You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Social media and the blogosphere have been awash for weeks with outrage that university chancellors and presidents are urging their faculty and students to conduct campus debates in a civil manner. The debates in question are mostly about the Arab/Israeli conflict, debates that have intensified since this summer’s war in Gaza. Those who relish their free speech right to denounce one another are taking umbrage at any suggestion that reasoned discussion might benefit from reluctance to indulge in mutual hatred.

Printed posters carried aloft in a September demonstration at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign read “Civility = Silence. Silence = Death.” In a particularly hyperbolic move, Henry Reichman, chair of the American Association of University Professor’s Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure, claimed that charges of incivility are being used to silence faculty members in the same way that accusations of communist sympathies were used to silence them during the McCarthy period of the 1950s. Historical comparisons should be carefully justified. This equation is at best frivolous; at worst it risks fomenting unwarranted feelings of victimhood.

Faculty members and students share with all Americans the right to indulge in uninformed and intemperate speech. Social media provide them with effective means for doing so. But does unrestrained antagonism make for the best learning environment? Does it advance knowledge in the way higher education is pledged to do? Does it train students to evaluate evidence dispassionately? Does it prepare students to participate productively in public life? Does it help students learn that it is possible, indeed preferable, to be zealous in advocating a point of view without vilifying or trying to silence those who differ?

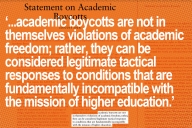

These effects include long-term consequences. The immediate effects of uncontrolled campus hostility can be more dramatic. We have already seen intemperate campus speech escalate toward violence. That happens most often with debates over Israel. Indeed verbal excess, aggression, and ad hominem attacks are part of the standard repertoire of the Boycott, Sanctions, and Divestment movement. That typically stimulates raised tempers and sometimes similar behavior on the pro-Israeli side. Nothing good comes of these confrontations.

We have recently seen campus passions cross the line into a moment of physical violence at Temple University. We saw extreme speech and symbolic action degenerate into threats, accusations, and even arrests at Ohio University. If we add to the list instances when campus groups sought to undermine academic freedom by denying invited speakers the right to speak the list of examples would grow. A silent protest at a lecture is a dignified act of moral and political witness. A brief noisy demonstration that ends after a minute registers passionate discontent but preserves academic freedom. Both of course require group discipline. A vocal demonstration that blocks a lecture abandons civility and undermines the purpose of higher education.

A certain portion of the American left now regards civility as a bland form of corporate speak. Or, worse still, as an Orwellian effort to stifle academic freedom. And the far right thrives on hostility and ad hominem attack. Our divided national political culture can hardly be said to encourage anything different. But should a campus try hard to emulate Washington?

Academic freedom does indeed protect both current faculty members and students from institutional reprisals for deplorable speech. But it was never intended to protect people from criticism for what they write and say. Uncivil students and faculty at a university should not be punished. University presidents who urge civility are not trying to stifle dissent or suppress speech. They are trying to make the campus an oasis of sanity. They are trying to urge faculty and students to showcase productive dialogue. That is part of what higher education owes the country. That is part of the cultural and political difference higher education can make.

Civility does not preclude passionate advocacy. It doesn’t preclude devices like irony and humor. Nor does it mean ideas and arguments cannot be strongly expressed and severely criticized. Civil discourse need not be bland. Civility should lead us to treat people with respect, but it doesn’t mean that all arguments or ideas merit respect. Eloquence in the service of conviction does not require abusive rhetoric or personal accusation. It does not require us to claim we know what is in one another’s hearts and to indict people on that basis. It does not require us to demonize our opponents unless we believe they are beyond hope and fundamentally corrupt or evil, a perspective not likely to apply to campus colleagues. Campus speech that harasses, bullies, or intimidates cheapens our communities and diminishes their value.

When administrators urge us to be models of civility they are doing exactly what their job requires. Civility does not mark the boundaries of free speech protection. But it helps describe how we can most often relate to one another productively. Voluntary civility is the best way to conduct difficult debates, but it is not a limit on permissible speech. Faculty members need to teach by example. They need to take the lead in demonstrating what good citizenship entails. Unfortunately, far too many faculty members are doing precisely the opposite.

The Arab/Israeli conflict gives continuing evidence of how inflammatory rhetoric in the Middle East can lead to actual violence. It is thus both sad and ironic to see our campuses conduct debate on the subject as if campus debate amounted to war by other means.