You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The Memphis College of Art is winding down operations and plans to close after May 2020.

Memphis College of Art

It’s no secret that private, nonprofit art colleges have been showing cracks in recent years.

In just the last several months, the Oregon College of Art and Craft explored mergers with two different institutions, only to have talks fall apart. The University of New Haven decided in August to end degree-granting programs at Lyme Academy, whose academic programs it took over under an agreement five years ago. Last week the Cornish College of the Arts announced it is cutting tuition by 20 percent in the 2019-20 academic year, adopting a tuition-reset strategy that’s frequently been deployed by institutions seeking a shot of attention to help boost enrollment. And the New Hampshire Institute of Art is in the midst of merging into New England College.

A bit further in the past, the Memphis College of Art announced in October 2017 that it would be closing and has laid out plans to shut down after graduating the last of its students in May 2020. The School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston reached an agreement to have its educational operations acquired by Tufts University in 2016. The Art Institute of Boston, which merged with Lesley University in 1998, moved from Boston to Cambridge to join its sister colleges in 2015, taking on the new name of the Lesley University College of Art + Design along the way.

Also in 2015, the Montserrat College of Art explored merging into Salem State University, but the two sides ultimately ruled out the move. That decision came the year after George Washington University decided to acquire the Corcoran College of Art + Design in Washington.

Those cases alone mean that about a fifth of the 43 institutions that were members of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design as of the start of 2014 have attempted to merge, closed, relocated or drastically changed their tuition structure in the last five years.

They’ve done so while facing some pressures unique to art schools, according to leaders in the sector. Curricular changes make it more difficult for some students to take classes before they graduate from high school, meaning art schools must work harder to reach prospective students at an early age. Meanwhile, art schools remain capital-intensive operations to run, as supplies, equipment, small class sizes and generous faculty-to-student ratios keep expenses high.

But art schools have also been under pressures that cut across the higher education landscape and are bearing down on many liberal arts colleges. Population and demographic shifts are changing where high schoolers are graduating in the greatest numbers, who those students are, what they can pay and what they value in a college education. And as the cost of providing students with a good education rises annually, many small institutions struggle to keep costs in line without the benefits of efficiencies of scale.

“I often say we are a microcosm of the higher ed environment,” said Deborah Obalil, president and executive director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design. “There are challenges in particular to the very small, under-500-student institutions. I think that is applicable across all of higher ed, because the challenges they face are not special to them because they are art and design institutions. It is really about their scale.”

The art school market is bifurcating based on institution size. Although enrollment remains strong across a core group of institutions, those with more than 500 students are much more likely to see their fortunes rise than are those with smaller enrollments, observers say. Some of the best known larger institutions, like the Rhode Island School of Design and California Institute of the Arts, are considered to be doing quite well, even though they are not huge, with reported enrollments of about 2,500 and 1,500, respectively.

The pressures playing out at colleges of art may resonate particularly strongly at this moment in time because some struggling private liberal arts colleges have been taking steps that could make them resemble art schools. Strategists sometimes counsel endangered liberal arts colleges to find an area of focus or a special niche to fill -- paralleling art schools, which arguably embody the ideal of specialization.

Now, that ideal has been called into question after Green Mountain College, which had carved out a niche in environmental liberal arts, decided last month to close in the face of financial challenges.

Backers of art schools say the personalized education they provide and creative thinking they inspire are more important than ever in a world where students from all disciplines will need to be able to adapt their skills to a fast-changing workplace. But as pressures play out in the market, it’s become increasingly clear that some institutions have been able to continue to attract students and pay their bills, while others have fallen behind.

It’s also growing more and more clear that small institutions with negligible endowments and other disadvantages can’t always count on clever strategy alone to save them -- whether that strategy is merger, debt reorganization or specialization. Art school presidents think sound decisions can still strengthen most institutions, but they need to be deployed with increasing levels of sophistication.

Specialty institutions can remain viable if they examine their business models and revenue streams, said Kurt T. Steinberg, president of the Montserrat College of Art and a former executive vice president at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design who spent a year as acting president there. Only they must be making the right choices quickly “and defining who they are and why they have a competitive advantage.”

How Strong Is Enrollment?

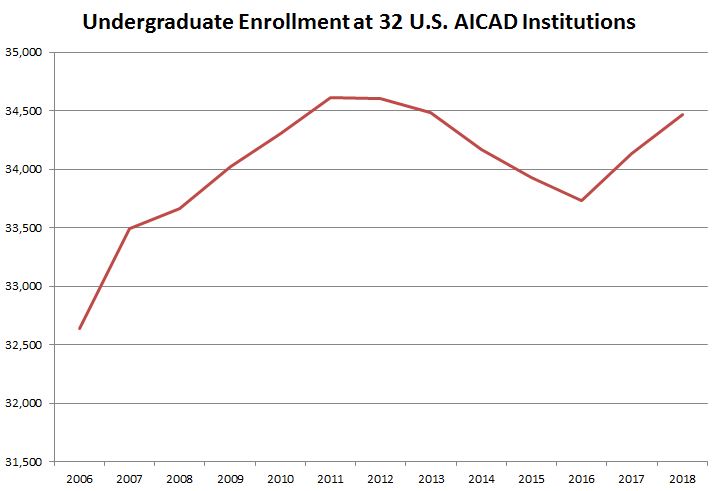

By some measures, art schools are enrolling more students than they did a decade ago.

