite calls from donors and powerful Jewish organizations to cancel the event, which featured several controversial speakers. So tensions over Israeli-Palestinian relations were already flaring on the Penn campus before the deadly attacks by Hamas triggered a war with Israel.

Another difference between Magill and Gay is their ties to their universities. Magill, who became president in 2022, had no prior connection with Penn. By contrast, Gay earned her Ph.D. at Harvard in 1998, joined the faculty in 2008 and rose through the ranks, serving as dean of Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences beginning in 2018 before she was named president last year. Gay officially stepped into the role this summer, becoming the first Black person to hold the job.

While Magill has not publicly addressed her resignation beyond a brief statement, Bok wrote a recent opinion piece in The Philadelphia Inquirer that offers some insights into donor pressures at Penn, with the ex–board chair cautioning universities “to be very careful of the influence of money.”

Bok emphasized that donors shouldn’t determine campus policies or curricula—despite the fact that philanthropists and foundations have threatened for months to close their checkbooks unless Magill resigned or was fired by the board.

Bok noted that for the 19 years he served on Penn’s board, there was “a very broad, largely unspoken consensus on the roles of the various university constituencies: the board, donors, alumni, faculty, and administration,” suggesting that in recent years, donors had come to expect more input into the operations of the university.

“Once I concluded that this longtime consensus had evaporated, I determined that I should step off the board and leave it to others to find a new path forward.”

His column included a sentence that can be interpreted as either a reflection or a warning.

“The culture wars can be brutal,” Bok wrote.