You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

University of Idaho president Scott Green shares his insights on handling campus crises.

University of Idaho

Since decamping from the corporate world and taking the helm of the University of Idaho in 2019, President Scott Green has led his alma mater through a series of crises. First came financial issues, followed by the coronavirus pandemic. Then the mysterious murders of four students in fall 2022 captured headlines and left the campus and small community of Moscow, Idaho, on edge for months until the alleged killer was apprehended.

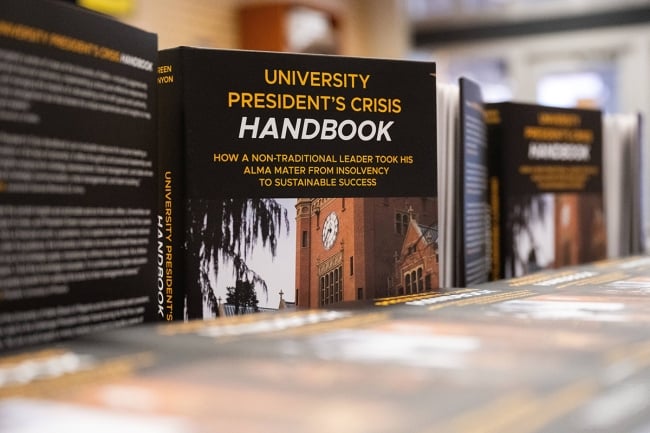

Green has distilled lessons learned from those crises into a new book, co-authored with writer Temple Kinyon: University President’s Crisis Handbook: How a Non-Traditional Leader Took His Alma Mater From Insolvency to Sustainable Success (Wiley).

He recently spoke with Inside Higher Ed via Zoom about the book and the events that inspired it. Excerpts of the conversation follow, edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your presidency started with a financial crisis, and the university had to make some hard decisions. Looking across the higher ed landscape, it’s clear that many institutions are struggling. How should leaders communicate when hard choices lie ahead?

A: Really, I was hired because we were already having financial issues. But the community didn’t know about all those issues, so we did have to get out in front of it. Before I even started, I asked the former president and chief financial officer to make sure that the community was aware of where exactly they were [financially], because I was reviewing the information and if I could figure it out, being a new person, they should be able to communicate to their community—which they did, and they did a great job. By the time I arrived, people recognized that we were in a financial crisis. There was a sense of urgency, which we needed.

As a first step, I asked the deans to go back and cut, and we set targets for that. While there was pushback from some faculty and staff, I think largely that everybody got it, and we held town halls, we had discussions about it. I stayed in those town halls until every question was answered. We wanted people to know that we heard their concerns and we were going to do our best to address our financial issues, but do so in as empathetic a way as possible. A lot of presidents are dealing with this now, and it’s going to get worse with the enrollment cliff coming. I think a lot of institutions are not prepared for that and they’re going to face it shortly. That’s one of the reasons why I decided to write this book and spend so much time on the financial crisis.

Q: The decision to have in-person classes in fall 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic upset a lot of people. As you note in the book, some faculty suggested the decision was unethical and would lead to numerous deaths—even though the university’s own assessment said otherwise. How do you cut through the noise of competing claims on charged topics?

A: We made the decision early on to rely on subject matter experts and people that we could trust to give us informed facts rather than emotional responses. We had a small number of faculty who decided they were experts and they knew better than our subject matter experts. But many of them were not trained in these fields, so we relied on experts at Gritman hospital, Idaho Department of Public Health and our own medical faculty and data scientists. Long before others came out with claims or other data, we already had the models, the information coming in, the opinions of medical experts.

And we did close early in the pandemic, but we had all summer to prepare, and by the fall we had our own lab set up and running so we could test students as they came in. We had our own infirmary to care for our students and to take pressure off our local hospital, which never did enter a crisis standard of care like most across the country. We had hand sanitizer in every building that we made ourselves, we had social distancing and technology set up in every classroom so we could deliver classes safely, and not a single case of the virus was ever contact-traced back to one of our classes, or to one of our labs, by public health. Yes, we had outbreaks on campus, but we think we did a very good job of identifying it early through testing, through wastewater testing and tamping those hot spots down.

Q: You mention a number of higher education third-rail subjects in the book—lawsuits, athletics, accreditation, politics. Are there other third-rail topics you would add, and how should presidents approach them?

A: I may discover more third rails, and I’m sure other presidents would identify others that are specific to their institution or the culture of their community or the state of doing business.

My advice is to get a lot of input from subject matter experts. And if you can rely on outside experts that you can point to, that takes a lot of pressure off of your administration. And react with empathy in all cases, show that you care and that you understand that this has an impact on your employees and your students. My advice is to move carefully and lead in an empathetic way. What I found is that if you can explain why you’re doing things, and people understand that you care about them, they will follow you, and they will give you a chance to prove yourself. That was the case with the pandemic and certainly most of the crises we’ve had here on campus.

Scott Green (left) and Temple Kinyon (right) at a book event.

University of Idaho

Q: The book discusses how the conservative political group Idaho Freedom Foundation cast the university as indoctrinating students [into left-wing concepts such as critical race theory] and how you pushed back strongly on those claims. Similar things are happening across the U.S., including in Florida and Texas. How should presidents address those claims? And what are the inherent risks in doing so?