As a group, the institutions in the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design enrolled 34,466 undergraduates in 2018. That’s an increase of 2.4 percent from 2008, which would be roughly in line with projections showing very little growth in the number of high school graduates over the same period.

But the data only include 32 institutions that are based in the United States, fully independent and still enrolling new students. They don’t include small institutions that merged with larger institutions in recent years, nor do they include closing institutions, like the Memphis College of Art.

Enrollment data measured at the institution level can’t include closures and mergers, according to the association’s assistant director in charge of research services, Joanne Kersh. Students in a merging or closing institution don’t disappear, but the association can’t account for them, so it provided data only on those institutions that remain open and independent.

“Our institutions that have closed were very small, and had seen declining enrollments for years, and generally they do teach-outs as they prepare to close their doors,” Kersh wrote in an email. “Students enrolled at the merger schools, well, I think they mostly stay where they are, or the enrollment change is gradual. I've even seen enrollments rise after a merger, as the previously small independent school now has more resources available. But, as we can't account for the movement of students between schools, I think a cleaner look at stable institutions over time offers the most accurate perspective.”

While that may be the case, it also arguably means the statistics screen out institutions that have been forced to go through major changes -- and they are likely to be the weakest, experiencing the greatest enrollment declines.

With a few exceptions, most of the association’s member institutions that enroll more than 500 students have seen enrollment rebound in the last few years, while those with fewer than 500 have seen it fall, Obalil said. It’s not clear whether 500 is a firm dividing line or just happens to be the current level at which institutional fortunes are diverging.

“In terms of the schools that have actually closed or merged, each picture is unique, to some degree,” Obalil said. “What commonalities I’ve seen often line up, again, with size and the inability to scale.”

Such institutions have failed to differentiate themselves from the rest of the marketplace, or they have not reconsidered their curricula in five, 10 or even 20 years, she added. Some can’t add another program because they are too small to afford it, and others are faced with a high level of debt.

Art schools don’t tend to have large endowments, so a combination of high debt and a failure to attract enough students can be a fatal combination.

Closing or Clawing Back

Such a combination helped to bring down the Memphis College of Art. The college saw its undergraduate enrollment fall from 362 in 2009 to 338 in 2016, according to statistics in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. By 2017, enrollment had fallen to 278.

The college struggled to attract students in the postrecession era, said its president, Laura Hine. Students and families were questioning the value of a four-year art degree and emphasizing job skills even as the college grappled with its identity.

“There was a sense that we’re a fine arts school, and we can’t abandon our history and our roots,” Hine said.

Looking back, Hine thinks the college could have built sustainable programs while balancing the need to stay true to the fine arts with new investments. It could have used its animation program, which is the only one of its kind in the region and was in demand, as a foundation.

As it faced new challenges related to enrollment and programming, the college’s past decisions caught up to it. The college was struggling with debt from real estate purchases made in the past, Hine said. Although leaders attempted to reduce debt levels and secure lower interest rates, they couldn’t do enough.

In October 2017, the college announced that its board decided to stop recruiting new students, dissolve the institution’s assets and teach-out existing students. At the time, it cited “declining enrollment, overwhelming real estate debt, and no viable long-term plan for financial sustainability.”

Without a large endowment to draw upon, the college had been relying on revenue from enrollment and the philanthropic community, which had been exceptionally generous, Hine said. Major donors were tapping out, though.

Soon after announcing its plans to close, the college staged a transfer fair, encouraging new freshmen to enroll in another institution, Hine said. It moved to teach-out remaining students, which has been a challenge because tuition revenue shrinks as students leave and new classes aren’t recruited. The college expects to graduate its last students in May 2020.

Larger colleges with more diversified funding from states or other sources might be better positioned to survive or thrive in the face of pressures, Hine said. Some college presidents worry that too many art schools being affiliated with states could diminish students’ freedoms, however. State funding brings in political considerations that budding artists don’t always appreciate.

Hine also worries about the students who are “born artists” and would have enrolled at the Memphis College of Art, were it not closing.

“We were attracting and have attracted kids -- a lot of kids -- that were coming out of poverty,” Hine said. “Some of our kids live with their family members. They can’t up and move to Sarasota, Fla. They don’t have the capacity to do that and the support to do that.”

The experience leaves Hine, who has worked in work-force development, worried about the future of art schools and education more generally.

“The disparity between people’s ability to pay for college now and what it used to be, I think, is growing increasingly greater,” she said. “And in a situation where colleges and universities today have a lot of costs -- technology, security, Title IX compliance, accreditation burdens that have become more and more onerous on the cost side -- and you don’t have it being offset by this burgeoning middle class or upper middle class that can send their kids to school, I think it’s a crisis brewing.”

