You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Colleges and universities had to react quickly to COVID-19, including with respect to the faculty. A year into the pandemic, it’s time to pause and assess the impact that it has had on professors -- especially on women, who face disproportionately more caregiving work at home and corresponding blows to their productivity. Then it’s time to move forward more thoughtfully, guided by policies that center equity and intersectionality.

This is the essential message of a massive new consensus report on COVID-19 and the careers of women in academic sciences, engineering and medicine from the National Academy of Sciences.

“We as a community in academia, we have to pay attention,” said Eve Higginbotham, chair of the report committee and vice dean of inclusion and diversity and a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania. “This is an issue we have to be intentional about, as we are at risk of losing a significant portion of valued members of our community.”

As dire as some of the report’s findings are, Higginbotham and other committee members who spoke at a news conference Tuesday said their work -- and the general moment -- present opportunity.

Reshma Jagsi, Newman Family Professor and deputy chair of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan, said, “The most important takeaway of this report is that this pandemic has handed us a whole boatload of lemons that we can squeeze to make lemonade.”

As an academic physician, Jagsi continued, “I can’t help myself -- I see everything as an opportunity for continuous quality improvement and in the classic framework of plan, do, study, act.” As of right now, she said, the next step is to share the report far and wide and, and then “each institution needs to make a commitment to trying something, do something.”

More Than an Individual Problem

Instead of straightforward recommendations, the report proposes a number serious questions for future research. Higginbotham urged institutions to fund and explore them -- in the hope these research efforts may lead to lasting solutions.

“Certainly it’s a matter of actually getting institutions to think about their role and shifting focus from individual personal agency,” she said. “I think we’ve all heard the talks about resiliency … The onus now is more on institutions to actually come up with infrastructure changes to help support women in STEM.”

Questions for further research include:

- What are examples of institutional changes adopted during COVID-19 that have the potential to reduce systemic barriers historically faced by academic women in STEM, specifically women of color and other marginalized women? How might positive institutional responses be leveraged to create a more resilient and responsive higher education ecosystem?

- How might insights gained about work-life boundaries during the pandemic inform how institutions offer faculty members support, such as reductions in workload, on-site childcare and flexible working options?

- How can institutions maximize the benefits of digitization observed over the last year to continue supporting women, especially marginalized women, by increasing accessibility, collaborations, mentorship and learning?

- What specific aspects of different leadership models led to effective strategies to advance women in STEM, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How might insights gained about mental health during COVID-19 be used to inform preparedness for future disruptions?

Most questions relate to the themes of five separate papers the committee commissioned from colleagues to inform its deliberations. These papers address the impact of COVID-19 on tenure clocks, evaluation of productivity and career trajectories; boundary management, work-life integrations and household labor; collaboration, mentorship and sponsorship, and the role of networks and professional organizations; academic leadership and decision making; and mental health and well-being of women in STEM.

‘There Are No Boundaries’

In addition to these five papers, the report is informed by an original survey of 733 tenured or tenure-track professors and 170 non-tenure-track professors, fielded in October. The committee asked women how their lives had been changed -- good and bad -- in the six months prior. All respondents were working at home more than they had before, but women with children at home were especially cloistered, often more than they wanted to be. All respondents reported losing work-life boundary control -- mothers most of all. As one professor said, “My son had a meltdown five minutes before my Zoom class was supposed to start.”

Another professor reported being constantly interrupted on Zoom calls by her own small daughter, sometimes about potty talk. Another said life was “happening simultaneously. I am working, and I am caring for my 1-year-old. I am answering emails while making dinner. I am recording lectures while he naps. There are no boundaries, as everything happens at the same time and in the same space.”

Respondents reported negative effects on their productivity, including increased workload (27 percent of the sample), decreased effectiveness (25 percent), poorer social interactions with peers and students (20 percent), and adverse effects on teaching and research (20 percent). One professor reported feeling “like my workload has increased by 50 percent. I’m not able to keep up. I am worn out and tired of having to constantly apologize for being late.” Other concerns were about decreasing institutional resources and support, such as pay cuts.

All of this chipped away at respondents’ well-being, with two-thirds saying theirs had declined. One-quarter reported a hit to their psychological well-being in particular. Six percent said the pandemic was causing a lack of sleep.

One assistant professor with children described being “constantly stressed that the lack of lab productivity will cause me to not get tenure. I lose sleep over it.”