A: First of all, we were very careful not to criticize the Legislature or legislators who were being fed information by the Idaho Freedom Foundation. It seems to me when we responded, they were often surprised by the response and that maybe they didn’t have good information.

I was always, always very careful to try to not judge [legislators] for having asked the [indoctrination] question in the way that they did. A lot of times it doesn’t pay—particularly if you find yourself at odds with the Legislature—to take it on. And I’m not encouraging anybody to do that. But those people who are feeding the Legislature—the conflict entrepreneurs, the ones who make their money off of creating conflict and creating discontent—are fair game. We hired an outside law firm and subject matter experts to come in and evaluate the claims that they were making, and they were making them in the guise of research reports.

Well, there was no analysis or academic rigor to any of those reports. They were political puffery, to advance a political agenda. What [the independent] reports found was that the IFF claims could not be substantiated because it was a political position to create conflict to get people scared and to raise money.

Q: Something I’ve written about recently is how difficult it can be for presidents to discuss political issues and whether it even makes sense to do so. What issues should presidents engage on? And what kind of cost-benefit analysis should they do when considering whether to speak up?

A: We actually have a policy on this: we only comment when it has a direct impact on our community. There are people who want us to comment on every tragedy that happens around the globe, and we just don’t have time to do that. It has to be really relevant to our community, of great interest to the majority and in the interest of the university to respond. We do respond from time to time, but by and large, we try not to, because it’s not the position of the university that we should be weighing in on decisions that have very little to do with our community.

Q: You dealt with a horrific crisis when four students were murdered in 2022. What was your initial reaction to the news? How does a president even begin to address such a shocking tragedy?

A: It’s something I still have trouble talking about, if I’m being completely honest. My initial reaction was the same one I have now: profound sadness for those students and those families. Because of that, I don’t like to talk about it much. But we did have to respond, and I had a great team. We had a crisis management team before this ever came up, but you can’t ever prepare for something like this. We got the team assembled early; we worked through the night figuring out next steps and how we could help police identify the students. I wouldn’t be completely honest if I didn’t say that there was a lot of emotion in the room, which ranged from sadness to anger because of what had happened.

Q: The brutal nature of the murders prompted a lot of sensationalist coverage and online conspiracy mongering. How did you keep the story straight when information on the case moved at a much slower pace than the speculation? And how did you communicate such horrific news to the campus, especially when students were afraid and the killer was still at large?

A: Our strategy was to focus on our employees, our students and their safety, and remind people that law enforcement had a job to do and that it would be wrong for any of us to speculate about who the murderer was, and to accuse potentially innocent people. The students, in particular, got it, because they’re probably more savvy about social media than any of us. It was the employees and some of us who are of a different generation that really struggled with this, but we got the message out that the police will do their job, and we have every confidence in them that they will identify who this is. It was painful, but we just had to continue to communicate to our students about what we were doing to keep them safe. Because that is what everybody was focused on. A large part of our community was very afraid, and parents were concerned about sending their students back to campus if the person had not been apprehended.

We substantially increased the security on campus. We had the Idaho State Police everywhere. We also provided an online option to parents who were uncomfortable sending their kids back to campus, back to the city of Moscow. We were working on all of that when they apprehended the accused. And then of course that changed everything and everyone felt much better.

Q: The book briefly mentions the importance of taking care of yourself in highly emotional situations. How did you do that, and how important is self-care for presidents when dealing with tragic situations?

A: It may be different for every president, but I learned a lot during the pandemic. There was a point early on in the pandemic where, at the end of the week, I was so exhausted I couldn’t respond to anyone anymore. I literally had to go to bed early, and there were important things to do but I couldn’t physically do it anymore. I never forgot that, because I felt like I wasn’t doing my job at that point in a very competent manner. I was getting very little sleep; we were responding, we were planning, doing all these things to respond to the virus and to close down the university in a safe manner at that time. When the capital crimes occurred, all that was not lost on me.

We did a great job, I think, at the university, but I did a very poor job of managing myself. So during the capital crimes I was very cognizant and thoughtful about getting to bed early, getting up early and working out—I wasn’t going to miss my workouts. And making sure that I had blocks on my calendar, time to actually think through things and call people for advice rather than just reacting, just so that I could make better decisions, because the university deserved that. Our community deserved that. I would just encourage any president to make sure to make time for themselves not only for self-care physically, but mentally. Find blocks of time where you can really just sit back and think about what you need to do, who you need to call, what kind of advice you need, so that you can make the best decisions for your institution.

Q: You share a number of management insights throughout the book. Are there any in particular you would like to highlight? Any big takeaway that you hope to leave readers with?

A: It’s really important that you surround yourself with subject matter experts and rely on people who are calm, collected and informed—not emotional and scared. Also, lead with empathy. People need to understand that you care about them, you’re making decisions—not just for the institution but for them, because they are part of that institution, part of our family. I think often that’s lost; people like to think of themselves as decision-makers and very analytical. Now that’s really important, but there has to be room in the discussion for empathy. If not, you’re not going to be able to communicate appropriately to all stakeholders. They need to know you get it.