You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

As AI-driven fakery spreads—from election-related robocalls and celebrity deepfake videos to doctored images and students abusing the powers of ChatGPT—a tech arms race is ramping up to detect these falsehoods.

But in higher ed, many are choosing to stand back and wait, worried that new tools for detecting AI-generated plagiarism may do more harm than good.

“Twenty-five years ago, you were grabbing at your student’s text saying, ‘I know this isn’t theirs,’” said Emily Isaacs, director of Montclair State University’s Office for Faculty Excellence. “You couldn’t find it [online], but you knew in your heart it wasn’t theirs.”

Montclair announced in November—a year after the launch of ChatGPT—that academics should not use the AI-detector feature in a tool from Turnitin. That followed similar moves from institutions including Vanderbilt University, the University of Texas at Austin and Northwestern University.

A big question driving these decisions is: Do AI-detection tools even work?

“It’s really an issue of, we don’t want to say you cheated when you didn’t cheat,” Isaacs said. Instead, she said, “Our emphasis has been raising awareness, mitigation strategies.”

Awareness of AI-driven falsehoods and the perils of plagiarism has skyrocketed. This week, Meta—parent company of Facebook and Instagram—announced it would label AI-generated images. That followed an uproar caused by fake, AI-generated pornographic images of singer Taylor Swift circulating online and AI-powered robocalls impersonating President Joe Biden that sought to suppress votes in the New Hampshire primary. The Federal Communications Commission outlawed such AI robocalls on Thursday.

Meanwhile, discussions of plagiarism and its detection have surged since Harvard’s now former president Claudine Gay was accused of plagiarizing portions of two previously published articles. Gay resigned in the wake of that and after a congressional hearing on antisemitism in higher education.

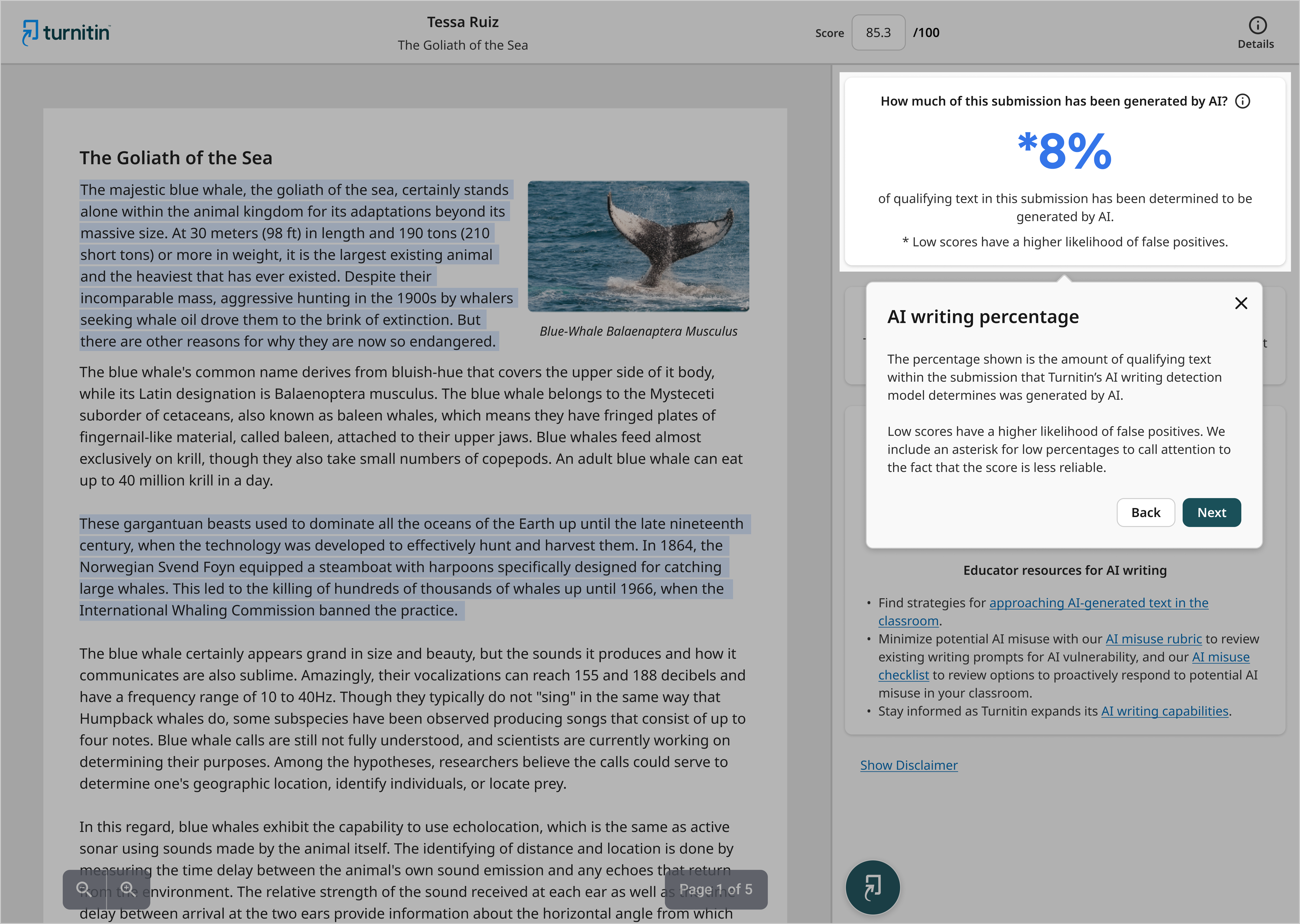

With faculty spending more than a year fretting about the potential abuse of AI tools like ChatGPT, technology companies such as Turnitin have touted the benefits of AI detectors. The tools, typically integrated into other grammar and writing software, scan text like a spell-checker or antiplagiarism program.