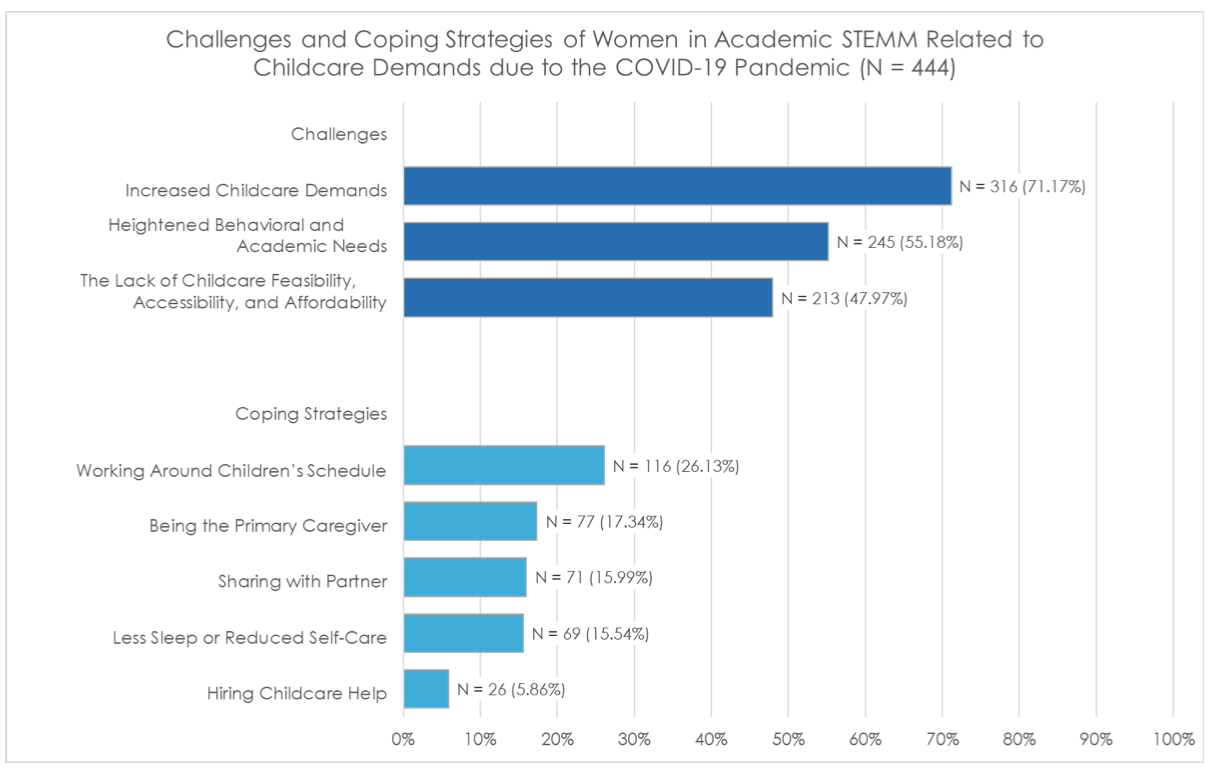

Astonishingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, given prior research, 90 percent of these female faculty members said they were handling a majority of their children’s school and childcare demands. Only 9 percent of women reported sharing childcare demands equally with their spouse. Just 3 percent said they had help from a babysitter, nanny or tutor during COVID-19, with others citing concerns about health and safety, accessibility, and cost.

Overseeing children’s schooling at home was major challenge for many respondents.

“I am on the verge of a breakdown,” one associate professor said. “I have three children doing virtual schooling full-time who need my attention throughout the day; they all have different break schedules and seemingly interrupt me every 10 minutes. I want them to learn and thrive and I try to make these difficult circumstances for them as positive as possible, which means giving more of myself and my time to them.” She continued, “I try to wake up before them and work after they sleep, but this is hard given they wake up at 7 a.m. for school and don’t go to bed early (they are 13, 11 and 8). There are sports/activities, dinner, homework/reading, etc. All the things that keep my evenings busy when they were in school, but now it is all day.”

Some 13 percent of respondents did mention positive effects of social distancing on family life, such as enjoying more family time together, no commutes and not having to dress up for work. But some parents also reported worrying about their children’s mental health and behavior changes during prolonged isolation.

Some 13 percent of respondents did mention positive effects of social distancing on family life, such as enjoying more family time together, no commutes and not having to dress up for work. But some parents also reported worrying about their children’s mental health and behavior changes during prolonged isolation.

Increased eldercare for parents, or not being able to see them, was a concern for a significant subset of female academics surveyed, as well.

Respondents adopted various boundary-management mechanisms to cope, but often their increased caring and workloads led to less self-care and sleep.

Institutional Responses Lacking

Women said that institutions most often responded to the pandemic by offering them the option to work remotely, stopping tenure clocks and allowing them to choose their mode of teaching -- online, off or both. Some respondents said their institutions didn’t have clear plans and policies to help their professors teach remotely, however. Few institutions provided any support with childcare needs. And instead of stopping tenure clocks, many professors said they needed their colleges and universities to clearly acknowledge that the pandemic, however long it lasts, is going to result in lower faculty productivity.