Other colleges are still fighting to grow and improve their fortunes. At the end of January, the Cornish College of the Arts announced that it will reset its tuition from $40,442 this year to $32,160 for all new and returning students in the 2019-20 academic year. In doing so, it believes it is the first fine arts school in the country to put a tuition reset in place.

The move comes after Cornish, a college located in Seattle that typically enrolls about 700 students and offers a bachelor of fine arts, bachelor of music and postbaccalaureate artist diploma in early music, compared itself to competitors. It found that it was attracting low-income students who receive Pell Grants or state grants, as well as students who could afford to pay $40,000 in annual tuition. But it was struggling to enroll those from middle-income families, according to Raymond Tymas-Jones, the college’s president.

Cornish does not have any graduate programs and enrolls few international students, Tymas-Jones said. About half of its students come from the Pacific Northwest. Therefore, a price point that middle-income families can afford is critical, and will hopefully improve the college’s enrollment prospects.

“We really believe that with the reset, we will be competitive,” Tymas-Jones said.

Cornish’s tuition discount rate was 39 percent, Tymas-Jones said. It’s expected to drop to 23 percent with the reset, a change that is in line with many other colleges making such moves, although both rates are relatively low by private college standards.

Recruiting more students in today’s market requires sophistication, presidents said. Students who might consider an art school go to their art teachers for advice first, not their guidance counselors, said Steinberg, president of the Montserrat College of Art.

Reaching students also means telling them as early as middle school that art school is a viable option, Steinberg said. With more and more being packed into high school curricula, many students are being forced to choose between taking classes in the visual arts and other subjects, like music, as freshmen.

Steinberg has seen remarkable changes in enrollment during his career as students’ interests evolve. When he left the Massachusetts College of Art and Design last year, 70 percent of students were enrolled in design programs and 30 percent were in fine arts, he said. A dozen years earlier, when he arrived at the institution, the split was 50-50.

“The fine arts-only institutions, those institutions that didn’t add design to their offerings, are the ones that are suffering early,” Steinberg said.

Unfortunately, more programs means spending more money, particularly in the world of art schools. Computers have to be replaced frequently, and software is constantly updated. Meanwhile, institutions must maintain what amounts to industrial facilities while keeping class sizes small.

“The amount of airflow that a print-making shop has to have is huge and is equivalent to exhaust systems that might be on large pieces of equipment in a factory,” Steinberg said. “In a hot shop for glass, you can only have that class be a certain size. Otherwise, someone is going to get hurt.”

Is massive growth or merger the only way a small struggling art college can stay on top of it all? Not if they’re making the right moves and the hard choices, presidents say. When Montserrat failed to merge with Salem State, it forced a period of soul-searching and decision making that has allowed the institution to strengthen itself after an initial hit, even as it enrolls only 370 or so students, said those who watched the situation.

Steinberg, who joined the college after the merger discussions were long since over, said he hopes to grow Montserrat to have 400 or 500 students. That will allow it to have enough scale to stay strong while also keeping its founding vision of being a small institution.

“I don’t want to lose the idea that the differentiation in the kind of education we have is important,” Steinberg said. “Only having 10,000-student institutions is not, necessarily, I think, a good idea.”

Back on the West Coast, the Pacific Northwest College of Art (at right), in Portland, Ore., wants to grow to 1,000 students over the next several years. It has about 600 today, said its president, Don Tuski.

Back on the West Coast, the Pacific Northwest College of Art (at right), in Portland, Ore., wants to grow to 1,000 students over the next several years. It has about 600 today, said its president, Don Tuski.

Last fall, the college had been in merger talks with the 140-student Oregon College of Art and Craft, which is also in Portland. The two sides called off the deal, and Oregon College of Art and Craft went on to discuss merging into Portland State University. Those talks died at the end of the month, with The Oregonian reporting that the Oregon College of Art and Craft would continue examining opportunities for partnerships and revenue streams in the face of financial struggles.

Tuski didn’t go into detail on the merger discussions, other than to say that it didn’t make sense from a curricular standpoint. The Oregon College of Art and Craft did not return requests for interview by the deadline for this story.

The Pacific Northwest College of Art is trying to recruit students by articulating a strong value proposition, Tuski said. Going from studio to gallery is still a pathway, but it wants its students to be able to make a living in multiple ways, including through entrepreneurship.

Faculty members in client-based fields, like illustration and graphic design, already think that way, he said. Others have been receptive, especially when the discussion is raised in a broader conversation about student debt and the fact that not all students can go on to get M.F.A.s and become art professors.

“We still want students to do great, experimental, edgy artwork,” Tuski said. “But if they learn to apply that creativity in multiple ways, that’s what society wants and needs, and that’s why I think art schools, if they get their business models together, can be leaders in society.”

It’s a compelling pitch, although other art schools have made it. A generic liberal arts college has also likely made that argument to students.

Yet to be seen is whether it will work for the Pacific Northwest College of Art -- or any other art school seeking to hit enrollment targets in a competitive market.

If he is worried that other specialized institutions have tried similar strategies and failed, Tuski isn’t showing it.

“Part of being distinctive is also doing something better than other people -- doing something different but also doing something everybody else is doing, but doing it better,” he said.