You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Marjorie Darrah, Roxann Humbert and Gay Stewart offer a new, more nuanced way of thinking about levels of first-generation students.

Jen Kim/Inside Higher Ed

The federal government defines a first-generation college student as “an individual both of whose parents did not complete a baccalaureate degree” or “in the case of any individual who regularly resided with and received support from only one parent, an individual whose only such parent did not complete a baccalaureate degree.”

We typically think of a first-generation student as a student who has no immediate family member to provide guidance in enrolling in and navigating the confusing waters of a college experience. We also may assume that these students will be less prepared for the academic challenges of college.

However, after interviewing and surveying students characterized as first generation, it is obvious that the students who fall under this general category come from very different backgrounds.

When talking to one first-generation student, we learned that his grandparent had a Ph.D. and his parents both attended some college or technical school and were professionals in their fields. This student had familial guidance on choosing a college, getting financial assistance, selecting a major and setting up a schedule and also benefited from academic support at home.

Another student we interviewed was from a very rural area; came from a lower socioeconomic background; had little support, financial or otherwise, from anyone in her household; and did not know anyone who had attended college except the teachers in her high school.

We would venture to say these students do not need the same level of support when entering college.

Why Is This Important?

The federal government, colleges and universities have been identifying first-generation students for more than six decades. First-generation college students benefit from federally funded outreach and student success programs. Many colleges and agencies have put resources behind ensuring success of first-generation students. There are national institutions dedicated to the success of first-generation students. However, after all this time, it seems like these students with very different backgrounds are still put in the same large pot and considered to be needing of the same attention.

Better Defining First Generation

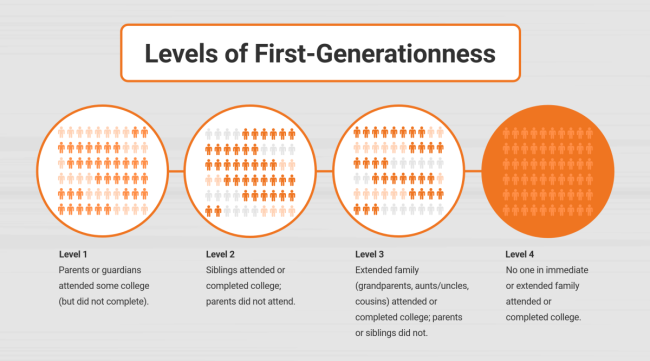

Based on student responses to our interview and survey research, we have defined the following levels of student background. Level 0 students are not considered first-generation students. Levels 1 through Level 4 are all first-generation students but have differing backgrounds.

- Level 0: One or both parents graduated from college (not considered first generation).

- Level 1: Parents or guardians attended some college (but did not complete).

- Level 2: Siblings attended or completed college; parents did not attend.

- Level 3: Extended family (grandparents, aunts/uncles, cousins) attended or completed college; parents or siblings did not.

- Level 4: No one in immediate or extended family attended or completed college.

Does the Level Make a Difference?

Based on the information we received from 76 students at several universities and colleges, we characterized them using the levels above. We classified students at the lowest level they met. For example, if a student had both a parent who attended some college and a sibling who attended or completed college, then they were classified as Level 1.

Of these 76 students, 58 students were considered first generation by the standard definition and 18 were not. Of the 58 first-generation students, there were 33 who were Level 1, 10 Level 2, nine Level 3 and only six Level 4.

We asked students what external and internal factors influenced them to go to college. We also tracked students for at least one year to determine if they persisted.

This study was done as part of a National Science Foundation–funded INCLUDES Alliance and therefore focuses on science, technology, engineering and math majors. We should also note that all students in our study were enrolled in a two-week research experience before their first semester of college and were encouraged to continue to engage in the project throughout their time in college.

We found the external factors that motivated students to attend college were similar, but that teachers, high school classes, friends and extended family members played a larger role for first-generation students than for their non-first-generation peers. The internal motivations for attending college were also similar, but desire for good income was lower for first-generation students (90 percent) versus their continuing-generation peers (100 percent). First-generation students cited career aspirations as a motivating factor at a higher rate (86 percent) than their non-first-generation peers (78 percent). First-generation students also had fewer positive associations with college (71 percent) versus their continuing-generation peers (77 percent).

Since all the students interviewed or surveyed were intending to major in STEM in college, we also asked about the factors, external and internal, that motivated them to enter a STEM major. First, we found that for almost all the categories we investigated, some students had family members who majored or graduated in STEM. Thirty-nine percent of the non-first-generation students and the Level 1 students, respectively, had a family member who majored in STEM, which compares to 10 percent for Level 2 students, 33 percent for Level 3 students and 0 percent for Level 4 students.

High school teachers, classes and STEM clubs were the largest reasons that first-generation students entered STEM. For continuing-generation students, teachers and classes were also important, but parents were far more influential for these students (44 percent) versus for their first-generation peers (24 percent). First-generation students also had fewer positive associations with STEM (62 percent) versus their non-first-generation peers (72 percent).

The students in our study entered college during the 2018 to 2021 fall semesters. For the 53 students enrolled in years 2018 to 2020, we can report on persistence in a STEM major till the end of 2020, based on their first-generation levels. Persistence was 93 percent among first-generation Level 1 students, 80 percent among Level 2, 83 percent among Level 3 students and 75 percent among Level 4 students. We will continue to track persistence over the next four years for these students.

Although this is a small set of data and the percentages presented are descriptive statistics at this point, we feel the idea of first-generation levels warrants more investigation.

What Do We Suggest?

At our institution, we have decided to add a question to identify first-generation level on a widely used survey given to most students in first-year STEM classes. We also track persistence of STEM majors and can determine from this if level makes a difference in overall persistence and success.

Based on our initial research, it seems the first-generation Level 1 students (parents attended some college) seem to be able to keep pace with their non-first-generation peers. However, we believe that first-generation Level 4 students, and possibly Levels 2 and 3, are particularly vulnerable and could use more assistance. There are not nearly as many of these students as total first-generation students, and they are the ones who would most greatly benefit from a targeted intervention, such as peer mentoring or special advising to navigate administrative tasks, as well as financial counseling. It is not that the other first-generation students, or even continuing-generation students, do not need help, but they may not need as much.