Non-tenure-track professors in particular were worried about the pandemic’s negative effect on their teaching. They reported increased workloads and stress resulting from “technology problems, having to offer multiple formats to students, developing new content, and a lack of clear directions from administrators on decisions that could help planning,” according to the report.

One lecturer with eldercare responsibilities said, for instance, that “Early in the pandemic (March and April), there was so much communication (much of it contradictory) from department, college, and university level admin that we were jerked every which way almost every day. Admin seemed to think you could totally redesign your course on a dime in the middle of the semester, and sent us ads from third-party vendors, as well as constantly changing policy edicts and requests for information.”

The lecturer reported working “10-12 hours per day, seven days per week,” with “very unhappy students. The stress was unbearable, and by June I was in ICU with a stroke. Thankfully I have recovered sufficiently to keep working. But I fault the university for the amount of stress they caused.”

Instead of tenure and promotion concerns, many non-tenure-track professors said they wanted extra teaching support for grading, technology and converting courses to virtual formats.

The report includes some interesting findings on institutional responses to COVID-19, courtesy of contributor Adrianna Kezar, director of the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the University of Southern California.

Citing data from the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education at Harvard University, Kezar said that faculty members tended to give their administrators positive ratings early on in the pandemic, due to their quick action on campus shutdowns. But faculty members were less approving going into the fall, registering “concerns of being left out of decision-making processes for months, particularly on decisions that shape domains of teaching and learning, but also more broadly to significant decisions about program closures, finances and layoffs.”

This is not the case everywhere. Kezar praised the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, for instance, for capitalizing on existing diversity, equity and inclusion staff and other key practices to introduce a meaningful set of COVID-19-related faculty policy changes. Those shifts involved tenure, promotion and review policies; a new evaluation process; adapting teaching expectations and suspending teaching evaluations; and establishing emergency funds for childcare and technology. The university also moved forward with salary increases even when promotions were delayed.

Kezar said that college and university leaders can “make decisions, govern, and be accountable in ways that are gender-inclusive and help to eradicate growing equity gaps.” Their strategies for doing so may involve drawing on the expertise of existing diversity, equity and inclusion staff, as seen at UMass Amherst. Other promising strategies include creating new structures to address decision-making needs, Kezar said, and “altering existing processes to include more voices in decision-making.”

Recommending shared governance, equity mindedness and best practices in crisis leadership, Kezar said a few campuses “have begun to think about the long-term implications of the COVID-19 pandemic and to recommend strategies to address this issue, such as revising strategic plans aimed at ameliorating equity gaps … While there is evidence from the first nine months of the COVID-19 pandemic of worsening gender inequalities, there are also existing strategies available for reversing these trends.”

Other Major Findings

The consensus committee report’s other major findings -- informed by the commissioned papers beyond Kezar’s and the survey data, are:

- Women’s representation in STEM was increasing leading up to COVID-19, but women’s representation in leadership tended to be higher at institutions with “less prestige” and fewer resources. And “while promising and encouraging,” women’s progress in STEM “is fragile and prone to setbacks especially in times of crisis.”

- Social crises and COVID-19-related disruptions have the potential to exacerbate mental health conditions such as insomnia, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress.

- Structural racism is an “omnipresent stressor” for women of color, who already feel particularly isolated in many fields and disciplines. Equity interventions must therefore consider women across various identities.

- While some research indicates consistency in publications authored by women in specific STEM fields, in 2020, multiple other measures of productivity suggest that COVID-19 disruptions have disproportionately affected women compared with men.

- Work-life boundaries have been blurred and women in academic STEM are experiencing increased workload, decreased productivity, changes in interactions and difficulties from remote work.

- Technology has allowed for collaborations to continue and in some cases has facilitated the increased participation of women and underrepresented groups. Yet preliminary indicators also show gendered impacts on science and scientific collaborations during 2020. Some collaborations cannot happen online, and some women struggle to find time to engage synchronously with collaborators, even online.

- Transitioning conferences to virtual platforms has been both good and bad for women, offering lower attendance costs and more access to content as well as “over-flexibility” and new opportunities for bias.

- On mental health, the report says the pandemic has limited women’s social support systems -- something that’s particularly worrisome for women “already isolated within their specific fields or disciplines.” For women in the health professions, major mental health factors during 2020 included unpredictability in clinical work, evolving clinical and leadership roles, the “psychological demands of unremitting and stressful work, and heightened health risks to family and self.”

Underscoring the committee’s message about moving intentionally and inclusively going forward, Jagsi said during the news conference, “We’ve been in such a panic, and this has been a real challenge, but I think we can finally come up for air and actually reflect on things that we’ve known for a long time. And slow down a little bit and get things right. Because it’s going to be a mess to undo things that we’ve done hastily and wrong.”