Turnitin says its AI-detection tool, in an attempt to avoid false positives, can miss roughly 15 percent of AI-generated text in a document.

“We’re comfortable with that since we do not want to highlight human-written text as AI text,” the company’s website says, pointing toward its 1 percent false-positive rate.

The detection tools have raised their own questions, and for many institutions there are no clear-cut answers.

“The idea of being all for it or entirely against it, I don’t know if it breaks down like that,” said Holly Hassel, director of the composition program at Michigan Technological University. “You imagine it as a tool that could be beneficial while recognizing it’s flawed and may penalize some students.”

The Effectiveness of AI Detectors

In June last year, an international team of academics found a dozen AI-detection tools were “neither accurate nor reliable.”

That same month, a team of University of Maryland students found the tools would flag work not produced by AI or could be entirely circumvented by paraphrasing AI-generated text. Their research found “these detectors are not reliable in practical scenarios.”

“There are a lot of companies raising a lot of funding and claiming they have detectors to be reliably used, but the issue is none of them explain what the evaluation is and how it’s done—it’s just snapshots,” said Soheil Feizi, the director of the university’s Reliable AI Lab who oversaw the Maryland team.

In November, two professors from Australia’s University of Adelaide conducted AI-detection experiments for Times Higher Education (Inside Higher Ed’s parent company).

Some tools, including Copyleaks, fared better than others, but the professors summed up their findings with a singular warning: “The real takeaway is that we should assume students will be able to break any AI-detection tools, regardless of their sophistication.”

The investigations themselves raised concerns about feeding students’ work to the generative AI tools, where it’s “not clear what’s done with it,” Isaacs said.

Isaacs and Feizi noted other problems, including that there is no evidence trail when the tools flag suspected AI writing.

“With the AI detection, it’s just a score and there’s nothing to click,” Isaacs said. “You can’t replicate or analyze the methodology the detection system used, so it’s a black box.”

Turnitin's AI detector

Turnitin

Annie Chechitelli, chief product officer at Turnitin, emphasized the importance of teacher-student relationships, rather than relying solely on technology tools.

“Detection is only one small piece of the puzzle in how educators can address with AI writing in the classroom,” Chechitelli said in a statement to Inside Higher Ed. “The largest piece of that puzzle is the student-to-teacher relationship. Our guidance is, and has always been, that there is no substitute for knowing a student, knowing their writing style and background.”

Despite their skepticism of the detection tools, Feizi and other researchers support the use of AI technology over all.

“A more comprehensive solution is to embrace the AI models in education,” Feizi said. “It’s a little bit of a hard job, but it’s the right way to think of it. The wrong way is to police it and, worse than that, is to rely on unreliable detectors in order to enforce that.”

Beginnings of an Approach on AI Detection

The Modern Language Association and the Conference on College Composition and Communication have been careful in giving guidance about AI detectors. The two groups formed a joint task force on writing and AI in November 2022, publishing their first working paper in July.

“We don’t take a formal stance, but we have a principle that tools for accountability should be used with caution and discernment or not at all,” said Hassel, co-chair of the task force and professor at Michigan Technological University. She added that among the task force members, there’s a range of approaches to the tools, with some banning them entirely.

The group’s second working paper, delving further into AI detection and the usage of tools, is slated for completion this spring.

Elizabeth Steere, a lecturer in English at the University of North Georgia, has written about the efficacy of AI detectors. She and other UNG faculty members use the AI detector iThenticate from Turnitin. Students’ work is automatically checked when they turn in assignments to their Dropbox.

Several journals also use the iThenticate tool, although the value of the costly software has been debated. Turnitin, the company behind iThenticate, offers customized pricing based on organizations’ size and needs. Otherwise, it’s generally $100 for each manuscript of fewer than 25,000 words.

Steere said the AI detector is just one tool in preventing plagiarism.

“It is a fraught issue, and each institution really does need to weigh the pros and cons and come to their own decisions, because it’s complex—it’s thorny,” she said.

The issue is further complicated by the inclusion of AI in common writing tools, like Grammarly, Google Docs and various spell-checkers.

“A lot of times it was [students saying], ‘No, I didn’t use AI,’ then it comes out they were using an overall rephrasing tool, not thinking it’s an AI tool,” Steere said. “The boundaries are much blurrier now; I really feel for the students, because we didn’t have that when we were in school.”

Steere uses those instances as teachable moments to explain the various degrees of plagiarism.

“If every student said, ‘I didn’t use AI,’ and I say, ‘Yes, you did,’ it’s not helping anyone,” she said. “But you can speak with them directly and figure out their writing process—have they used tools or augmenting, and do they consider that to be AI?”